© La Triennale di Milano. Foto: Gianluca Di Ioia

Design as a band-aid for nature

Under the title ‘Broken Nature’, the XXII Triennale di Milano showcases original contributions to the climate debate from the perspective of design, art and applied science.

The title of the XXII Triennale di Milano – ‘Broken Nature’ – sounds dramatic. The catalogue cover features a photo of a greyish glacier draped in cloths to slow down the melting process. The cloths hang tattered and befouled, witnesses to futile and somewhat tardy human endeavour – yet more garbage, the shrouds of the Anthropocene.

Anthropocene is the term used in specialist jargon for the geological era since the Industrial Revolution, which has been characterised by unprecedented human impacts on nature.

For the concept of design, this throws up completely new challenges. At any rate, that’s what the team staging the Triennale believe, especially its director, the architect and urban planner Stefano Boeri, who is known for his ‘Bosco verticale’ forested residential towers, and this year’s curator, Paola Antonelli from New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Entrance to the ‘Broken Nature’ exhibition. Installations: Totems, Neri Oxman and the Mediated Matter Group at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019.

© Triennale Milano. Foto: Gianluca Di Ioia

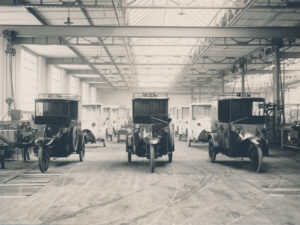

The Triennale is thus following up on its previous claim to setting the tone in the design discourse. When it was first held as a competitive design exhibition in Milan in 1933, the Triennale reflected the spirit of the dawning of the new modernity. Nothing is a more cogent reminder of this than its venue, the Palazzo dell’Arte, financed by a textile industrialist, with its monumental fascist architecture. At that time, the focus was on functionalist design for a better life, albeit as an element of a dictatorial political regime which harnessed the aesthetic for its own purposes.

During the economic boom after the Second World War, the Triennale was an important showcase for leading Italian and international design proponents, until a longer hiatus followed from 1996.

It wasn’t until 2007 that a design museum was opened in the Palazzo d’Arte, and then in 2016 the Triennale was revived. This represented a turning away from an increasingly ambiguous modern understanding of design, which had evolved perceptibly in the direction of an aesthetic of product and industrial design whose primary aim was to fuel consumerism. In a world in which the negative consequences of this consumption are increasingly visible, the modern idea of the ‘good life’ needed to be radically reinterpreted. So the 2016 slogan was ‘Design after Design’.

Coral structures 3D-printed from porcelain as a base for reef growth.

© Triennale Milano. Foto: Gianluca Di Ioia

‘Broken nature’ adds another prong to this reinterpretation. The prelude is eerily beautiful: two colossal screens arranged almost side by side display then-and-now images from the past few decades of massive impacts on nature caused by human action. We see the insane growth of Asian mega-cities such as Shanghai in the last two to three decades, but also the sprawling proliferation of less ecologically varied desert locations such as Las Vegas and Dubai. In addition, there is the retreat of huge glaciers and lakes, and the open wounds left by mining.

Then it really gets going. The five sections of the exhibition present a more or less blunt inventory-taking of this planetary debacle. Alongside all of this, basic investigations highlight individual issues, such as the development of wind currents that is essential for the environment. Centre stage is given to solutions already implemented, along with all kinds of prototypes, and the strategies necessary for their communication and implementation. The Triennale aims to be nothing less than an exchange hub for forward-looking ideas at the intersection of design, urbanism, architecture, art and science.

Plastiglomerates are mineral formations of molten plastic, sand, wood and stone. Collected by Kelly Jazvak in collaboration with geologist Patricia Corcoran and oceanographer Charles Moore at Kamilo Beach, Hawaii, 2013.

Photo: Jeff Elstone. Courtesy the artist and FIERMAN gallery.

Along the concourse, featuring more than a hundred projects, we are brought face to face, for example, with the mass extinction of species, which has called for countermeasures such as the Norwegian ‘Global Seed Vault’ in the Arctic. But at the same time, we discover that this ‘deep-freeze seed store’ for endangered plants is now itself at risk due to climate change and the associated thawing of the permafrost soil layer. We see ‘plastiglomerates’, fossilised concretions of plastic that wash up by the score in countries such as Hawaii, and the fatal consequences of invasive plants. Some examples, such as coral structures 3D-printed from porcelain as a base for reef growth, point towards possible solutions. Others, such as the archive of objects that are mundane today but may become rarities in the future – tree bark, clean water, a handful of fertile soil – challenge the existing idea of the museum. Are we perhaps preserving the wrong things and losing sight of what’s really important?

The main part of the exhibition leaves behind this rather nightmarish chapter, and focuses instead on a broad array of current proposals for solutions. There are examples from the fields of recycling and upcycling, applied mainly to the clothing and furniture sector, as well as everyday objects. The experiments with new biomaterials are also highly topical. Special textiles made from silk, and even bricks made from biomass generated with the aid of mushrooms, are engendering completely new architectural fantasies. But seemingly ‘minimal’ proposals for new food trends that are practicable in the mass market are perhaps more realistic, and thus more environmentally impactful. One example is the 100% plant-based ‘sausage of the future’, created at ECAL Lausanne, which puts an end to the dreariness of tofu. The proposed models relating to the distribution and purification of water also seem more immediately useful. Also encouraging are diverse insights into more local projects around the globe, concerned with the conservation of resources and at the same time the preservation, mediation and revaluation of threatened artisanal knowledge and skills. These micro-approaches ‘from below’ are quite heartening, because they represent a global shift in consciousness.

A view of the exhibition «The Great Animal Orchestra», Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, 2016.

© Luc Boegly

In any case, communication and didactics are the top priority, to drive home the urgency of this shift. Whether it’s detailed research on smartphone recycling or educational games, there’s plenty on offer at this Triennale, and the exhibits are complemented by the somewhat over-staged exhibition ‘The Nation of Plants’, the masterly film installation ‘The Great Animal Orchestra’ created by bioacoustician Bernie Krause, and 62 global contributions on the main theme. Although Switzerland is not represented with a contribution of its own, the Vienna design studio EOOS worked with EAWAG and Swiss firm Keramik Laufen to develop the ‘Circular Flows’ recycling toilet, which was honoured by the jury.

Of course, not everything on show really convinces; some of the exhibits, broadly speaking, replace old plastic with new. And the key issue, that of transferring all these analyses and design ideas into practice, is unlikely to be resolved by an event such as this. It may be feared that initially, the well-known economic and political forces will dominate. But these forces can be influenced. At the very least, the 2019 Milan Triennale provides a host of suggestions and ideas for the necessary turnaround.