Women on strike!

One hundred years ago, a quarter of a million people downed tools in the general strike. What role did women play in the three-day strike of November 1918?

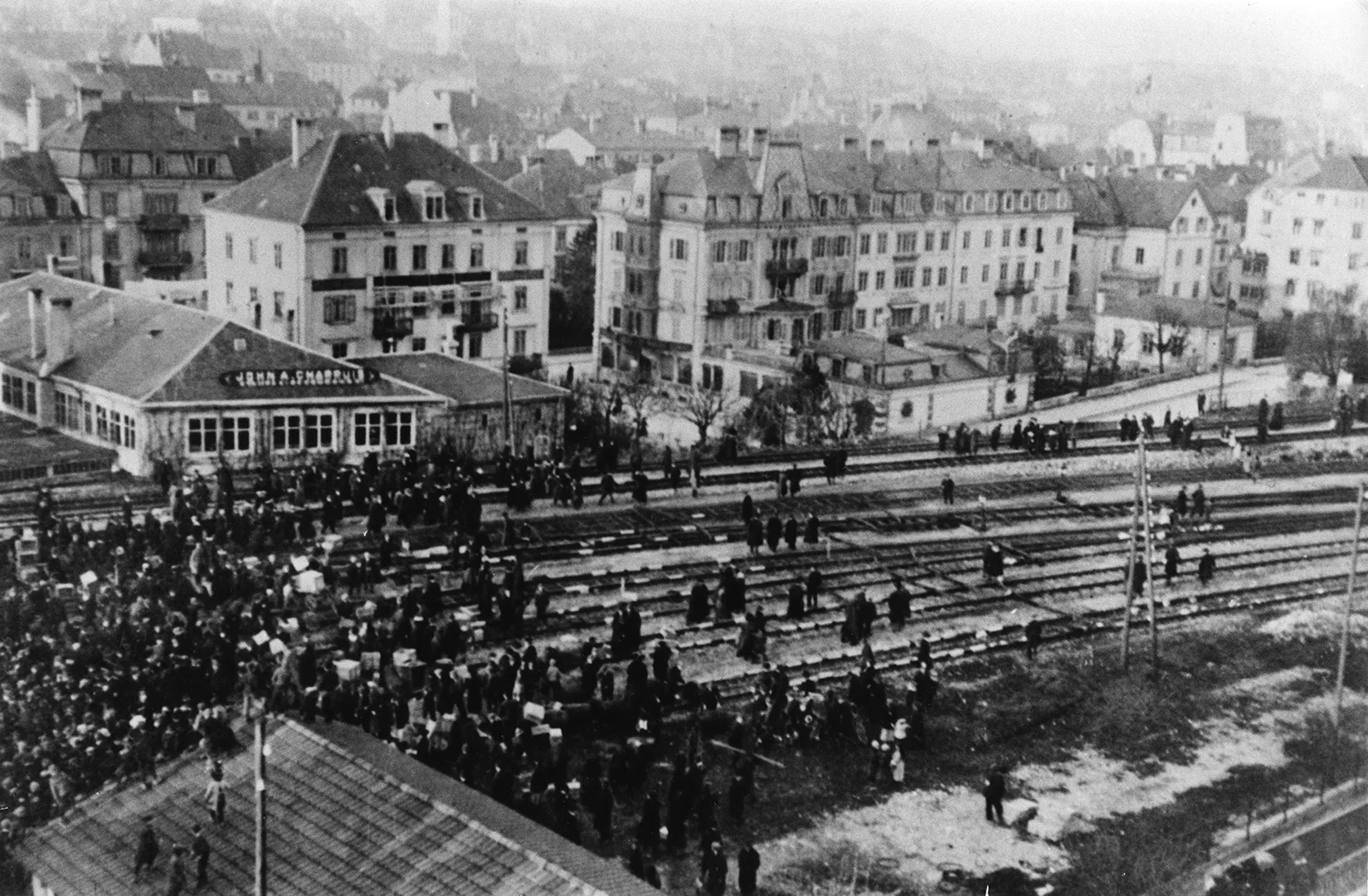

Posted at the Nordbahnhof in Grenchen on the last day of the general strike, Captain Theodor Schnider faced a tough decision: should he give the order to shoot, or not? Demonstrators had set up a track blockade, and Schnider and his company had the task of protecting the station. A lieutenant requested the order to shoot, but Schnider decided against it. He justified his decision with the fact that, among the strikers on the rails, there were many women and children positioned right at the front. This episode shows not only that women were involved in militant strike action, but also that their participation had an impact on the course of events during those intense few days of November 1918.

It wasn’t only at this track blockade in Grenchen that women were present. If we look at the activities of women during the general strike, it becomes clear that they played a major role both on the side of the strikers and on the opposing side of the non-striking middle-classes.

The striking women

Following the proclamation of the general strike, the social democratic women’s agitation committee called on female workers and working-class women to take an active part in the strike. And these women answered the call. They were involved in supplying food, both organisationally – in Zurich, they set up a special strike emergency support committee at the Volkshaus – and in practical terms, cooking food on their own stoves. They organised childcare: as schools were closed because of the Spanish flu, the provision of childcare during the days of the strike was particularly important. To make sure the children would not become involved in conflict with the military on the streets, the social democratic women’s associations in Zurich, together with the social democratic school association and the Zurich social democratic teachers’ union, arranged excursions, taking the children of working-class families off to the outskirts of the city in the afternoons. Women also took part in strike assemblies and in addition organised their own women’s assemblies, for the purpose of attracting people who had not yet fallen in with one side or the other to the trade unions and SP women’s groups. Shoulder to shoulder with the men, they marched on the streets in demonstrations, and they took part in track blockades. They also picketed inns and taverns to enforce the alcohol ban imposed by the strike leaders, and tried to persuade the soldiers not to take action against the strikers and to refrain from shooting, or fire into the air, if given any order to open fire.

The dilemma of the middle-class women

On the opposing side, too, women got involved during the days of the strike. They supported the army and were involved in caring for the soldiers who were sick with flu. In Zurich, the Frauenzentrale, an alliance of middle-class women’s organisations, together with the soldiers’ welfare association (Verband Soldatenwohl), organised the infrastructure and care for around 2,000 flu-affected soldiers within a very short space of time. These middle-class women vehemently opposed the strike. However, a demand from the OAK put certain members of the middle classes in a quandary: active and passive women’s suffrage was ranked a prominent second in the list of demands. Many people had fought for years for the implementation of this demand. Emilie Gourd, chairwoman of the Swiss Association of Women’s Suffrage, publicly expressed her support for the demand and on the very first day of the general strike, 12 November 1918, sent a telegram to the Federal Council (Bundesrat) calling for women to be given the right to vote. This act elicited divided reactions among the middle-class suffragettes: while some criticised Gourd for her alleged solidarity with the strike, others praised her, saying she had recognised which way the wind was blowing and had acted correctly. After all, on 12 November 1918 women’s suffrage was enshrined in law in both Germany and Austria.

In the aftermath to the general strike, two motions for women’s voting rights were tabled, by SP National Council member Herman Greulich and liberal National Council member Emil Göttisheim. For the first time in Switzerland’s history, women’s suffrage was on the agenda of the federal legislature. However, both motions vanished on to the dusty shelves of the Federal Council without being discussed.

Even though women’s suffrage was not introduced, the strike was by no means felt by women to have been merely a defeat. The socialist doctor Minna Tobler-Christinger described the feelings of fellowship and solidarity women experienced during the strike as follows: “All those who took part had become friends. People patted each other’s hands, smiled at one another. You had profound philosophical discussions with strangers. You rejoiced together over a strike successfully seen through.”