Feeling the heartbeat of the museum

His idiosyncratic aesthetic has made film director Wes Anderson famous. Now, working with Juma Malouf, he has set up an exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The result: a contemporary cabinet of curiosities.

A container for one hundred ostrich feathers, part of the regalia of the Austrian Order of the Iron Crown. Two cherry stones carved with miniature scenes. A bizarre vessel made from the world’s biggest emerald. Plans for sleigh rides inside Vienna Castle. And the shrew mummy in a coffin which gives the exhibition its name: ‘Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures’. These are just five examples from the more than 400 exhibits which film producer and director Wes Anderson (most recently known for ‘Isle of Dogs’) and his partner, author and illustrator Juma Malouf, have selected – or more precisely, unearthed – from the extensive inventory of the Kunsthistorisches Museum and related collections, numbering an incredible four million or so objects.

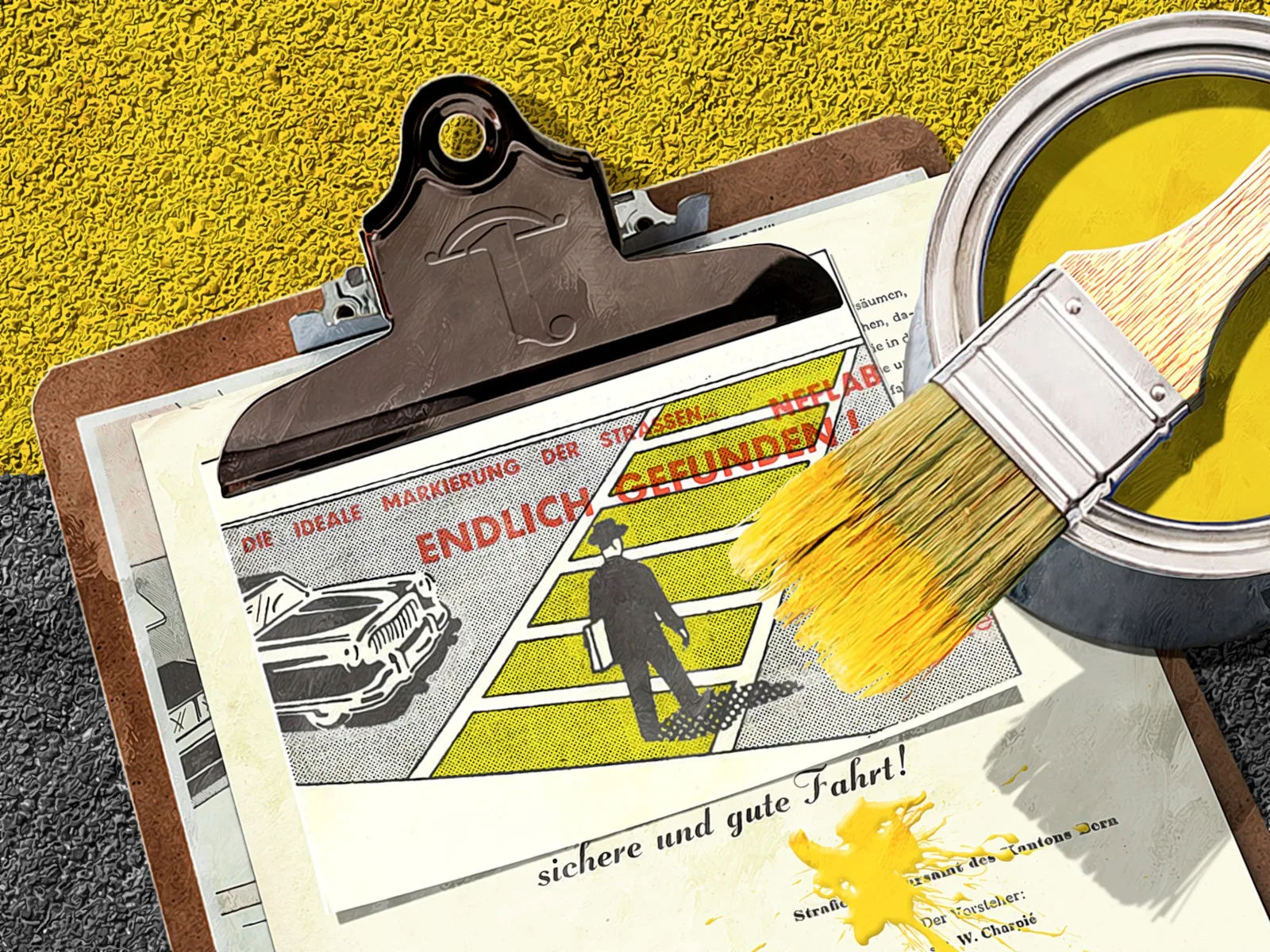

But the charming mix is less bewildering than it may at first sound. Eight cabinets are included in the exhibition, with themes that quickly become clear to the visitor. One cabinet, for instance, groups together miniatures, among which, in addition to the above-mentioned cherry stones, are models of Japanese musical instruments and Javanese baskets. The fascination with miniature objects is typical of cabinets of curiosities from days gone by. One room displays paintings of children represented as little adults, in accordance with the ideal of previous centuries. The genre of the quaint is there in an assortment of cases and containers, among them the one for ostrich feathers and some for crowns and monstrances. As a mischievous punchline, this room also features an empty museum display case. Other organising principles are the colour green, wood as material, and themes such as animals and portraits.

Wes Anderson & Juman Malouf in the exhibition.

© KHM-Museumsverband. Photo: Rafaela Proell

The clever mise en scène makes each individual display case, each wall, a full-fledged tableau, in which each object or image seems to be in conversation with others. With these meaningful contiguities, Anderson and Malouf are giving voice to another guiding principle of the cabinet of curiosities: the fascination with and inspiration provided by the specific object, whether it is produced by nature or created by an artist. Anderson and Malouf are aware that you cannot write the history of the modern museum without entering the studios of the Renaissance scholars, without delving into the cabinets of curiosities and treasure chambers of absolutist rulers. In these places, in both a material and a spiritual sense, were laid the crucial foundations for museums, which have become increasingly public, and increasingly scientific, since the Enlightenment.

Nowhere else in the world is this history, at the same time part of the cultural history of Europe since the Renaissance, as vivid as in the treasure chamber of the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna. Today, the Museum is a fusion of a host of legendary collections that were owned by the Habsburg dynasty. By today’s standards, the collections are perfectly presented.

Paintings of children who are portrayed as adults according to the ideal of past centuries. In the front: Pieces of a boy's armour, around 1568/70.

© KHM-Museumsverband.

Perhaps too perfectly. Because, in their elegant presentation in the imposing galleries of the treasure chambers, one now feels little of the passion that bound the erstwhile collector to each individual one of his or her objects – the heartbeat of the museum, so to speak.

In order to reawaken this perception, for a number of years now the KHM has been inviting guest curators with a particular vision; before Anderson and Malouf, previous curators were artist Ed Ruscha and writer Edmund de Waal.

This idea, of which Andy Warhol’s 1969 piece ‘Raid the Icebox’ is a famous example, always works best if the guests are original enough, and bold enough, to break through the museum routines of both the custodians and the public. Anderson and Malouf have succeeded brilliantly; they have clearly pushed to their limits quite a few of the Museum’s curators, those who act as guardians of the treasures entrusted to them. Indirectly, in fact, they raise the question of the reasons for the collections, and the standards of today’s museums: Why, in our culture, is a thing considered so precious and worthy of preservation that we spare no effort in safeguarding it? And what makes some nondescript object so valuable?

Coffin of a shrew's mummy. Egypt, around 4th century BC.

© KHM-Museumsverband

But the public is challenged as well. Because once you’ve grasped the rough structure of the selection, it becomes a game of detectives. The explanatory pieces for the exhibits are neatly set out in an accompanying booklet. Only the audio guide offers a bit more guidance.

The lack of information has a purpose. The museum as enlightener, with its scientific and educational standards and devices, with the familiar guardrails and supports of chronology, provenance, authorship and historical context, is replaced by a more fluid universe of surface attraction, eye candy, allusions and associations, with the risk of trailing off into the realms of the completely random – ultimately, very similar to the unending image machine that is the Internet. Every visitor is, effectively, put to the test: What elicits a response in me, and why? Am I ready to engage with such a radically intimate presentation? What correlations do I see? Where do I want to find out more?

This provocation also works if one knows nothing about Anderson and Malouf and their work. But the exhibition unfurls its true charm if one is familiar with Anderson’s aesthetic. Children as actual adults, as heroes of history? One of the director’s obsessions. The attention to detail, whether in the accoutrements or in the mannered design of a typeface? Anderson’s trademark. The craze for a particular colour? Just as obvious – even if in the films it’s usually yellow. Fans will effortlessly discern other common threads, such as a predilection for books, music, animals, peep shows, symmetries and patterns.

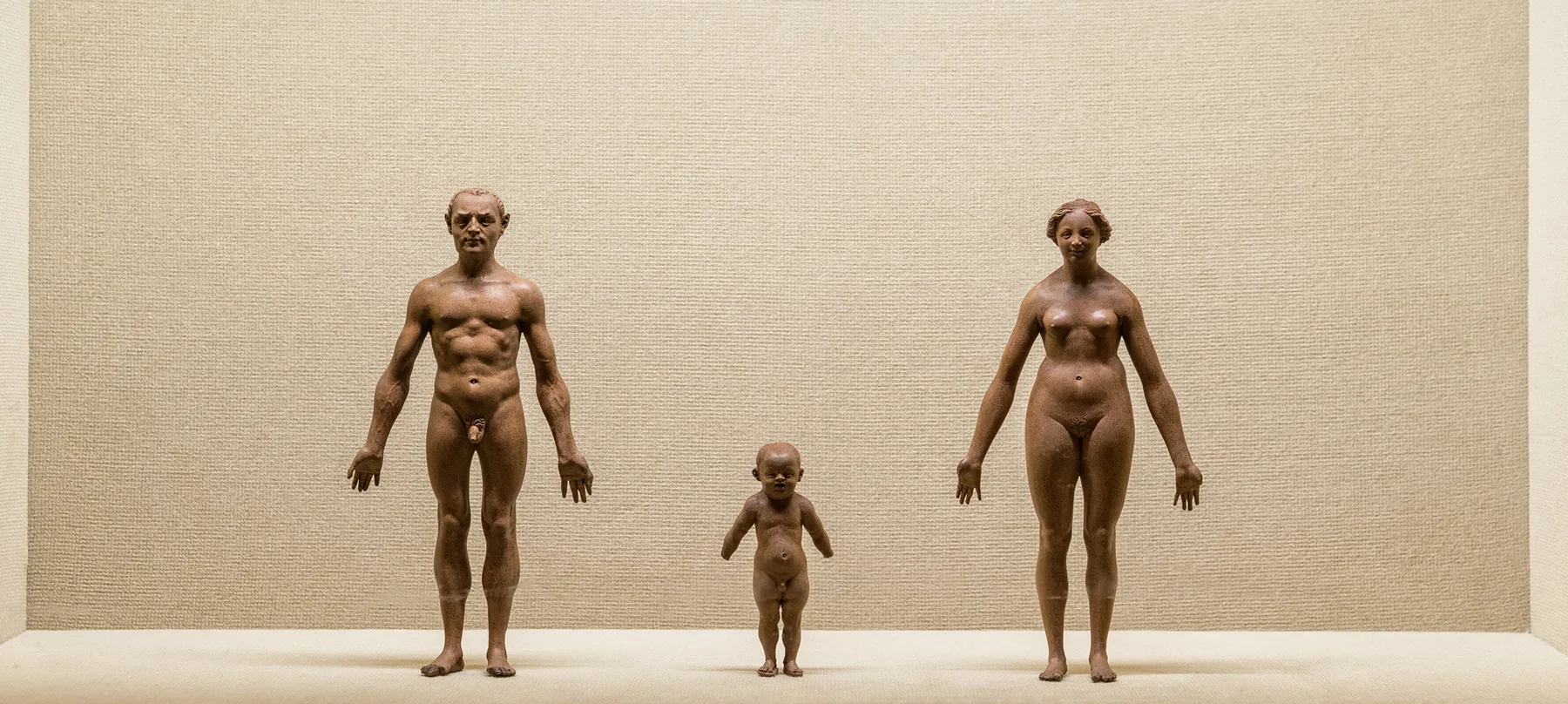

Proportional figures of a nude man, boy and woman. Germany, around 1550.

© KHM-Museumsverband

And thus, in this contemporary revival, the original gesture of the cabinet of curiosities is repeated, as depicted at the start of the exhibition in a tableau by Frans Francken the Younger from around 1620: The prince is enchanted by curiosities, the prince makes a selection, the prince presents his selection, and thereby presents himself. Except the prince is now a particular creative celebrity with all the glamour that goes with that.

You may, as when you watch a movie, immerse yourself for a short time in a universe created by others. You could wallow in this new universe, and leave it at that. But you could also resurface and reflect on the crucial step that once, at a certain stage, took the development of the museum from subjective, arbitrarily chosen ‘sampler’ to informative educational institution. In any case, in this day and age the generalisation of the cabinet of curiosities principle would be more of a step backwards for the museum, as it would for society as a whole. This too Anderson and Malouf seem to suggest with a subtle gesture: towards the end of the exhibition they show a likeness from 1564 of the dead Emperor Ferdinand I – the man who, in the 16th century, established the first cabinet of curiosities in Vienna’s Hofburg Palace.

Curator Jasper Sharp on the exhibition.

Video: KHM Wien/YouTube

Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and other Treasures

Wes Anderson and Juman Malouf

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna until 28. April 2019, after that at the Fondazione Prada in Milano