Swiss National Library

The lost film of Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein

90 years ago, Russian director Eisenstein shot a film at La Sarraz Castle featuring an array of avant-garde luminaries. But the footage has remained lost to this day.

Russian film-maker Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein was famous for his motion pictures such as ‘Battleship Potemkin’ (1925) and ‘Ivan the Terrible’ (1945). In 1929, Eisenstein was permitted by the Bolshevik government to travel to Western Europe to find out about and study innovations in the world of film. When he arrived in Zurich with his cameraman Eduard Tisse and assistant Grigori Alexandrov, he was invited by Hélène de Mandrot, a top patron of the louche artistic community, to visit her estate – La Sarraz Castle in the Canton of Vaud.

The lady came from the upper-class Revilliod-de Muralt family of Geneva, and was much talked about as organiser of the Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne (International Congresses of Modern Architecture), in which Le Corbusier was a notable participant. Each year she organised artistic and intellectual get-togethers. In 1929, these events were devoted to the independent film industry. As a result, the first Congrès international du cinéma indépendant (International Congress of Independent Cinema) was held in the depths of the Vaud countryside. Eisenstein was interested in meeting other film directors, and accepted the invitation. From 3 to 7 September, he spent several days at the medieval estate with filmmakers from various countries.

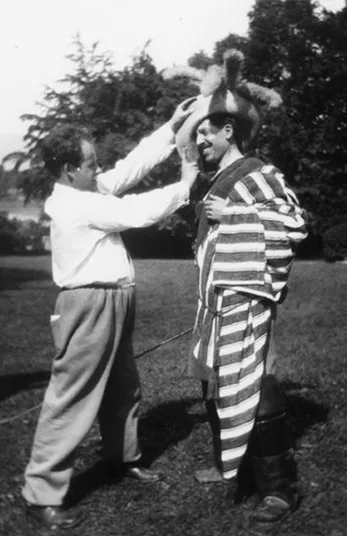

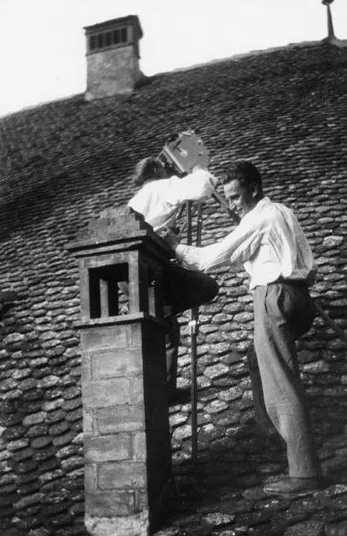

During that time, which was for the most part devoted to the art of eating, the artists developed a project to show their gratitude to their hostess, deciding to shoot a film at the castle. They wanted to use the unique setting of the building in their film, and even brought out the motley assortment of old junk that lay forgotten in the castle’s attic. Obviously, their opus needed a name: the piece was christened ‘The Storming of La Sarraz’, an ironic allegory of the struggle between independent and commercial cinema, and was an allusion to the common topics of conversation in society circles. The task of turning this cinematic lampoon into reality was given to Eisenstein. First of all, he cast the roles: Hungarian writer Béla Balázs was to play the army commander of commercial cinema, novelist and historian Janine Bouissounouse took on the role of the fading spirit of free cinema, the French writer Léon Moussinac acted the part of D’Artagnan, and Eisenstein himself played the army commander of independent cinema. But Madame de Mandrot’s other guests were not left out – Jack Isaacs, Hans Richter, Walter Ruttmann, Fritz Rosenfeld, Mannus Franken and Moichiro Tsuchiya also made appearances in the film.

As a witness to the day, Pierre Zénobel photographed the little group and the rouged and painted actors; his photos, which are held by the Swiss film archive Cinémathèque suisse, prove that the film was actually made. The troupe included a Japanese man, Hiroshi Higo, who was likewise a filmmaker and a Communist, and was also involved in the project. It was he who, for reasons unknown, took the film with him at the end of his stay and returned with it to Tokyo. Hiroshi Higo was known for having produced a number of avant-garde films in Japan before the First World War, and showed the film to his party under the new name ‘Kokusai Dokoritsu Eiga Kaigi’.

Madame de Mandrot (centre) during an architectural convention at La Sarraz Castle, 1928.

Sergei Michailowitsch Eisenstein, 1935.

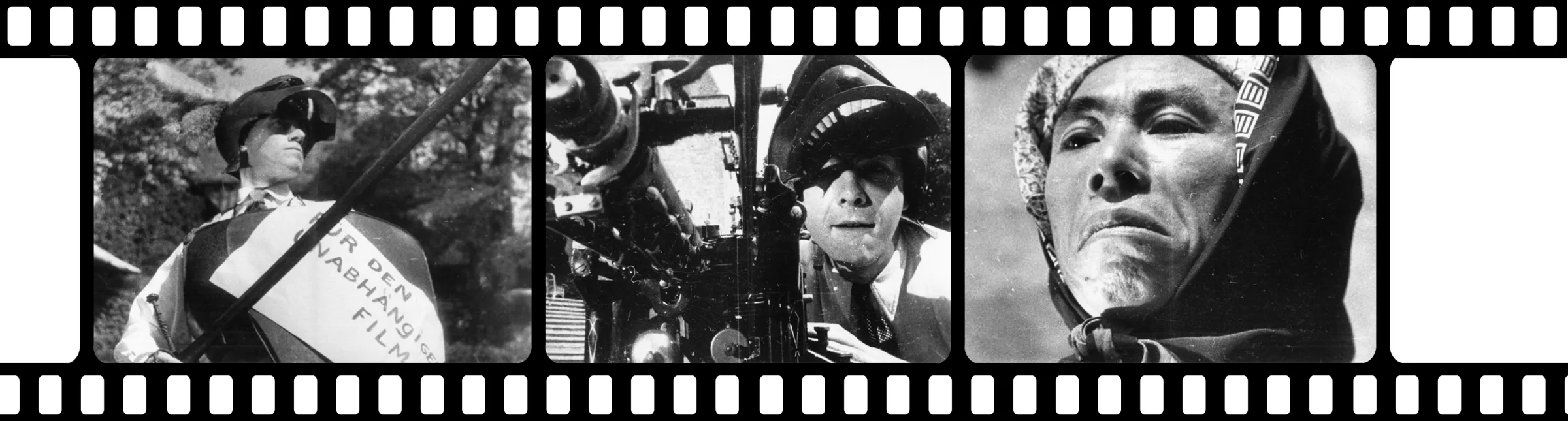

As a testimony of the day, the designer Pierre Zénobel (1905-1996) photographed the event at the Castle.

Collection of the National Film Archive

In 1930 Tokyo was in the Taishō era, the Russian model had spread and there had been real political parties in Japan for about ten years. In 1922 the Japanese Communist party, Nihon Kyōsantō, was created. In 1926, with government support, two new, more moderate workers’ parties were established: the Rōdōnōmintō (workers and peasants’ party) and the Nihon Rōnōtō (Japanese workers and peasants’ party). At the same time, fascist movements grew and spread like an evil plague; these included the Kokuhonsha, founded in 1924, which counted among its members many military personnel, but also professors and public servants. Faced with this worrying development, the government set up a new organ of repression, a kind of Gestapo: a special higher police unit called the Tokkō, which immediately began to persecute Communists and active labour unions.

Against this backdrop, on 13 June 1930 the film shot by Eisenstein in the Canton of Vaud was screened for members of the Communist party at a soirée put on by the proletarian Japanese film society – after the police had instituted special security measures. However, the film did not make it through the censor’s net. It was placed on Japan’s censorship blacklist under number E 7612 – proof that the film continued to exist for at least a while longer. Even though the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo still holds that inventory number, the film has been lost for decades.

Photographs of the filming.

Collection of the National Film Archive

All searches by experts, mainly those carried out by the representative of the Soviet film review board, Kazuo Yamada, who was appointed by Gosfilmofond – the Russian agency responsible for the central archives of Russian film – have so far yielded nothing. As a result some people believe today, despite the photographic evidence held in the Swiss archives, that the film never existed. Nor is it known whether Eisenstein ever talked about the film after his return to the USSR, or preferred instead to keep quiet about the fact that he had been the guest of a Swiss aristocrat.