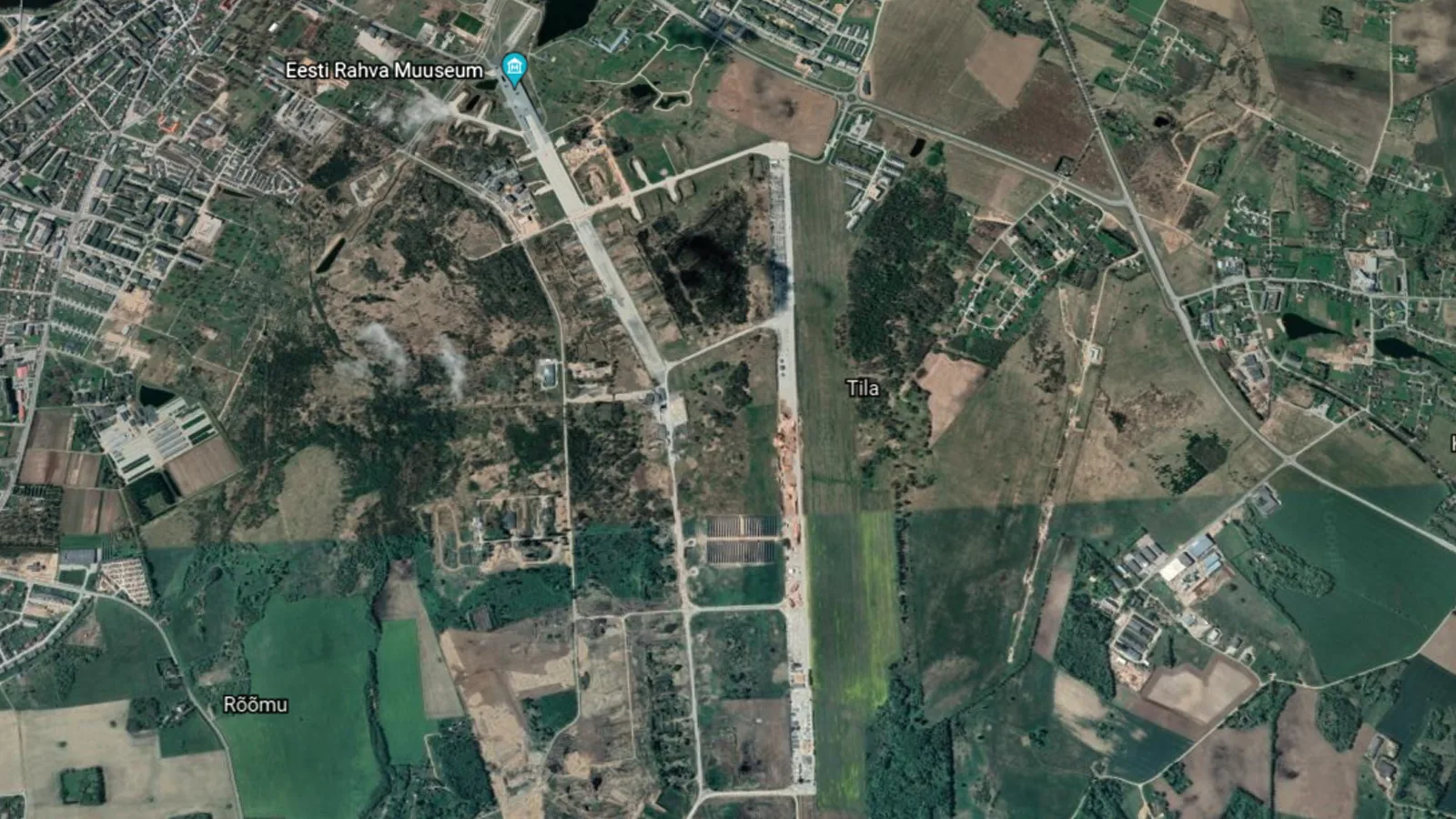

A runway into the future

The new building of the Estonian National Museum, opened in 2016, is spectacular in every way. The building reveals a lot about the eventful history and the present day self-image of the smallest of the Baltic countries.

Estonian National Museum Tartu

The museum offers permanent and temporary exhibitions (also in English). Tartu can be reached comfortably by train from Tallin in just under two hours.

Those who shy away from traveling to Estonia can also visit some virtual exhibitions.