Mussolini and Switzerland

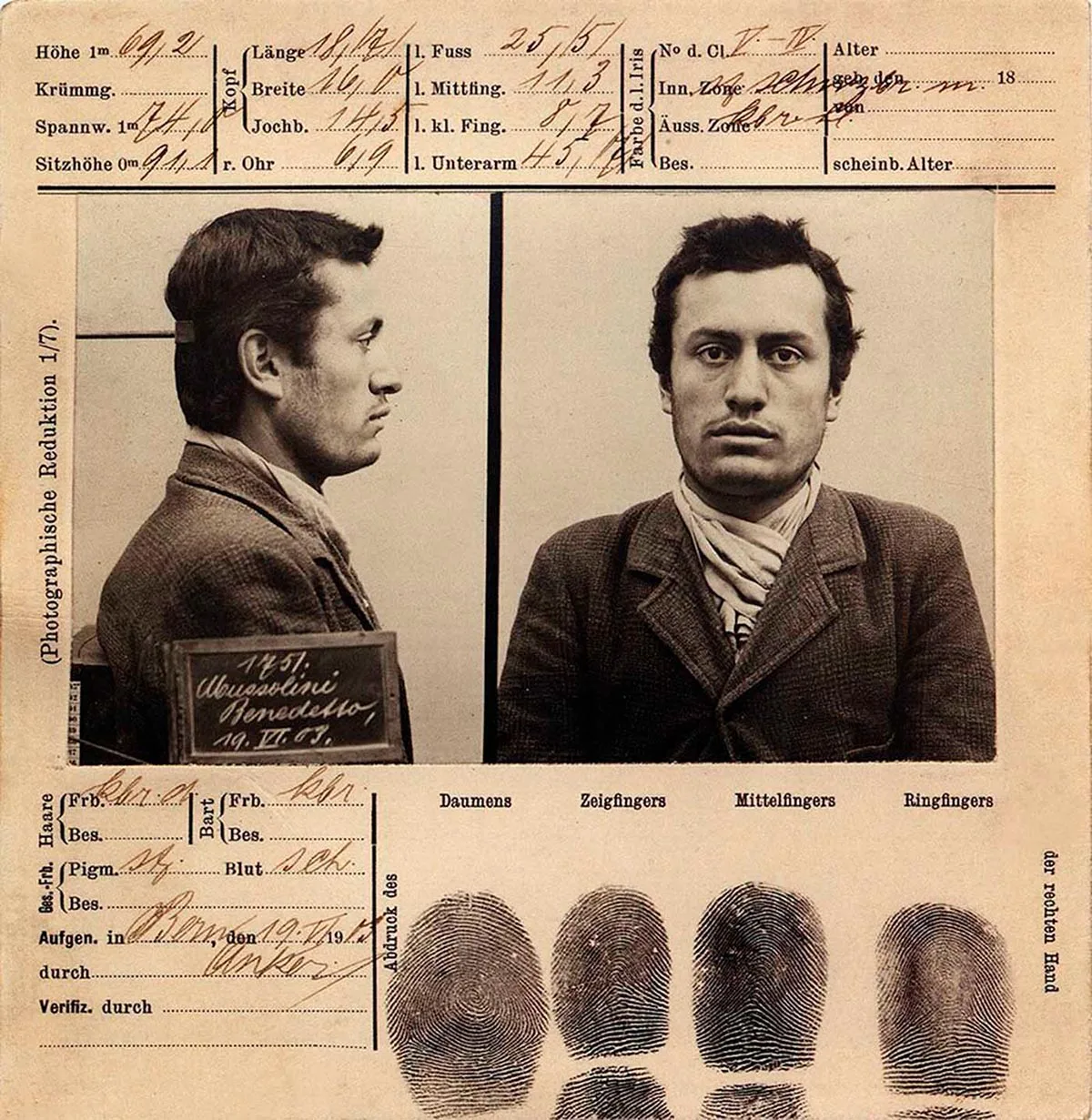

In the early 20th century, Benito Mussolini caused a stir in Switzerland as a rebellious socialist. Some decades later, he became a threat to the country as a fascist dictator.

Sent to prison in Bern

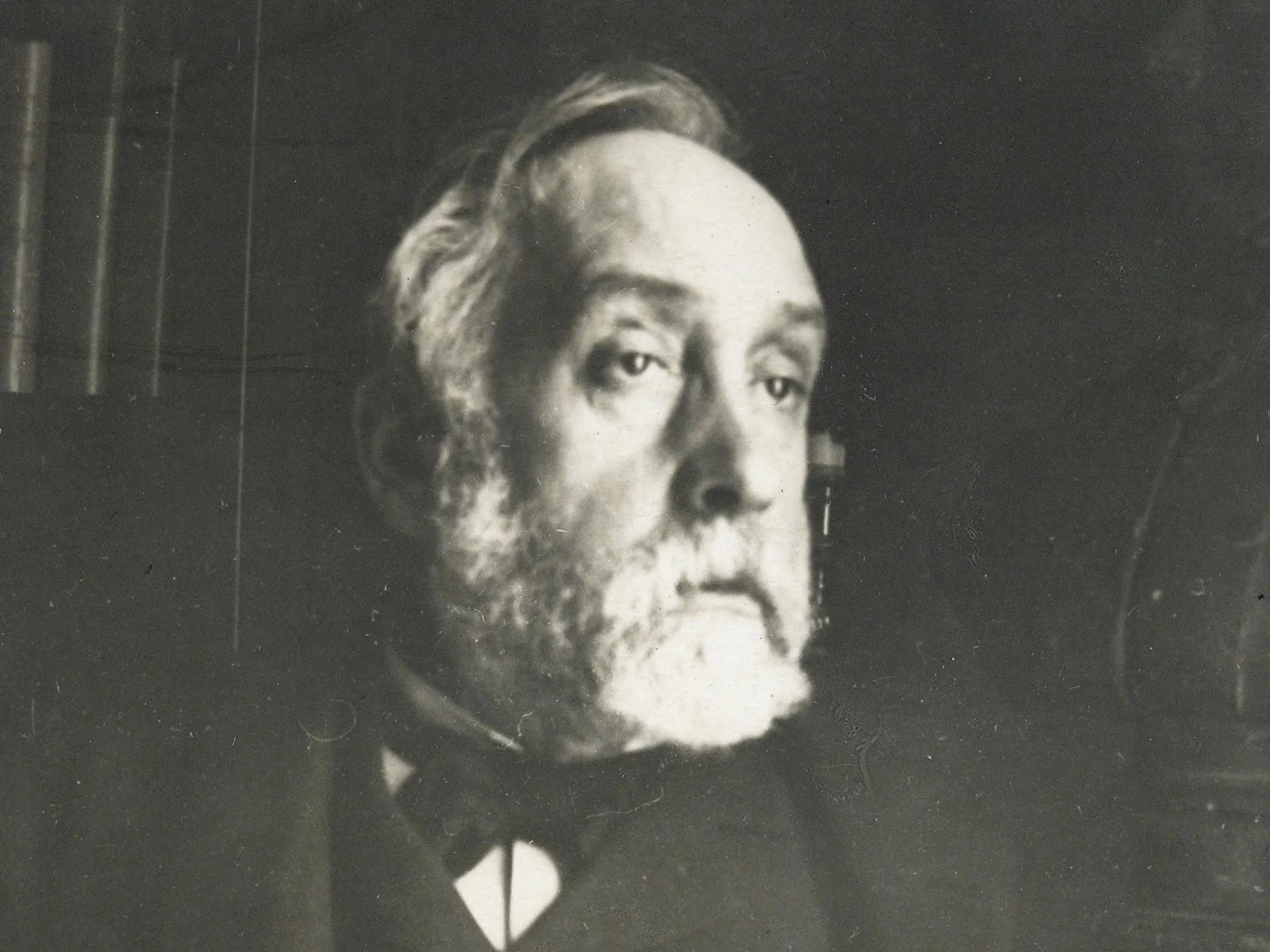

From socialist to fascist dictator

Mussolini flees north towards Switzerland