The Romandy/German peace divide

The outbreak of World War I split the Swiss Peace Society between the German-speaking and the Romandy, or French-speaking, sections. The conflict in which these two linguistic regions became embroiled, referred to as the ‘divide’, presented Switzerland with a crucial internal test.

Even before the war, the German-speaking part of Switzerland had aligned itself with its northern neighbour, with many intellectuals spending some semesters of their studies at German universities. In the west, Romandy, the largely French-speaking area of the country, its politicians and cultural figures were strongly aligned with France. After the outbreak of war, this attitude hardened even further, and the rift between these two segments of the country deepened to a conflict that jeopardised the very fabric of the nation.

Violation of Belgian neutrality

The violation of Belgium’s neutrality by German troops led to major upheavals among the pacifists, with the leading figures in the Swiss Peace Society papering over these cracks only with great difficulty. The appeals by German-speaking sections of the movement, calling for the country’s Federal Council to mediate a peace deal, were met with criticism by most of the French-speaking sections. Germany’s breach of international law had shown once again that in order to establish world peace, the Prussian military machine must be crushed. A meeting convened in January 1915 at the International Peace Bureau in Bern resulted in the breakdown of the conciliation efforts between the pacifists, with disagreements over the Belgian issue a major sticking point. While the President of the Swiss Peace Society, Lucerne councillor Franz Bucher-Heller, voted for a resolution from the Austro-German camp, all the French-speaking members supported the views of the pacifists from the Entente Powers. There could be no talk of a unified front within the Swiss peace movement. The satirical magazine Nebelspalter represented ‘divided Switzerland’ symbolically with a Jass card on which the French-speaking and German-speaking parts of the country, each with its own particular cultural characteristics, were facing off against one another.

Franz Bucher-Heller. Gemeinnützige Gesellschaft der Stadt Luzern

‘Divided Switzerland’ in an illustration in the Nebelspalter magazine. Nebelspalter Verlag

War-weariness and peace initiatives

By 1916, it was clear there was no longer any question of rapid military victories. Contrary to the expectations of Falkenhayn, Germany’s Chief of General Staff, the fighting had not gone in the Germans’ favour in the bloody struggle for Verdun, nor was victory achieved by the soldiers of the Entente, under no less appalling losses, in the Battle of the Somme. On all sides, there was deep exhaustion, compounded by food shortages.

In these conditions, peace initiatives received a boost: the ‘Ford Mission’ supported by the American industrialist Henry Ford and the ‘Stockholm Conference of Neutrals’ endeavoured to set peace talks in motion. Peace demonstrations held in Switzerland in May 1916 were well attended; people were clearly happy, after a year and a half of war, to publicly voice their opposition to the hostilities. On 14 May 1916, Franz Bucher-Heller, together with the inter-parliamentarian Joseph A. Scherrer-Füllemann, spoke at a peace rally in front of the International Museum of War and Peace in Lucerne. They mobilised an audience of 1,000, jointly calling on the Federal Council to intervene and sue for peace. This move was met with serious reservations among the Romandy sections because, with the way things were going on the fronts, peace initiatives would be to the advantage primarily of the Central Powers. When St Gallen National Council member Scherrer-Füllemann appealed once again, in the parliamentary session of 28 March 1917, for the Federal Council to intervene to negotiate a peace, the President of the Geneva section, Louis Favre, explicitly accused him of being in the service of German propaganda.

Food prices rose as the war dragged on. For military staff, Soldatenstuben (soldier’s barrack rooms) were an affordable alternative to the usual inns and the often unpalatable army rations. Here, the Soldatenstube in Vira, Ticino. Swiss Federal Archives

The International Museum of War and Peace in Lucerne. City Archives, City of Lucerne

The Grimm-Hoffmann affair

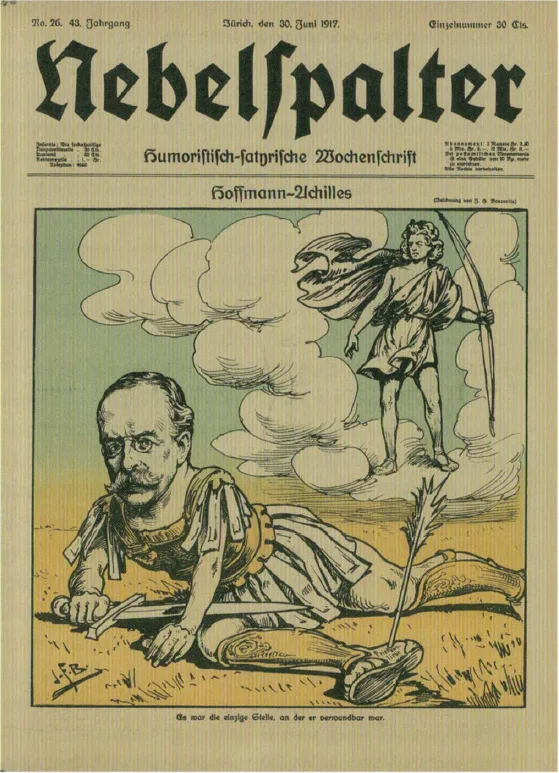

The essentially passive stance of the Swiss Federal Council with regard to peace negotiations contrasted sharply, in the late spring of 1917, with the actions of a member of the government. When social democrat Federal Councillor Robert Grimm decided to work towards achieving a separate peace between Germany and Russia, he had the backing of Arthur Hoffmann, the head of the Political Department. However, Hoffmann was acting without the approval of his government colleagues. After his machinations became known to the public and Switzerland was suspected of partisanship towards Germany, Hoffmann resigned. His motives are debated to this day. The Nebelspalter presented him as a fallen Achilles, with the word ‘Friedensliebe’ (love of peace) written across his one vulnerable heel. His actions sparked protests in French-speaking Switzerland. This ‘divide’ in judging Hoffmann’s motives also ran through the Swiss Peace Society: while some Swiss-German sections tried to organise solidarity rallies in his support, the Swiss-French branded Hoffmann’s actions a gross violation of neutrality and an effort in favour of the Central Powers.

Hoffmann’s depiction as fallen Achilles in the Nebelspalter. Nebelspalter Verlag