© Yves Saint Laurent, photo: © Sophie Carre (2019)

Yves Saint Laurent as ambassador for Lyon silk

Soie ou saucisson – in the traditional Lyonnaise families, you belonged to either the silk camp or the sausage camp. Both have left their mark on the city’s economic development. Visitors to the Musée des tissus in Lyon can now discover what links the silk camp with the renowned fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent.

Eighteen and a half metres of mauve silk mousseline, various other fabrics for lining and making up, ninety hours of work: these are the rough data for an Yves Saint Laurent evening gown from his final haute couture collection in 2002, now on display in Lyon. These details were recorded by his studio on a ‘fiche’, an index card, together with his pencil sketch of the design to be made up and a small fabric sample. You stand awestruck before this Botticelli-like creation. Then your gaze wanders to the other visitors to the exhibition who, like you, are wearing more or less cheap clothes from today’s mass-produced lines. Something functional with sneakers. You can look to the heights of Olympus, and then turn your head and stare into the abyss of a discipline called ‘fashion’.

This abyss concerns the crisis that overtook the European fashion and textile industry in the 20th century, after it had triggered the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. This crisis has deepened since the 1990s, with the relocation of production to low-wage Asian countries. But there has been a change in society’s perception of fashion as well. Who still slavishly checks for the ‘Made in France’ label before shelling out, as the fashion-conscious rushed to do again after World War II? These days, street style is king. At the same time, socio-political and environmental objections are getting louder. The concept of fashion, devised in 17th-century France for the purpose of stimulating the economy, and having now culminated in the ostensibly democratic phenomenon of cheap fashion, fosters exploitation and a throw-away mentality. Who is paying for it? Is the concept not generally out of date?

The magnificent display of Yves Saint Laurent’s work at Lyon’s Musée des tissus, founded in 1864 and now housing one of the most important collections of its kind in the world – well worth seeing in its own right – doesn’t directly address these questions in the current exhibition. But when presented with the haute couture of the great fashion designer, a fairy tale from another time, those questions can tend to go through one’s mind. Especially in this place, in the city of the silk weavers and their uprisings against exploitation. A place where the innovative Jacquard loom (on display in the Museum), with its punched cards which both predated and anticipated the principle of modern computer programs, was invented. The idea of this invention was to make not only manual operation, but also rebellious workers, unnecessary.

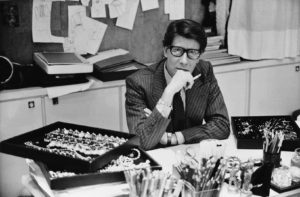

Yves Saint Laurent in his office on the Avenue Marceau in Paris, 1986. Photographer unknown.

© All rights reserved

The questions about the profound change in the fashion and textile industry arise indirectly, through the subtle design of the exhibition, which combines the sensual pleasure of an impressive number of exquisite dresses and gowns from YSL, as he is known for short, with a very revealing look behind the scenes of their production. This mostly avoids the cult of personality, most likely to be felt when the conversation turns to the importance of the sensory effect of the material for Yves Saint Laurent. Even when choosing the fabrics and during the first fittings, it was important to him to work with live models with whom he was familiar, rather than lifeless mannequins. From the beginning, he was concerned with the interplay of fabric, person and movement.

‘I see fabrics, and out of that comes the idea for a dress,’ the twenty-year-old is claimed to have said. As a teenager in his hometown of Oran (Algeria), he experimented with paper dolls. From his mother’s fashion magazines, he acquired detailed knowledge of the major players on the Paris fashion scene at the time. You stand dumbfounded before his carefully labelled ‘poupées’. They demonstrate the instinctive self-assurance with which the young Saint Laurent worked, catapulting himself into the centre of the Parisian fashion scene as it blossomed again after World War II. At first he worked as an assistant for Christian Dior, from whom he took over after the latter’s early death. Even the earliest examples show what an excellent illustrator he was. Later designs confirm this: a few crudely drawn lines, as unconstrained as they were assured, and the direction his atelier principals were to take in producing an initial design, which he then refined further, was much clearer than that of many of his peers.

A view of the exhibition ‘Yves Saint Laurent. Les coulisses de la haute couture à Lyon’.

© Musée des Tissus Lyon / Pierre Verrier

Selected examples are used to show the complex interactions in which he engaged with his suppliers. With Lyon’s silk industry he had a genuinely symbiotic relationship. The fashion house was indirectly co-financed by this industry; the haute couture, photographed by exclusive photographers such as Claus Ohm, functioned as more than just an advertising vehicle for the cheaper (prêt-à-porter) clothing lines and perfumes, cosmetics and accessories from the fashion designer. Alongside the name of Yves Saint Laurent, the key industry magazines printed the names of the fabric suppliers. That was the very best advertisement these silk companies could have hoped for. Of course it was a bit misleading, because you could hardly order the sample shown. Certain designs were produced exclusively, in precisely limited yardage, for the couturier alone.

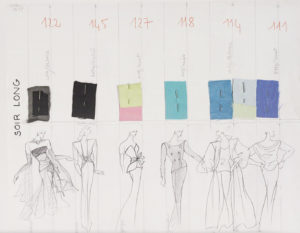

Model sketches by Yves Saint Laurent with fabric samples, 1985-1991 (facsimile).

Swiss National Museum

There was an intricate ping pong going on behind the marketing symbiosis. In the extremely limited time of one season, mini fabric samples, designs and colour charts were tossed back and forth between the textile manufacturers and the atelier chiefs, the principal dressmakers and the couturier himself, who made all the decisions. The middlemen in all of this were dealers, who had no weaving mills themselves, but instead acted as brokers. Among these dealers, the Zurich firm Abraham was able to establish a prominent position in Lyon, thanks to the close relationship between its proprietor Gustav Zumsteg and Yves Saint Laurent. In addition to a perfect overview of the specialities and novelties of the different textile suppliers, Zumsteg’s trump card was his specific knowledge of the couturier’s tastes.

A little cloud of melancholy hangs over all this sumptuousness. A fashion designer working with the costliest fabrics and delicate floral patterns like an artist with a palette: that’s fitting for a feudal society with appropriate occasions on which the sometimes operatic creations can actually be worn. Better to treat them like works of art right from the outset. In fact, Yves Saint Laurent was aware of that himself. He had already marked some of his creations on the studio index card with the note ‘Musée’. This referred to the in-house documentation of his works, out of which the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Paris has since been created.

In a somewhat one-sided way, the focus on Saint Laurent’s special relationship with Lyon silk production highlights the fashion designer’s sensitivity to material textures. However, his exceptional status in fashion history in the 20th century is due at least as much to his sensitivity to social issues. His truly pioneering creation was the trouser suit for women, flattering the androgynous female image he favoured. This is less in evidence in Lyon. But what is clearly highlighted is the concept of haute couture as a highly sophisticated form of textile marketing. Like any good marketing, it relies on palatable, pleasantly quaffable narratives. That is still valid, even if today the narratives, and the channels by which they travel, are very different. Fashion marketing now happens in social media – and in the Museum.

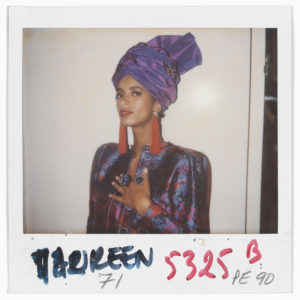

Dress, worn by Natacha. Collection haute couture, Autumn/Winter 1992.

© All rights reserved, Yves Saint Laurent

Ensemble, worn by Ann-Fiona Scollay. Collection haute couture, Spring/Summer 1990.

© All rights reserved, Yves Saint Laurent

Yves Saint Laurent Les coulisses de la haute couture à Lyon

Musée des tissus, Lyon

until 8 March 2020

Hinweis: Texte zur Ausstellung nur auf Französisch und Englisch.

Anyone interested in the history of drapery in art should also pay a visit to the extensive special exhibition ‘Drapé’ at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon (until 8 March). The Musée des Confluences presents the most outlandish headgear from around the world, with a unique exhibition by Antoine de Galbert (until 15 March).