Swiss National Museum

The Rütli fan

Bavarian King Ludwig II was a somewhat eccentric monarch. But he was a fan of Switzerland, and of Central Switzerland in particular. He even wanted to buy the Rütli.

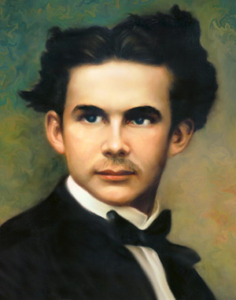

On 20 October 1865, the Hotel Schweizerhof in Lucerne was already quite full. When a traveller from Bavaria asked for rooms for himself and his companions, there were only three rooms left. The Bavarian was given an ordinary room on the fourth floor, and his companions two rooms on the second floor. When the hotel management discovered that the German guest was Ludwig II, the King of Bavaria himself, they were deeply embarrassed and immediately offered the monarch the ‘royal’ suite on the first floor. But the King declined the offer with thanks; perhaps he was also pleased that, for once, his incognito travelling had worked. The young Bavarian King was visiting Switzerland not officially as a state guest, but unofficially, as a private citizen. He had been King for just a year. But he had already tired of the politics. The intrigues in the German Confederation were of no interest to him, and as a result he was rarely seen in Munich playing his kingly role. He much preferred to devote himself to culture.

Historic photograph of the Hotel Schweizerhof in Lucerne. The photo was taken around 1875.

Swiss National Museum

Ludwig was more interested in art than in politics. He was particularly taken with William Tell. He therefore travelled to Central Switzerland in 1865.

After seeing Giacomo Rossini’s opera William Tell, the locations of the Tell epic held a magical attraction for him. Ludwig was something of a quixotic personality type, and had already idolised Tell. As a 15-year-old, he bought a statuette of William Tell out of his own modest pocket money. Three years later he bought the book The Legend of Tell. Now he was 20 years old, and walking in Tell’s footsteps. From Lucerne, the crowned head of state travelled on to Brunnen, where he stayed at the unpretentious ‘Weisses Rössli’, close to the pier. With the Tell book in his luggage, in the following days Ludwig II visited the Rütli, the Stauffacher Chapel, the ‘Hohle Gasse’ in Küssnacht, the principal town of Schwyz, and Seelisberg and Bürglen. He also went three times to the famous ‘Tellsplatte’ or Tell’s Slab, with its Tellskapelle, the old Tell’s Chapel, in which he was particularly interested.

WATER FROM THE RÜTLI SPRINGS

He was just as enraptured by the Rütli, where the Rütli oath is alleged to have been sworn at the confluence of three water sources. Ludwig II knelt there in order to drink from all three springs at the same time. He also climbed up to Seelisberg to admire the view of ‘the mirror of the blissful lake lying far below and the place where a heroic, freedom-loving people swore the overthrow of tyranny’, as he put it in a somewhat turgid letter to Richard Wagner. The King ignored the fact that at home in Munich he tended to struggle with liberal advances of any kind. Instead, he envisioned how he could build a castle at this mythically charged place. The young King expressed an interest in buying the Rütli. That would have been quite something: if Ludwig II had bought the Rütli and built one of his fairy-tale castles on it! His Neuschwanstein Castle, pulling in more than 1.5 million visitors per year, is the most visited travel destination in Germany. But Ludwig was several years too late. The Rütli has enjoyed ‘inalienable national property’ status since 1860, and has been put in the care of the Schweizerische Gemeinnützige Gesellschaft (Swiss Society for the Common Good) for administration.

The Tell myth not only made an impact on the King of Bavaria, but has also been cited or depicted in artworks time and again all around the world, as in this painting by Anton Zucchi.

Swiss National Museum

Neuschwanstein Castle in a photograph dating from 1886 or 1887. It was built for Ludwig and is an idealised medieval castle.

Wikimedia

Ludwig also had another vision for the Tellsplatte, whose mystical story he loved just as much as that of the Rütli. For the Tellsplatte, he envisioned the construction of a gigantic statue of Tell. He planned for this statue to be on such a huge scale that the big steamships would be able to pass between its legs. But this idea too came to nothing. The Bavarian King wanted at least to be involved in the restoration of the paintings in Tell’s Chapel on the Tellsplatte.

In addition, Uri natives attempted to foist on the Bavarian King the Wirtshaus Tell, a tavern in Bürglen – they called it the ‘original home of William Tell’, although nobody could say that with any certainty. They were asking 100,000 francs for the tavern, which for the rates at the time was a vastly overinflated price. Negotiations with the innkeeper, Franz Epp, were already well advanced when the abrupt arrival of dismal October weather drove the monarch out of Switzerland. The sale fell through, but at least Ludwig left with some landscape paintings of Uri scenery, painted by Jost Anton Muheim, in his luggage.

Print of Bürglen. The work was produced in 1825.

Swiss National Museum

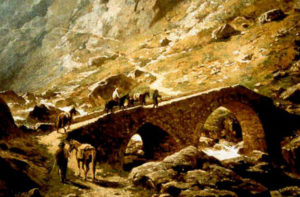

Painting of the Häderlis Bridge over the River Reuss, by Jost Anton Muheim, around 1890.

Wikimedia

A DESIRE TO BE AN HONORARY CITIZEN OF URI

In the course of his contacts with people from Uri and Schwyz, the monarch had mentioned in passing that he would be very pleased to be granted honorary citizenship ‘by the Cantons of Schwyz and Uri’. But the Uri government baulked. On 5 March 1866, 12 Uri citizens submitted a petition. They requested that Ludwig be granted honorary citizenship ‘in view of his truly noble disposition towards the original Switzerland and his proven especial veneration of the founder of our liberty, Wilhelm Tell’. The petition was signed by, among others, Bürglen innkeepers Franz Epp from the ‘Tell’ and Anton Lauener from the ‘Adler’, the politician Anton Müller and the landscape painter Jost Anton Muheim, who had sold Ludwig his paintings – the initiators were thus all people who would profit by him. The Zuger Volksblatt newspaper considered the proposal to be very unrepublican: ‘We see in it a fawning play for royal favour – perhaps for filthy gold and gifts!’

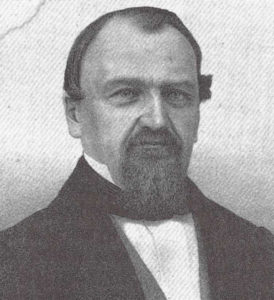

But before the Landsgemeinde (cantonal assembly) was able to discuss the request, Federal Councillor Jakob Dubs intervened: foreigners should only be given honorary citizenship if they renounced their existing citizenship. Well, it was unthinkable for a Bavarian king to renounce his citizenship of his own country, so the Uri petitioners withdrew their petition after the intervention from Bern. After 12 days in Switzerland, the Bavarian King returned to Hohenschwangau. He had thoroughly enjoyed his trip: ‘I was enraptured.’ He was less enthusiastic about the people, however, as he wrote in one letter: ‘Regrettably, the people there are not as ideal as the wonderful country. – They are indeed pious, worthy and industrious, but completely lacking in special talents, without the merest impetus of the intellect.’ Officially, however, the Bavarian King lied, diplomatically writing to the Schwyzer Zeitung newspaper: ‘The memory of my visit to splendid Central Switzerland and the honest, free people, which may God bless, shall always be dear to me. Yours in esteem, Ludwig’

Portrait of Federal Councillor Jakob Dubs.

Wikimedia