nBurg Zug Museum

From Buchenwald to the Zugerberg

“Gezeichnet” (“Drawn”) is the title of an exhibition of more than 150 drawings done by the “Buchenwald children”, which have never before been shown in public, at the Burg Zug Museum. It is a profoundly moving record of the experiences of young survivors from Nazi concentration camps who were brought to Switzerland to recover after the Second World War.

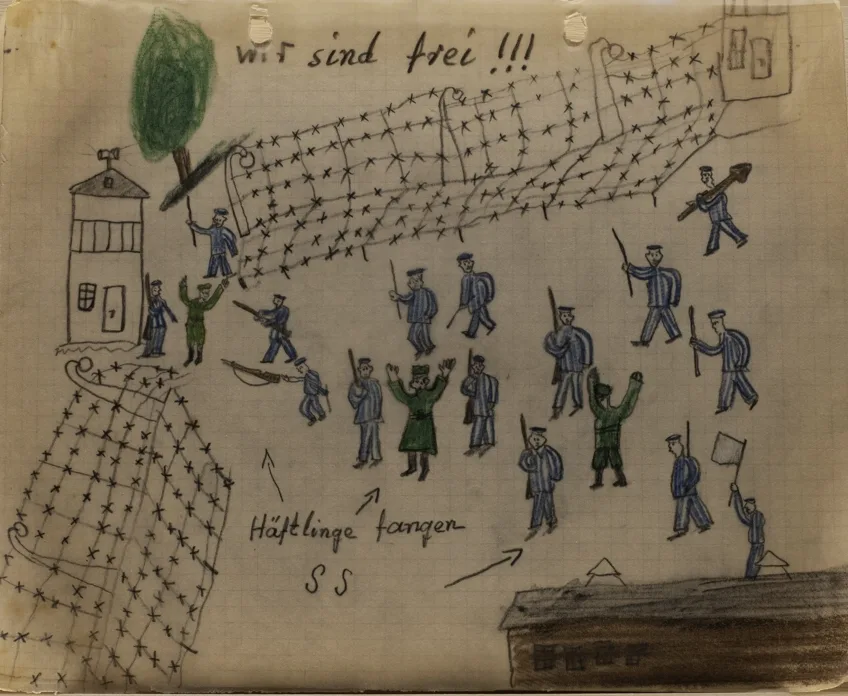

They have stretched miles of barbed wire, horizontally and vertically, very densely and evenly. It forms towering, insurmountable enclosures, drawing the brutal line between life and death. The barbed wire dominates the drawings. Sometimes the barbs appear huge, as if under a magnifying glass. You see what they're getting at right away. There is no escape from the murderer's system.

In one, a man in the blue and white striped uniform worn by prisoners, portrayed small like a sacrificial offering, stands in front of the barbed wire wall, arms outstretched. “Tot durch Elektrische Dratt” (Death by electric wire) is written over him in an unpractised hand. The misspellings are also revealing. The young authors were sentenced to do forced labour instead of going to school.

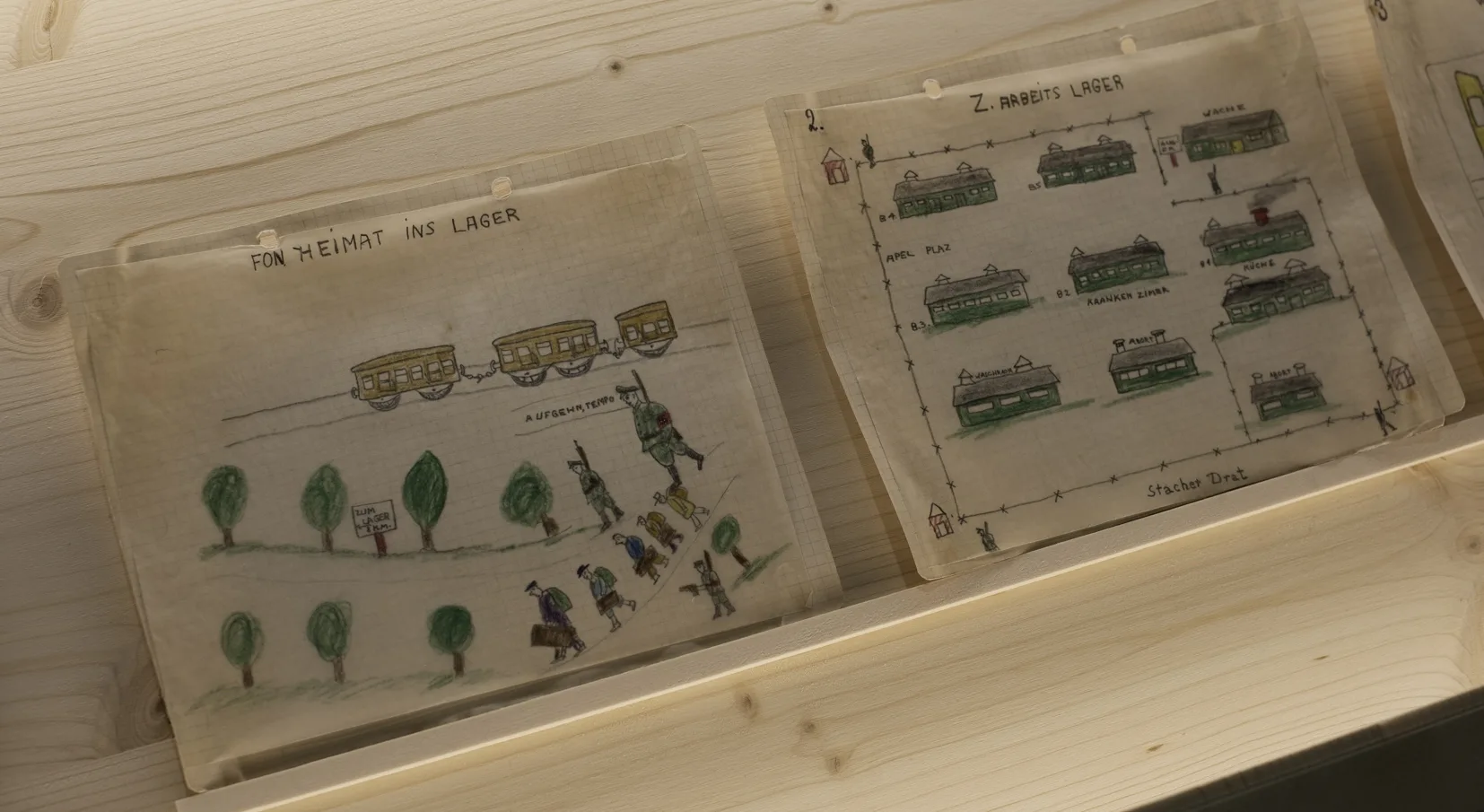

“Gezeichnet” is the deliberately ambiguous title of the exhibition at Burg Zug Museum that gets right under your skin. The drawings were done by those known as the “Buchenwald children”; children and teenagers from the Nazi concentration camp at Buchenwald near Weimar. The dominant theme is the everyday life of the camp, strictly regulated and brutally supervised by the Nazi gangs, with its beatings, roll-call and gallows. The admission routine frequently appears: “Showering,” “Disinfecting,” “Looking for gold,” illustrated by a doctor reaching into a new arrival's open mouth. They had all obviously learned the “concentration camp ABC” (appeal, block, capo, ..., fence, ... Muslim, ... roll call, ..., tattooing, vaccination, weed soup, ...).

“From Home to the Camp” and “To the Labour Camp”, Kalman Landau, 1945.

Archives of Contemporary History ETH Zurich

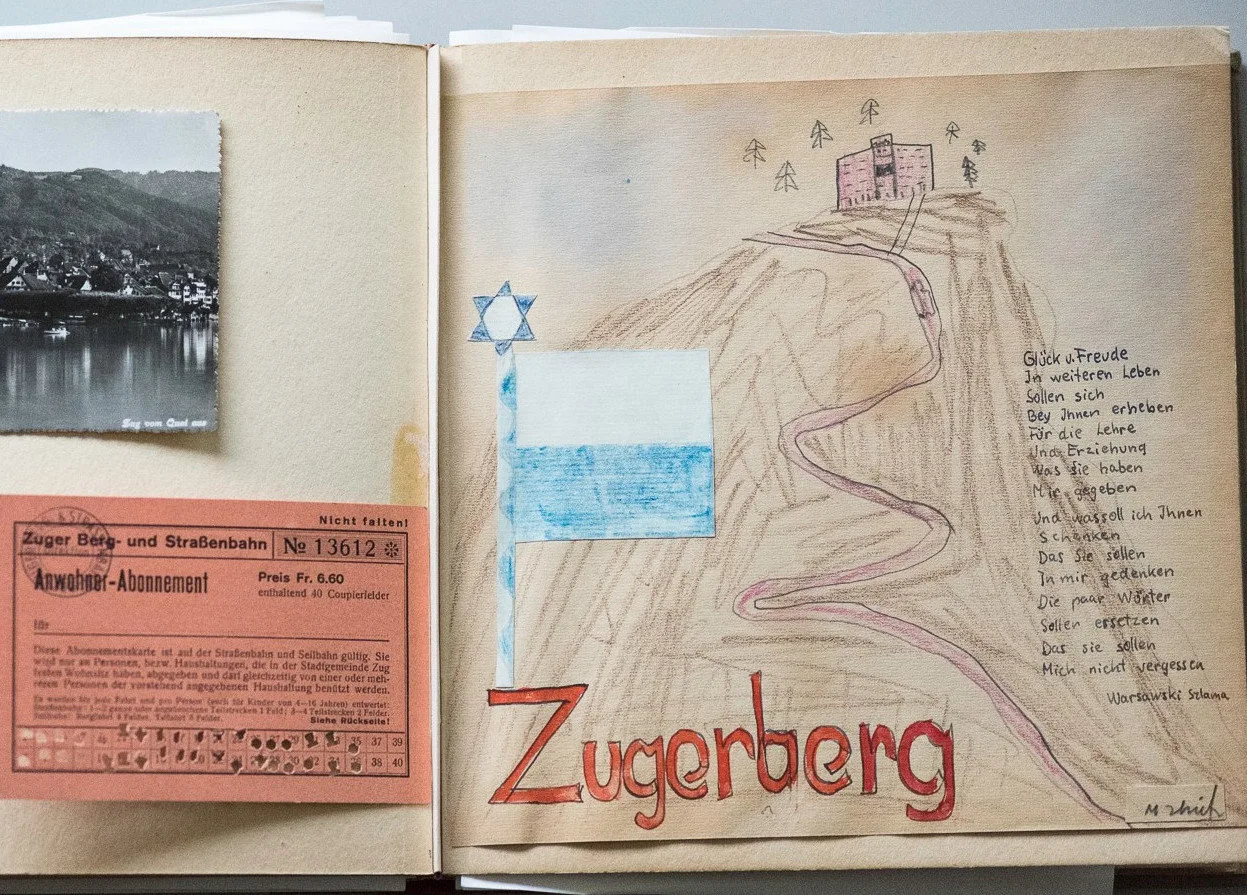

So how has the Zug Museum managed to exhibit these testimonies to the Holocaust in public for the first time? The short answer is that children and young people were brought to the “Felsenegg” children's home on the Zugerberg, which today is part of the Institute Montana boarding school, to recover in the summer of 1945. They came from the Buchenwald concentration camp which had been liberated by the Allies shortly before. The people who looked after them kept the drawings, even taking care to copy them, because they recognised straight away that they were valuable contemporary documents. Some were published as early as 1946 by the then editor-in-chief Arnold Kübler and Charlotte Weber in the magazine “du”.

But there's more to the exhibition than just the drawings, as powerful and shocking as they may be. Above all, the context of their creation is presented with exemplary care. The exhibition organisers refer, among other things, to contemporary accounts that have already been published, as well as to current studies that can be viewed in situ.

A view of the exhibition in the Burg Zug Museum.

Photo: Regula Bearth, © ZHdK

How did these “Buchenwald children” end up in Switzerland and on the Zugerberg, of all places – and what prompted them to start drawing? Unlike the children's drawings from the Theresienstadt concentration camp that are well-known about today, for example, the Buchenwald children's pictures were created afterwards. They are the first recorded memories of the few concentration camp survivors. Every single page offers a glimpse into an abyss.

The context was “Schweizer Spende”, the Swiss relief effort at the end of the war. The large-scale fundraising campaign, which the Federal Council ran from 1944 to 1947, was intended to be a humanitarian gesture by Switzerland to Europe, which had been devastated by war. The Swiss people whose lives had been spared this horror were shocked and shamed into opening their wallets. Advertising brochures juxtaposed images of hungry children, some of them even murdered, with photographs of affluent, treasured Swiss children. Including federal funds, around 200 million Swiss francs were raised (around a billion in today's money).

As we learn, the campaign was not entirely selfless: It had become clear in 1944 that the Allies would win the war. With this gesture, officials in Switzerland wanted to overcome their own foreign policy isolation during the war. The Red Cross, for example, carried out the relief campaigns in around 18 European countries, including Germany, bringing children such as those from Buchenwald to Switzerland to recover.

And so, the 107 young people were welcomed on the “Felsenegg” in 1945. Don't picture the place as being some sort of oasis of well-being. Far from it. Those very same children who had narrowly escaped death had to do military drills once again. The Red Cross, which was in charge of the situation, was under military supervision. This was compounded by practical problems. The carers who had been hastily recruited, idealistic women and men, mostly young and relatively inexperienced, had expected to be assigned children aged between six and twelve. But they had been murdered first in the Nazi camps as they were barely capable of work. Instead, they tended to encounter young men, some getting on for twenty, who had somehow made it onto the transport.

“Zugerberg” Drawing by Michael Urich, 1945.

Archives of Contemporary History ETH Zurich

“We are free!!!”, Kalman Landau, 1945.

Archives of Contemporary History ETH Zurich

The diaries and letters of the carers and the children in their charge illustrate very vividly how it was possible to bring the severely traumatised survivors back to some sort of normality. The exhibition not only speaks through documents, it is also reflected in the words written and crafts made by pupils on poor quality paper. In addition to film extracts, large portions of these texts are also played realistically at various audio stations. However, you can also listen to some of the last surviving “Buchenwald children” and Holocaust witnesses, most of whom live in Israel, recounting their experiences. Both Switzerland and the Jewish organisations were keen to move the “Buchenwald children” on there quickly. It's a whole chapter in itself that is only briefly touched upon.

However, the drawings remain at the heart of the exhibition created with the collaboration of the Institute for the Performing Arts and Film at Zurich ZHdK (University of the Arts). The series by Kalman Landau, which is almost like a comic strip, is particularly striking. The 17-year-old systematically records all aspects of camp life in vignettes, together with their most disturbing images, corpses heaped in piles in the gas chambers. The matter-of-fact way in which he captures mass murder demonstrates a distanced coldness that sends shivers down your spine. You get the feeling that this distance is the protective shield you needed to acquire in the concentration camp so as not to break down from the unimaginable horror of it all.

It is to the exhibition's great credit that its understated staging allows the rather quiet nuances and undertones, such as the emotional relationships between the carers and the children, deeply traumatised yet grateful as they were, to come through in the drawings and texts. The material on display at Burg Zug is more than “just” another chapter in the historical analysis of the Holocaust. There are still people alive today who bore witness to things that are barely imaginable to most of us. The question of how we approach them, whether we can help them put their horrors behind them, and how we go about this, is not historical, but highly topical.

drawn. The “Buchenwald children” on Zugerberg

21.11.2018 – 31.03.2019

Recommended from 12 years. Including guided tours for school classes.

www.burgzug.ch