No right of domicile for Jews

The Federal Constitution of 1848 denied Jews free settlement in Switzerland. Only the signing of a trade agreement with France prompted Switzerland to end this discrimination.

The Swiss Federal Constitution of 1848 was one of the most modern in Europe at the time. But it also brought with it a lot of dross from the past. One of the most obvious inconsistencies with the nation’s middle-class self-image, which was based on equality of all citizens before the law, was Article 41 of the Federal Constitution, which stated that only “Swiss citizens of a Christian denomination” should have an unconditional right of settlement throughout the territory of Switzerland. The information brochure distributed to the Swiss population justified this provision as follows: “The intention here ideally is to exclude the Jews, especially in consideration of the foreign Jews, who would not hesitate to rely on contracts existing between Switzerland and neighbouring countries which stipulate that the citizens of those countries expect to be treated the same as the Swiss.” This meant that the Cantons were at liberty to deny Jews (including those recognised as Swiss Jews) the right of domicile, which most of the cantons then proceeded to do. And since even its own Jews were denied the right to settle, Switzerland considered itself justified in also denying that right to foreign Jews.

At the constitutional review conference in February 1848, only the representatives of the Cantons of Geneva, Neuchâtel, Vaud and Aargau voted against the adoption of this discriminatory article. Even the majority of Switzerland’s “founding fathers” held the simple, unquestioned belief that the presence of Jews posed a threat. The Zurich representative (and first Federal President) Jonas Furrer in particular insisted on this exclusion, and held out the promise of even more restrictive laws against Jews. The representatives of the Swiss Jews, most of whom lived in the two poor Aargau farming villages of Oberendingen and Lengnau, were appalled by this affront: “A senior Federal review committee will allow us to comment that this exclusion is contrary to all expectations and that we know of no reason why this affront should deprive us, even in the newly created Federal Constitution, of better prospects for the future of our young people.”

Differences with France and the USA

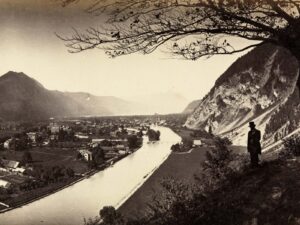

But if Switzerland’s politicians were expecting, with this discriminatory passage in the country’s Constitution, to have conclusively settled their relationship with foreign countries in the matter of establishment issues, they soon found they were mistaken. When Baselland began, in 1851, the process of expelling unregistered French Jews residing in the canton, in order ultimately to ban Jews from living in the canton altogether, France protested on behalf of her Jewish citizens against this “forcible expulsion”. In 1855, Switzerland concluded another trade agreement with the USA, which excluded American Jews from the freedom of domicile in Switzerland; however, this apparent victory for the Swiss position immediately provoked outrage in the USA. The US President personally ordered his ambassador to Switzerland, Theo S. Fay, to prepare a report on the legal situation in Switzerland. Fay submitted that report in 1859. Switzerland did not come out looking good: a Jewish American would have no problems travelling through France or Prussia, “but once he gets to Switzerland, the situation changes. He is regarded as a swindler, a usurer, an enemy, even though he has not come here to do harm to any person. […] If he is not immediately and unceremoniously expelled from the canton by a gendarme, a police officer soon appears, to shower him with abuse and demand an excessive fee.” Some cantons, such as Graubünden, Zurich and St. Gallen, did in fact then drop their restrictions on settlement; however, as long as Article 41 remained in force, no canton could be forced to change its policy on settlement.

France stands firm

By the beginning of the 1860s, Switzerland was finding time had run out on its attempts to include anti-Jewish discrimination in its trade agreements with foreign countries. In 1863, the Netherlands refused to ratify one of those agreements in view of Switzerland’s intolerant stance, and in the same year France refused outright to enter into closer negotiations with Switzerland if it wished to exclude French Jews from the mutually conceded right of establishment. Switzerland’s chief negotiator, Johann Kern, attempted at first to use this point as a bargaining chip against concessions in customs matters, but the French side immediately made it clear that it had no intention of bartering “issues of higher morality” for tariff reductions.

In 1864, the Federal Assembly finally accepted the French terms. This about-face was preceded by heated discussions in which, in addition to the fundamental question of Jewish settlement, issues of cantonal sovereignty were also a hot topic. Federal President Jakob Dubs had appealed to the honour and the economic interests of Switzerland in order to push through the ratification. In the Federal Constitution “this beautiful sentence was uttered: ‘All Swiss are equal before the law’”, but “then we got to Article 41 and breached this principle to the detriment of the Jews. […] If we look at the world around us, we are ashamed to see that on this Jewish issue we are alone, or in company that is almost worse than being alone. We have become the barometer of European society. No nation any longer wishes to enter into an agreement with us in which we denigrate a portion of its citizenry. This position has become untenable without great harm to our honour and our interests.” In response to fretful claims that Switzerland would lose its self-determination if it were to bow to French pressure, Emil Welti, member of the Upper Chamber for Aargau and later Federal Councillor, replied: “One should allow oneself to be pushed towards the true, the good and the right. Free will alone would not have brought us this far; all progress depends upon a thousand others who provide the moral justification, as is the case here.”

With the ratification of the trade agreement with France, French Jews now had rights of domicile in Switzerland which could still be withheld from Swiss Jews as long as Article 41 remained in force. The Federal Council then launched a referendum on the partial revision of the Constitution, with the intention of removing this article. On 14 January 1866, Swiss voters accepted this change with 53% of votes in favour; the results varied substantially from canton to canton. Zurich accepted the revision with 93.9% voting yes, while the worst performer, Appenzell Innerrhoden, rejected it emphatically, with just 2% in favour. General religious freedom and freedom of worship would become reality only upon the complete revision of the Constitution in 1874.