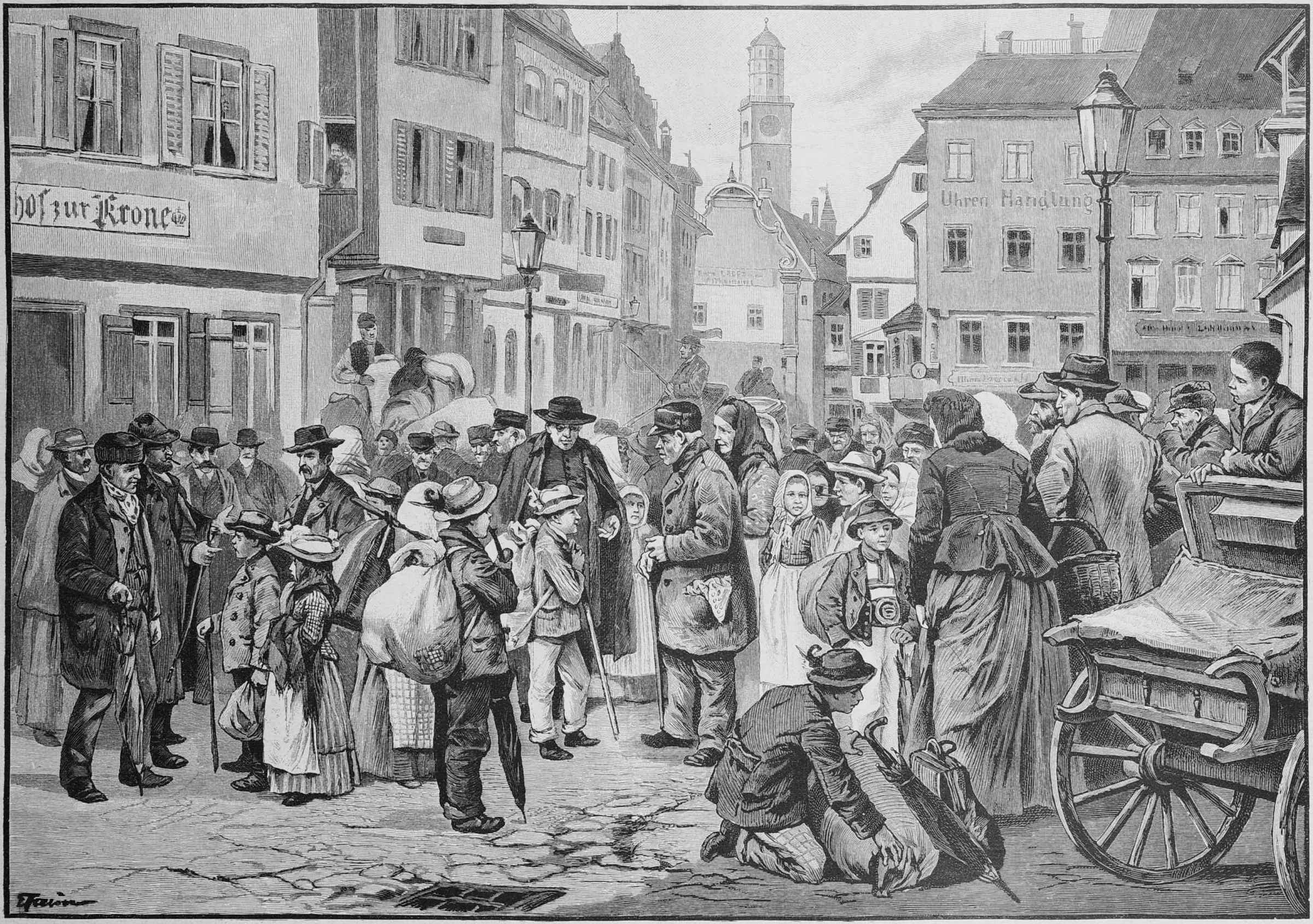

A dark chapter in Switzerland’s history

Abused, not cared for – these few words sum up the fate of countless children, adolescents and adults in Switzerland up into the 1970s. Under the title ‘Vom Glück vergessen’ (Forgotten by happiness), the Rätisches Museum Chur vividly brings to life for its audience the reality of ‘enforced welfare measures’.

00.00

‘I’ve been treated like a package.’ How indentured child labourer Ruedi Hofer* (born in 1943) was shunted from one place to another and suffered a serious injury. Interview: Tanja Rietmann, in Swiss German. Rätisches Museum