Photo: NASA

Swiss technology on the moon

On 21 July 1969, humans walked on the moon. Around the globe, the earthlings left behind followed live on their TV sets as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin embarked on the greatest adventure of the 20th century. In the USA the ‘space race’, driven by the Cold War, saw vast amounts of state funding poured into the project. Scores of NASA suppliers from Switzerland also benefited from this. Swiss cutting-edge technology contributed to the success of the Apollo XI mission in a number of areas.

Neil Armstrong’s words were certainly apt when he said, upon setting foot on the moon, ‘That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind’. In a moment full of pathos, the success of the moon landing was touted as a feat achieved by all of humankind. But the media response in Western Europe quickly took on national perspectives. Germany was proud of aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun, who had played a key role in the Apollo programme, and did its best to suppress his Nazi past. Even the Austrians claimed von Braun as one of their own, as his parents had lived near Salzburg after the war. The Italians highlighted the achievements of Rocco Petrone. An engineer of Italian descent, Petrone was responsible for the launch of the Saturn rockets at Cape Canaveral. The numerous women, many of them African-Americans, who as mathematicians and programmers made a crucial contribution to the success of the lunar mission remained largely unmentioned in the press at the time. As for Switzerland – did we have any ‘big men’ whose involvement we could crow about? In this country, the press celebrated university research and Swiss industry. On 24 July 1969, the Schweizerische Handelszeitung newspaper summed up in a patriotic subheading: ‘Even the crossbow symbol went to the moon’.

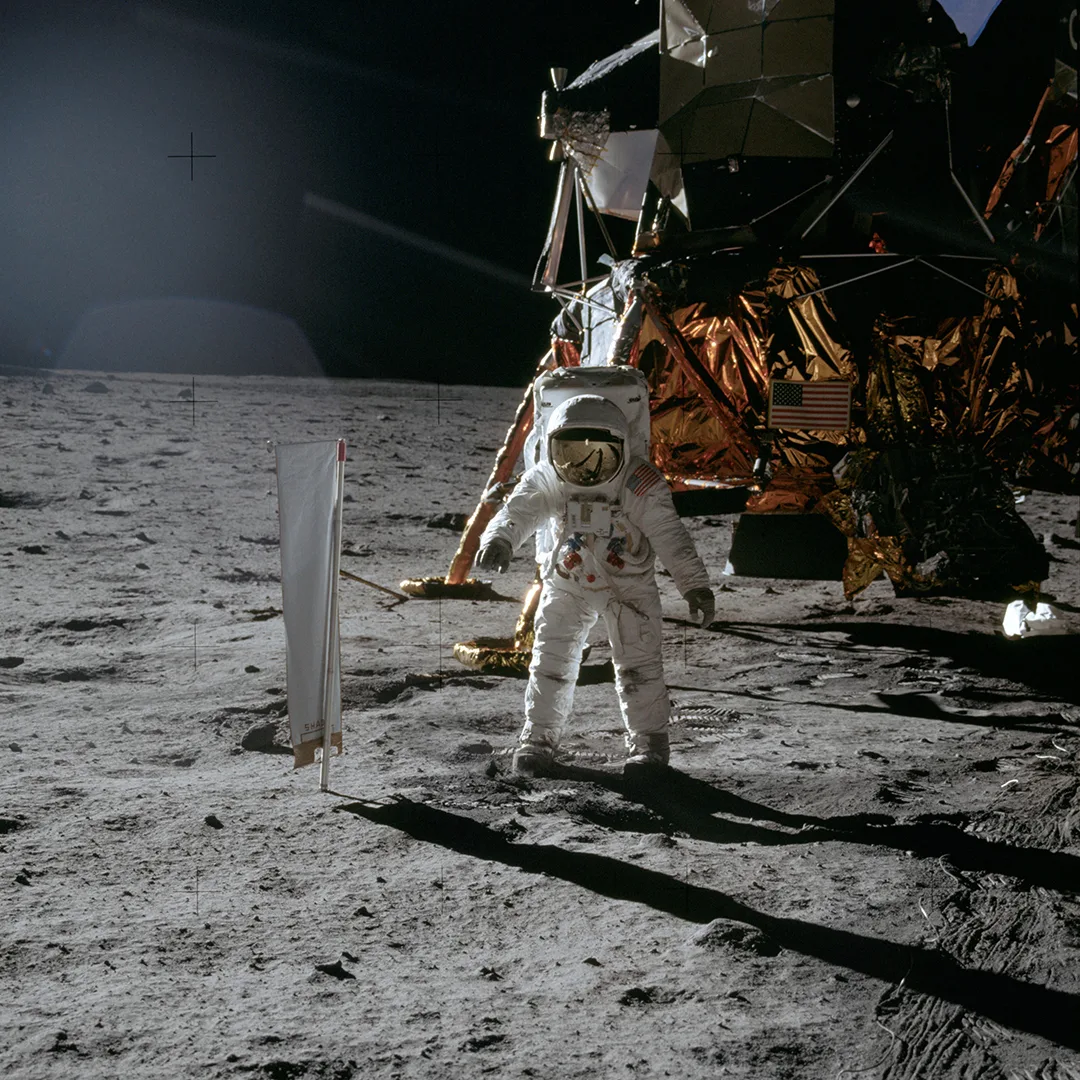

In the following, we’d like to remind people once again of all the individual ‘Swiss Made’ contributions to the success of Apollo XI. Let’s start with the science. Before the two astronauts even hoisted the American flag on the moon, Buzz Aldrin set up a solar sail from the University of Bern, as part of the Solar Wind Collector experiment (SWC). The piece of aluminium foil approximately one metre high measured the solar wind, and was brought back to Earth. Professor of Experimental Physics Johannes Geiss and his entourage analysed the well-travelled piece of metal mostly at the Physics Institute of the University of Bern. The data obtained from the mass spectrometer allowed new conclusions about the formation of our solar system and the big bang. The SWC experiment was the only non-American research project the Apollo XI crew had on its books.

Four ‘data acquisition’ film cameras were also used to collect data. Mounted both on the command module and on the lunar module, the 16 mm cameras recorded the events for later evaluation. The cameras’ high-performance lenses were manufactured by Kern in Aarau. The firm, which was closed down in 1991, specialised in precision mechanics and optical equipment. Two of the lenses were custom designs and were developed specifically for the tough conditions of space travel. As the firm boasted, the computation of the optical characteristics required over 100 million arithmetical operations on a mainframe computer. The Aargau firm also supplied NASA with precise theodolites, which served as drilling angle instruments during construction of the Saturn V rocket.

Alongside astronaut Buzz Aldrin, the sun sail from Switzerland is clearly visible. In the background is the Apollo XI lunar module. Neil Armstrong pressed the shutter.

Photo: NASA

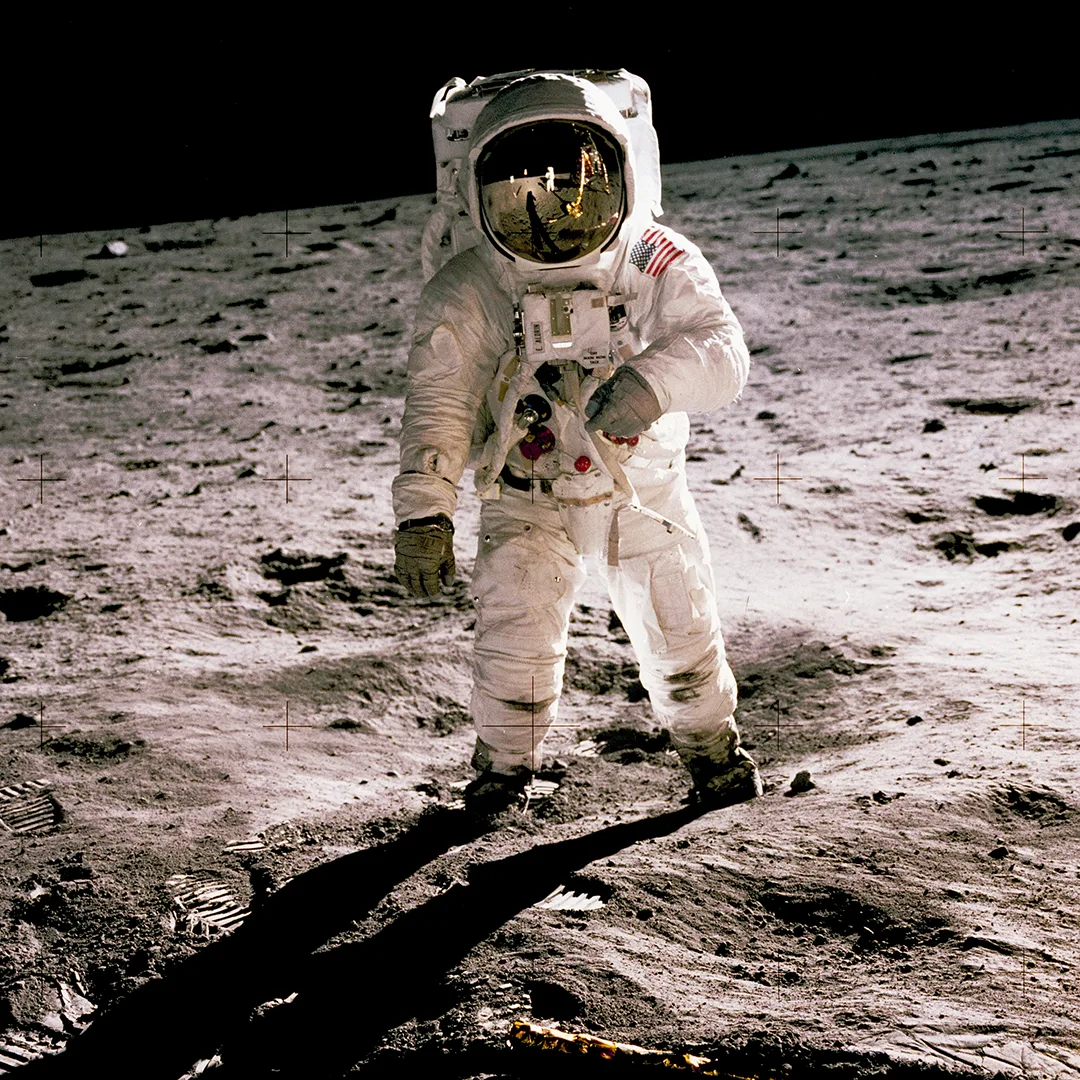

What is probably Switzerland’s most famous contribution to American space travel also came from the southern foothills of the Jura. Since 1965, US astronauts have been equipped with Omega Speedmaster chronographs from Biel on their space missions. In NASA testing the mechanical Omega creation, with its manual winding, had outperformed the competition and withstood pressure fluctuations, extreme temperatures, magnetic fields, high speeds and intense vibrations. Because the electric on-board chronograph failed, Neil Armstrong left his Speedmaster on board the landing module as a back-up. On Buzz Aldrin’s wrist, the Omega watch was then used on the surface of the moon – and gave the Biel watchmaking firm a marketing angle few could hope to rival. To this day, the ‘Moonwatch’ continues to be produced in virtually the same model as in 1969.

Buzz Aldrin standing on the moon on 21 July 1969. The Omega Speedmaster, held in place by a Velcro strap, is clearly visible on his right arm.

Photo: NASA

Buzz Aldrin also carried the mechanical watch from Biel on board the lunar module.

Photo: NASA

Aldrin wore his Speedmaster over his spacesuit, using a Velcro wristband. Hook-and-loop fasteners were also used in the spacesuits and in the Apollo capsule. Fastened down with Velcro, items of equipment defied the state of weightlessness and did not float around freely. Even the soles of the astronauts’ shoes were fitted with Velcro trim. The men could get the necessary purchase on the matching elements in the capsule. The fastening material so liberally used by NASA was invented in western Switzerland by electrical engineer Georges de Mestral and patented in 1955. The brand name Velcro is a neologism created from the French words velours (velvet) and crochet (hook), and refers to the mechanical basis of the hook-and-loop fastener. Today the firm still has a branch in Assens, Vaud, but operates world-wide.

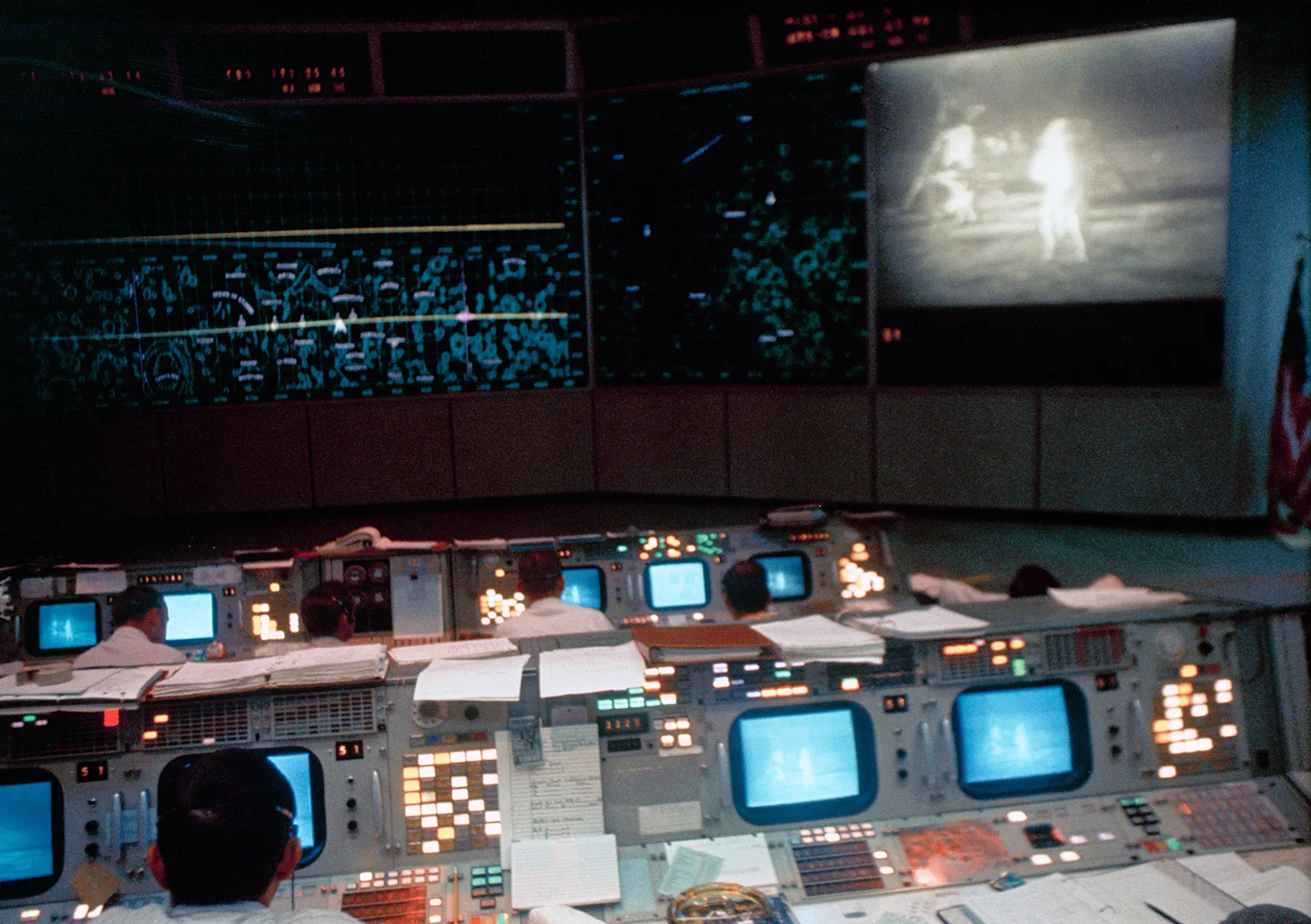

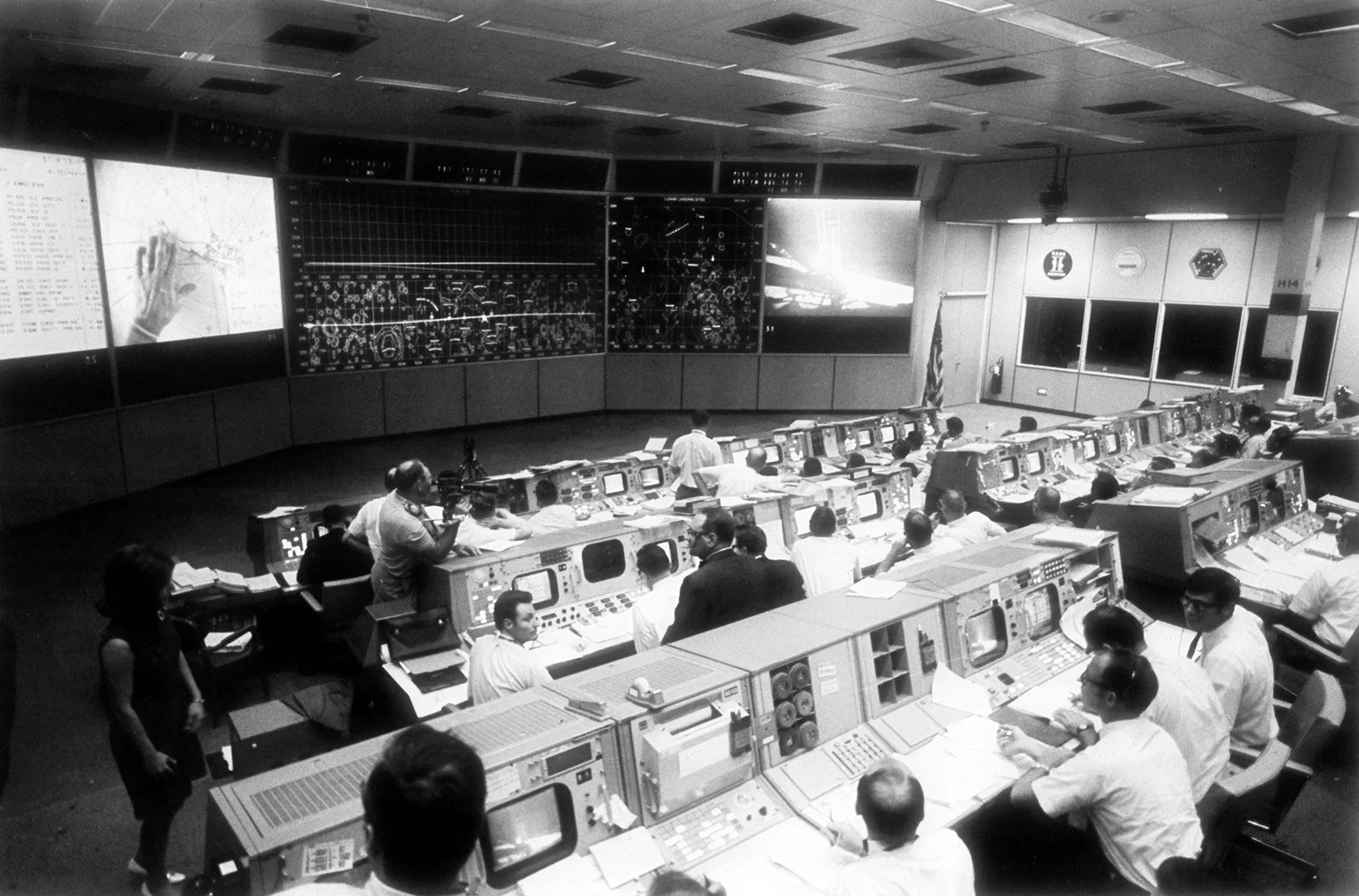

While the three astronauts of the Apollo XI mission were conquering the hostile environment of outer space, scientists and engineers at NASA’s Mission Control Center (MCC) in Houston were staring intently at scores of screens and projections. The condition of men, materials and technology had to be monitored in real time. The images projected onto the walls in the MCC came from Eidophor EP 6 projectors – another Swiss-made product. Projector technology was developed in the 1940s at ETH in Zurich and subsequently perfected in a kind of spin-off company before being commercially distributed. In 1969, Basel pharmaceutical company CIBA (now Novartis) and the firm Philips held the majority of shares in Gretag AG in Regensdorf, which manufactured the Eidophor devices. In a press release, the firm boasted: ‘We believe our contribution to the Apollo 11 project is one of the most significant from a Swiss perspective’, and noted that the 34 projectors at NASA were valued at approx. 20 million francs (about 60-70 million francs today). The marketing material also made reference to the projectors’ dependability. Between 1965 and 1969, the devices at NASA had a readiness rate of over 99.9%. Gretag AG was still involved in the projectors business into the 1990s. However, cheaper projector technology and management shortcomings led to the firm’s decline, and it ended in bankruptcy in 2002/2003. The archive of the Eidophor technology and a number of projectors – including an EP 6 model – are now in the Museum of Communication in Bern.

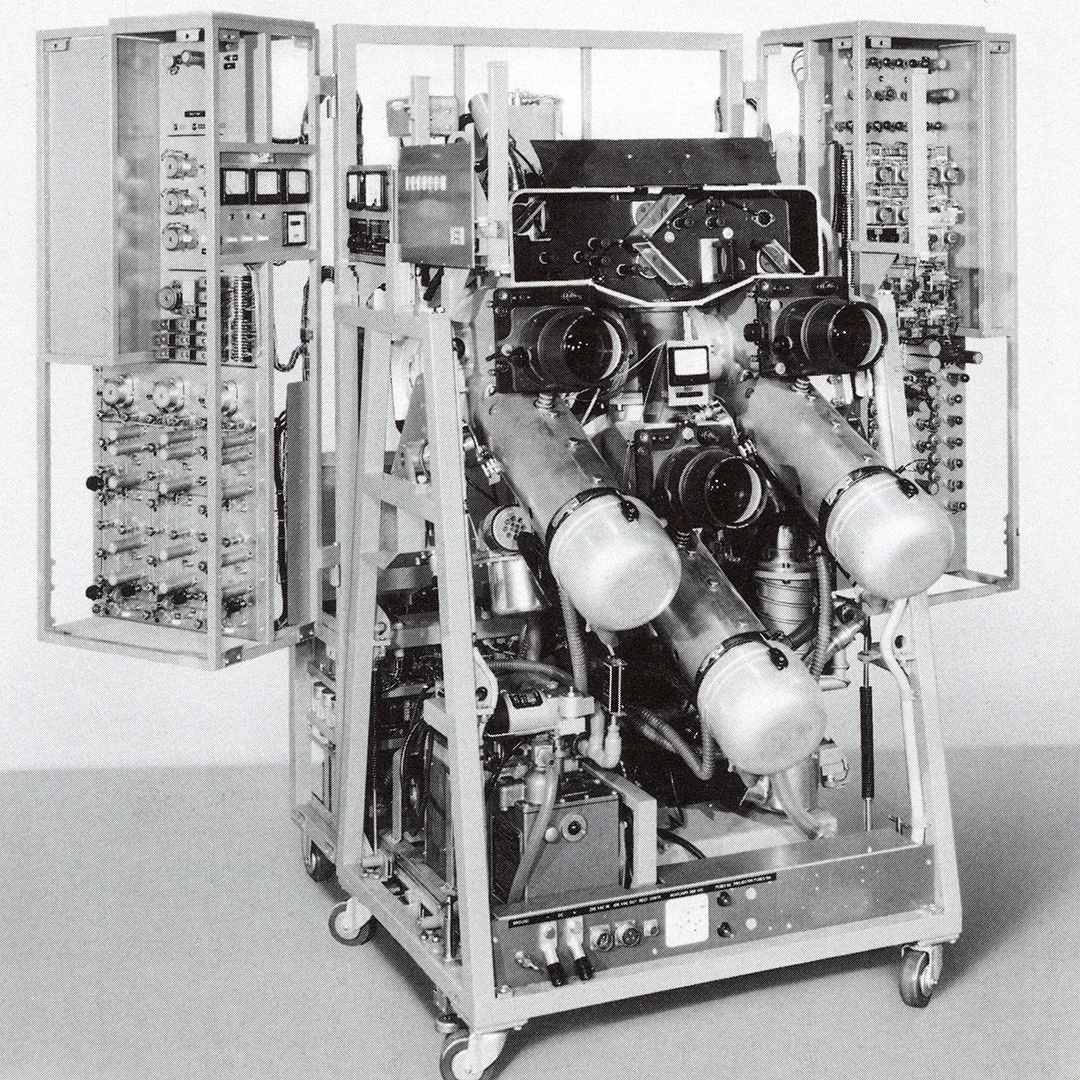

An American spy satellite from the Cold War? Of course not – this is what the Eidophor EP 6 looked like without its casing. Devices of this type were used in the NASA Mission Control Center in Houston. The Eidophor technology is based on a thin film of oil. Inside the device, this film is scanned by a cathode ray in high vacuum. The image ‘drawn’ in the oil is then illuminated and projected.

Museum of Communication, Bern

There is an Eidophor EP 6 projector in the collection of the Museum of Communication in Bern. Compared with a modern projector, the object dimensions are impressive: Height: 197 cm; width: 145 cm; depth: 105 cm.

Museum of Communication, Bern

Photo taken on 20 July 1969 from NASA’s Mission Control Center in Houston. Neil A. Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin can be seen on the Eidophor projection.

Photo: NASA

Promotional film for Eidophor projectors from the 1980s.

Museum of Communication, Bern

In the Mission Control Center, there was even more Swiss high-tech. The people in charge there were worried about the possibility of fires caused by overheating in computer systems and other electrical equipment. After the fire disaster in the Apollo I capsule in 1967, NASA was keenly aware of fire hazards. For that reason, in most NASA buildings Cerberus electronic fire alarms, known as ‘fire noses’, monitored the air in each room. Cerberus AG in Männedorf was integrated into the Siemens Group in 1998; the latter continues to produce fire alarm systems. But the technology used by Cerberus is no longer employed, as the ‘fire noses’ required a weak radioactive source.

The astronauts were also worried about heat and fire upon re-entering the earth’s atmosphere. However, a thermal protection shield on the Apollo capsule prevented the moon crew from ending up as a shooting star. The shield consisted of, among other things, Araldite epoxy resins specially developed by CIBA in Basel. These adhesives and fillers, in conjunction with straps and sandwich honeycomb composites, withstood temperatures of several thousand degrees Celsius and ensured a safe return to Earth.

While the Eidophor projectors throw moon landing images on the wall virtually in real time, ‘fire noses’ from the firm Cerberus AG in Männedorf monitor the Mission Control Center. One of these fire alarms is clearly visible on the ceiling in the top right-hand corner.

Photo: NASA

Some of the other Swiss contributions to the Apollo XI mission were given just a few lines in press reports. The following statements have not been subjected to any exhaustive source analysis – but they round out the overall picture of the subject: Aigle AG, an industrial electronics firm in Losone, supplied the Apollo programme with copper sieves, used in the construction of catalytic converters. The firm Industrie des pierres scientifiques H. Djévahirdjian S.A. (known today as DJEVA) in Monthey contributed synthetic rubies and sapphires. Synthetic sapphires from the Valais were used in the construction of the solar batteries, and in the windows of the Apollo capsule. This particularly hard material was supposed to protect sensitive parts of the capsule from meteorites. Mikron AG in Biel produced gearwheels for the capsule’s nautical system, and finally, Mettler Instrumente AG from Greifensee supplied NASA with precision instruments. The Americans carried out material inspections using a ‘thermo-analyser’ built in Switzerland. In addition, a Mettler precision scale ensured the astronauts’ freeze-dried food was accurately weighed. Indirectly, the Swiss armaments industry was also involved in the moon adventure. The Contraves Space Division supplied electronic components for various satellites (e.g. Intelsat 3), which played a role in the television broadcast of the moon landing. The firm Contraves was the armoury unit of the Oerlikon-Bührle Group.

Finally, it should be noted that it was not only the West for which Gretag AG, at least, supplied cutting-edge technology for space travel. As historian Caroline Meyer reveals in her dissertation ‘The Eidophor’, published in 2009, projectors from Regensdorf were also found in Soviet aerospace institutions.

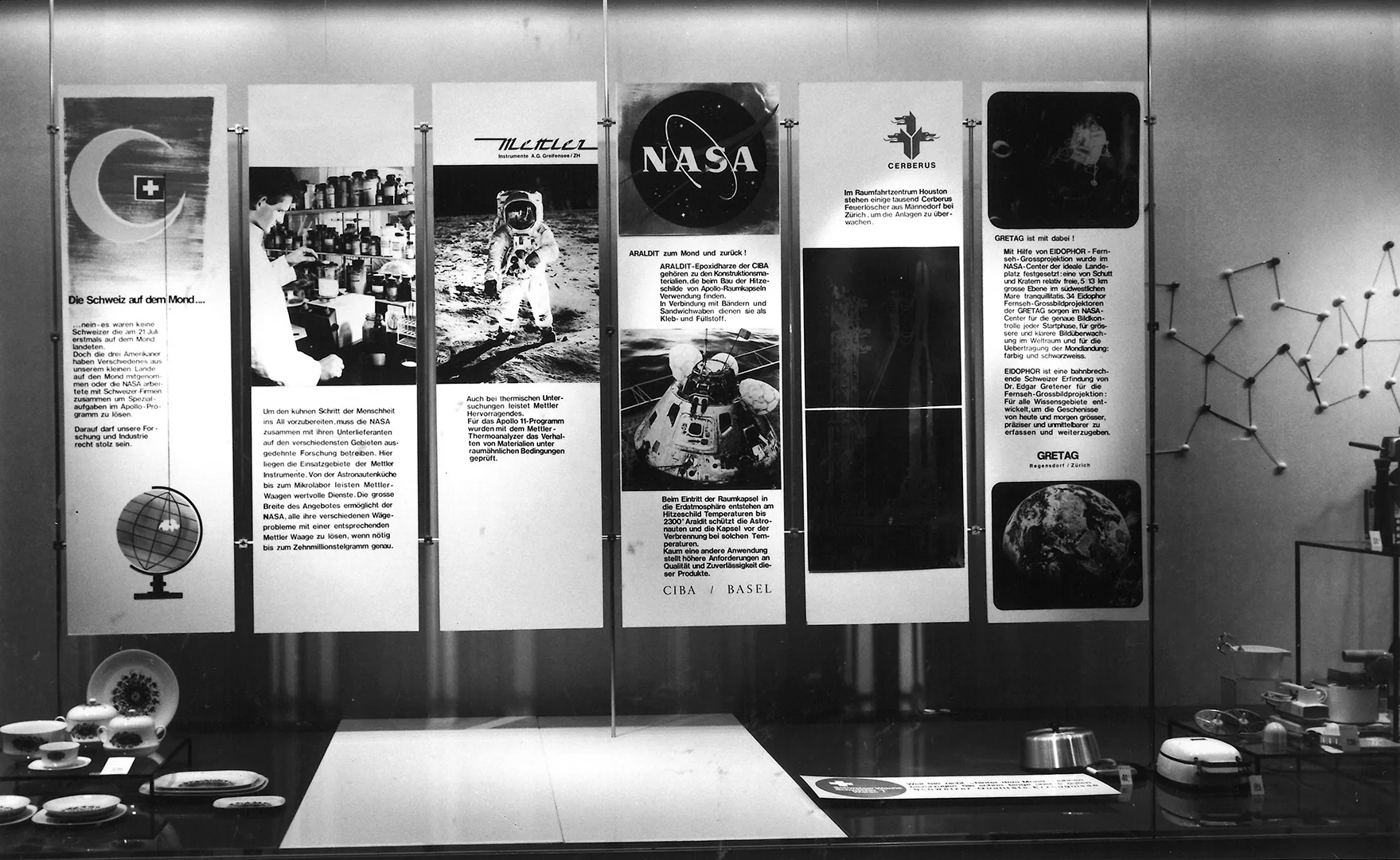

Mettler Instrumente AG from Greifensee was also part of the moon landing adventure, and used this fact in its advertising.

Museum of Communication, Bern

In autumn 1969, Bern department store Loeb also made use of Switzerland’s participation in the moon landing as a publicity theme. In the Loeb display windows, relevant displays gave passers-by information about the event.

Museum of Communication, Bern