Jean-Luc Rickenbacher

The Ticino grotto

A visit to a grotto is a highlight of any stay in Ticino. Enjoying local products and regional dishes under the spreading shade of the trees is an experience not to be missed. What stories could these celebrated stone structures tell?

Back in the days when refrigerators didn’t exist, people had to find other methods for keeping food fresh. In Ticino, food was stored in caves in the rock. This took advantage of a natural phenomenon: due to the differences in temperature, there is a constant flow of air through the caves. The circulation of air means it’s cool all year round in these grottos and the temperature remains constant. Ideal conditions for storing meat, cheese and wine. If there wasn’t enough room in the grottos for all the supplies, the caverns would be hollowed out a bit more or little stone structures would be built outside the entrance. In the open area in front of the grotto, local peasant farmers would install a stone table and a bench. In their rare moments of ease, they sat in the shade of the chestnut trees, had a snack of meats and swapped anecdotes over a glass of wine.

Rock cellar near Cevio in the upper Vallemaggia.

Jean-Luc Rickenbacher

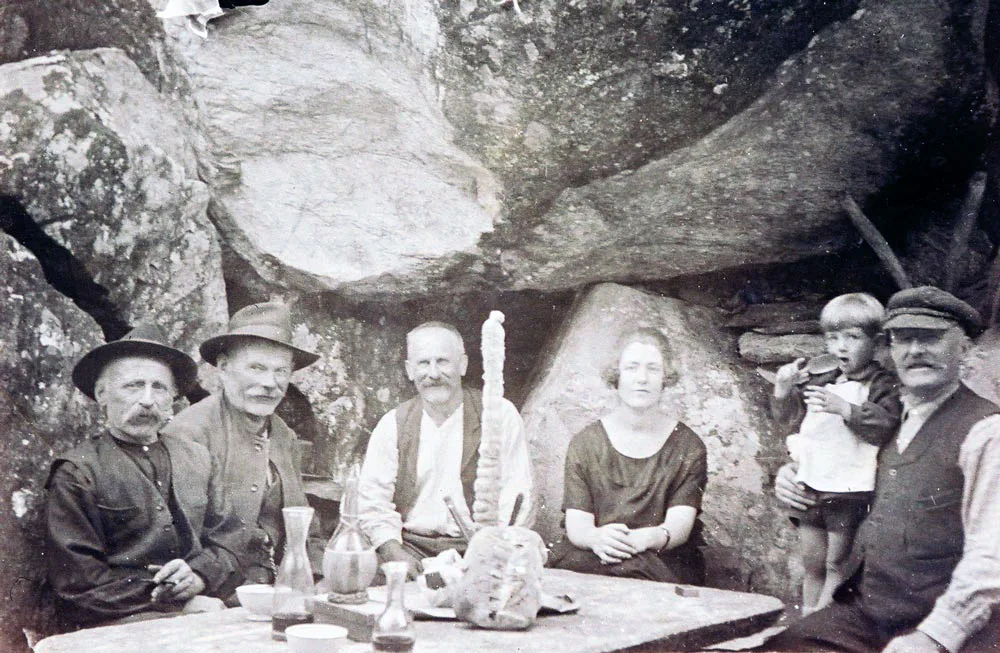

Farmers eating the food they’ve produced.

Dante Peduzzi

Popular places to meet

These larders of yore became important meeting places for the local population. The forecourt areas were enlarged, and the first liquor licenses were issued in the second half of the 19th century. The Grotto Morchino in Pazzallo near Lugano even gets a mention in the 1919 novella Klingsor’s Last Summer by Hermann Hesse, who settled in Ticino after the end of World War I. The people of Ticino traditionally drank their wine from a boccalino. Some specimens of these hand-made and individually painted clay jugs are genuine objects of skilled craftsmanship. The wine was drunk either neat or diluted with gazzosa, a flavoured and carbonated soft drink. The boccia courts that sprang up beside some grottos were also popular. Hours were spent vying to see who could throw their ball closest to the pallino (the little white ball). In addition to animated conversation and lively discussion, many a visit to the grotto had musical accompaniment, with singing or someone playing a mandolin.

Boccalino with two spouts between the handles, made around 1850. Faience, painted, glazed.

Swiss National Museum

Boccia courts outside the grottos in Cama GR, early 20th century.

Dante Peduzzi

An elderly couple sitting on the granite steps of a house in Ticino – the man is holding a boccalino in his hand. The woman, in a headscarf and tattered apron, is using a hand spindle. Photographed by Rudolf Zinggeler-Danioth (1864-1954).

Swiss National Museum

Tragedy on Lake Lugano

But the grottos shouldn’t be romanticised as social gathering places where good cheer and joviality prevailed at all times. Day-to-day life in these communities, which were largely agricultural until well into the 20th century, was tough. The name of the Grotto America in Tegna recalls the emigration of tens of thousands of Ticino natives who left their homeland and headed overseas to escape the widespread poverty and unemployment. Large segments of the population in the border regions sought to supplement their meagre income with smuggling. So in the grottos people also shared their troubles, gave vent to their frustrations, and sometimes had one or two more drinks than they needed. In addition, there are records of tragic incidents that occurred near the grottos. In 1930, the mysterious disappearance of the then head of the border guards at Cantine di Gandria caused a stir. Mario Vaccani decided, after a visit to the nearby grotto, to row to the opposite shore of Lake Lugano; in the night of 29-30 June his boat was found empty in the middle of the lake. No trace of Signor Vaccani has ever been found.

Gandria, early 20th century. Until 1936, the village at the foot of Monte Brè could only be reached by boat or via arduous tracks. The picturesque Gandria still retains its original village character, with steep steps and narrow alleys.

Archivio di Stato del Cantone Ticino

Missing border guard Mario Vaccani (1894-1930) in uniform, with his daughter Maria.

Fabio Masdonati

A group of smugglers waits for nightfall in a grotto in Scudellate (Muggio Valley).

Archivio di Stato del Cantone Ticino

The quintessence of relaxation

After World War II, the increasing prevalence of refrigerators saw a decline in the use of the grottos. As they had lost their traditional function as food storage pantries, they were often left untended. In other cases, people added extra seating to the forecourt area and massively expanded their grottos. Some of the grottos were now indistinguishable from ordinary taverns and restaurants, and they became popular destinations for day-trippers. The boccalini brought back from Ticino as souvenirs were soon well known throughout Switzerland, and the gazzosa soft drinks filled in swing-top bottles are now available in every part of the country. In Ticino and the Italian-speaking valleys of Graubünden, there are a number of efforts to revive the cultural and culinary heritage of the grottos. They have retained their rustic character and these days are synonymous with enjoyment, relaxation and taking things easy.

The wine and the ‘gazzosa’ are enjoyed by young and old.

Dante Peduzzi

Documentary about the grottos with humorous commentary by Ticino writer Sergio Maspoli (1920-1987).

Radiotelevisione Svizzera, ‘Da tempo nostro’, 2 September 1964