Tripping

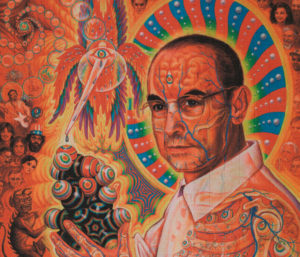

75 years ago, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann experienced the first LSD trip in history. LSD has been changing our view of the world ever since.

On the afternoon of 16 April 1943, Albert Hofmann was looking for a circulatory stimulant. In the lab at Sandoz AG in Basel, he synthesised lysergic acid diethylamide – LSD for short. Somehow, the substance entered his body. Hofmann experienced a “remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness”, broke off his work and went home. He reported to his supervisor:

“At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterised by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours. After some two hours this condition faded away.”

Albert Hofmann in his laboratory, © Novartis company archives

Hofmann’s intoxication was a puzzle for the chemists at Sandoz AG. No substance was known to produce such tremendous effects in such small quantities. So three days later, Hofmann took LSD again, this time deliberately as an experiment, using what he believed to be the minimum dose of 250 micrograms. But even this small amount led to “dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of paralysis, desire to laugh,” as Hofmann noted in the laboratory journal. He broke off the experiment and noted only: “Home by bicycle.”

It was a bit crazy: the Red Army was marching into Stalingrad. In the USA they were starting to enrich plutonium for the atomic bomb. In Basel, Albert Hofmann went on the first LSD trip in history and rode his bike home. In commemoration of this trip, 19 April is celebrated annually as Bicycle Day, with appropriate depictions of Hofmann on his bike.

Blotting paper with bicycle motif, as commonly used in the illegal trading of LSD. Photo: Daniel Allemann, Kantonsapothekeramt Bern

Hofmann’s findings can be traced back to Arthur Stoll. At Sandoz AG Stoll had been working with ergot – a fungus known as a poison and a medicinal substance that mainly affects rye seed heads – since the 1920s. Stoll had derived ergotamine from ergot. As a result, the company was cultivating ergot on a large scale. In the Emmental and elsewhere, farmers and day-labourers were inoculating their rye crops with the fungus. But did ergot hold other medicinal properties as well? That’s what Hofmann had set out to discover when he stumbled across the psychedelic effect of LSD.

Rye seed heads infested with ergot, cultivated by Sandoz AG, Institute of Medical History, University of Bern, estate of Albert Hofmann

Gun inoculation of rye seed heads with ergot, 1943, © Novartis company archives

Arthur Stoll’s son Werner worked as a psychiatrist at the Burghölzli clinic in Zurich – a short distance from the laboratory. Not long after Werner Stoll’s initial experiments in the 1940s, LSD started to be widely used as an experimental substance. After 1950, Sandoz AG marketed the substance for research purposes worldwide under the brand name “Delysid”.

From 1950 onwards, LSD became part of a hype: a plethora of new drugs raising hopes that chemicals could be used to regulate the psyche. The experiments with LSD spread in ever-widening circles. The psychologist Timothy Leary and the author Ken Kesey also came into contact with the substance. For them, LSD was not a medicine, but a saviour. They preached the virtues of the drug and encouraged its use, finding an eager audience in the emerging hippie movement.

Around 1960, a veritable acid subculture emerged. Artists like Yayoi Kusama, authors like Allen Ginsberg and musicians like Jefferson Airplane saw the LSD trip as a source of inspiration and spiritual liberation. In Switzerland too, art discovered LSD: the author and psychiatrist Walter Vogt, the band Brainticket and the artist Serge Stauffer are just three examples in a long list of creative types who used acid trips for their work.

Brainticket, Cottonwoodhill, 1971. Video: YouTube

But the party didn’t last long: in the “hippie year” of 1968, ironically, Switzerland issued the first partial ban on LSD. More stringent requirements for medicines, a growing awareness of the health risks and lack of economic viability saw LSD vanish into illegality.

While the ban didn’t prevent the use of LSD, it created a stigma around it and made it less visible. This didn’t change until the turn of the millennium. The first new scientific experiments with LSD began at the universities of Zurich and Basel. In Solothurn, psychiatrist Peter Gasser received the first special approval for a study with patients. After almost 30 years, LSD had reappeared.

Interview with Peter Gasser (in German), 2018. Video: Swiss National Library

Today, a more differentiated approach to the substance is emerging. LSD is neither a saviour nor the devil’s brew. Rather, it’s a substance with health risks and medical potential. And a rich history.

LSD – A problem child turns 75

Swiss National Library Bern

07.09.18 - 11.01.19

In the exhibition LSD – A problem child turns 75, the National Library in Bern tells the story of LSD. Based on Albert Hofmann’s book LSD: my problem child, the exhibition traces the journey of the substance from field to laboratory and from clinic to popular culture. Extracts from the correspondence between Albert Hofmann and Walter Vogt, and around 20 works by Serge Stauffer, are also on display.

Imagine 68 – The Spectacle of the Revolution

National Museum Zurich

14.09.18 - 20.01.19

Following the successful exhibitions “1900–1914. Foray into Happiness” (2014) and “Dada Universal” (2016), in 2018 Stefan Zweifel and Juri Steiner present their perspective of the generation of ‘68. The collage of the two guest curators, featuring objects, videos, photos, music and works of art, turns the atmosphere of 1968 into a multisensory experience. The exhibition takes a comprehensive look at this cultural time period, letting visitors float through Warhol’s Silver Clouds into a world of fantasies past