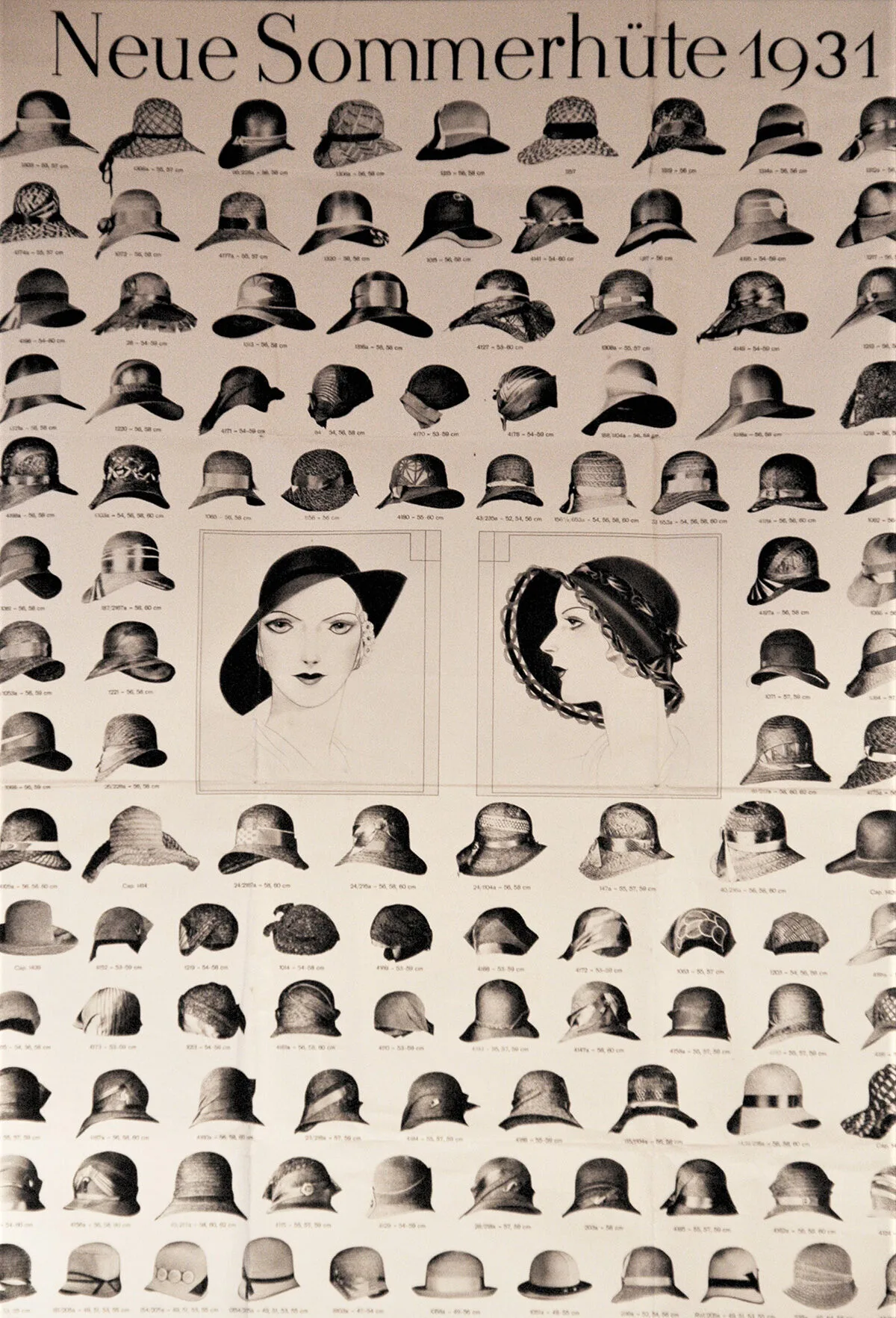

The hat was good for the economy

In the 18th century, straw-weavers and hatmakers had a bad reputation in Switzerland. They were condemned as lazy. A century later, hat-making became a flourishing business.

Import from the south

Innovative son of the Ritz family

Wigs and hairstyles sound the death knell