ETH Bibliothek, Image Archive

How the NZZ advanced the cause of polar research

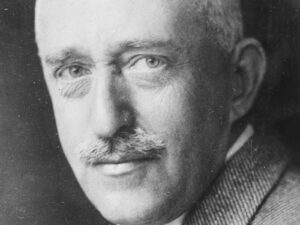

Alfred de Quervain’s Greenland expedition is still celebrated as a pioneering scientific accomplishment. But it’s not generally known that his adventurous journey was only possible thanks to the NZZ.

Anyone who, like Alfred de Quervain, ventures into a dangerous world of ice and snow has to put up with a lot of other people’s opinions. Friends in Zurich warned him about the risks of his journey into the ‘terra nullius’; an expert from Greenland called his plan ‘foolhardy’ and the attempt to carry it out ‘certain death’. But the explorer’s struggles began long before he even set foot on the wasteland of white – namely, with the funding.

A polar expedition calls for substantial sums of money. de Quervain kept his budget calculations as tight as he could, but still came up with a figure of 30,000 francs which, based on historic wage trends, would be about a million francs today. The arduous journeys there and back, the cargo, the provisions, the specialist equipment including sleds and dogs, the support team – all of it had to be paid for. In other countries, the government usually pitched in with funding for the large number of polar expeditions that took place around the turn of the century. For example, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II subsidised the Gauss expedition to Antarctica to the tune of one million Reichsmarks. There was a logic to this. These research expeditions were more than just pioneering acts of scientific achievement; the desire to conquer the forces of nature in the farthest-flung corners of the world also reflected a national obsession and spirit of competition. Alfred de Quervain saw his expedition explicitly as ‘Swiss’, and earnestly claimed that ‘our love of high mountainous regions, our familiarity with snow and glaciers, and a certain adaptability and lack of ostentation, make us uniquely capable of working in the polar region’.

The Swiss flag was hoisted at the highest point of the expedition.

ETH Bibliothek, Image Archive

STRIKING A CHORD WITH THE EDUCATED MIDDLE CLASSES

In August 1911, he wrote to the Federal Council asking the Swiss Confederation to provide 10,000 francs in funding for his Greenland expedition – ‘after millions have been raised for such purposes abroad’. However, the federal state government, having already shown some interest in his cause, rejected his application in November, citing the depleted government coffers. Nor could de Quervain apply for the federal government’s travel bursary because, strangely, that stipend only funded biological research. Still, the Federal Council did grant de Quervain, who was employed as an assistant at the Swiss Meteorological Institute, a holiday from April to October 1912, if the expedition went ahead.

Because the state cried off, private backers were then sought. So ETH professor Carl Schröter, director of the Zurich Society of Natural Sciences, one of de Quervain’s networkers and supporters, knocked on the NZZ’s door. In a letter dated 7 December 1911 to Ulrich Meister, chairman of the administration committee, he played up the ‘rare opportunity’ to secure ‘everlasting glory’ for the prominent newspaper company: ‘It would be a patriotic act of the utmost enormity if your establishment could see its way to acting as a patron of science in this cause.’ German and American newspapers had already done the same. Just four days later the administration committee, including editor-in-chief Walter Bissegger, unanimously decided ‘for the sake of science to make a considerable offering in the name of the NZZ’. de Quervain received 10,000 francs (converting to around 340,000 francs today) – a third of his budget – which constituted one tenth of the NZZ’s profits that year. In return, the newspaper secured ‘a prior claim to all official reports and communications from the expedition’, as set down in a contract. The costs for the telegraphic transmission of communications were borne by the NZZ, which believed that exclusive ‘original reports’ would find a ready audience among the educated middle classes.

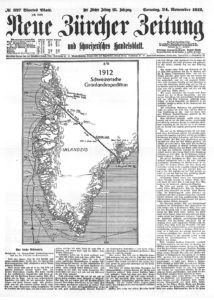

Front page of the NZZ of 24 November 1912 on Alfred de Quervain’s Greenland expedition.

NZZ Archive

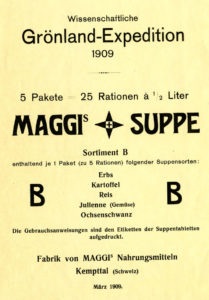

Maggi was a sponsor on the earlier 1909 expedition. In 1912 the company replicated its involvement.

Nestlé Historical Archives

From April 1912, de Quervain reported on key stages of the heroic journey. After his return to Switzerland he also published, extensively and usually prominently on the front page, a series of immensely readable reports, not without a bit of false modesty: ‘We didn’t […] think it would become a feature article.’ With its commitment, the NZZ on the one hand adeptly catered to the polar fever of the time, but also created an enormous breadth of response for it, as historian Lea Pfäffli states in her instructive study ‘Das Wissen, das aus der Kälte kam’ (The knowledge that came in from the cold).

SPONSORSHIP AND SLIDE SHOWS

With appeals for funds in the paper, de Quervain was able to attract additional backers well before his departure date. For example, his estate includes a letter dating from January 1912, according to which the firm Maggi had found out about the expedition’s plans from the NZZ and wanted to provide the explorers with bouillon cubes. It required ‘only a sign from you, and we will provide you with the necessary supplies’ – a sign which de Quervain happily gave. The same goes for condensed milk from the Berner Alpenmilchgesellschaft, chocolate from Lindt, Lenzburg jams and tinned meat, watches from Jura and skis from sporting goods shop Dethleffsen. de Quervain stole a march on today’s marketing practices: he was sponsored, and in return he made favourable mention of his sponsors in his reports and in his subsequent book – product placement under the aurora borealis.

But without government funding, it wasn’t enough to cover the expedition costs. Another key source of revenue at the time was the talks he gave in Switzerland and abroad after his trips, at which slides were shown. With innumerable presentations on Greenland, Alfred de Quervain alone earned more than 5,000 francs. But even with the contributions from the NZZ, other private individuals and scientific societies, and despite ‘great personal sacrifices by the participants’, in the end there was still a shortfall of around 3,500 francs. Due to the ‘expansion of the programme’, extra costs totalling almost a quarter of the original sum had been incurred, as de Quervain complained to the Federal Council at the end of 1913. This time the Council was generous, and had the required amount transferred by the National Bank. And the NZZ, which had made the expedition possible in the first place with its injection of cash? For the time being, it refrained from any further major commitments – ‘first, because the newspaper has of late published travelogues on a large scale […], and then because the financial situation is not encouraging’.

Greenland 1912

Swiss National Museum

06.02. – 18.10.2020

In 1912, Alfred de Quervain trekked across Greenland. The data collected by the Swiss explorer on the seven-week expedition are still of great value for science today. The exhibition examines de Quervain’s pioneering feat in the eternal ice, and links it with the present. Switzerland still carries out glacier research in Greenland, making a significant contribution to one of the most crucial issues of our time: global warming.

Presenting himself as a polar hero was important for Alfred de Quervain, to keep his sponsors happy.

ETH Bibliothek, Image Archive