Swiss National Museum / ASL

Of photographers and hairdressers

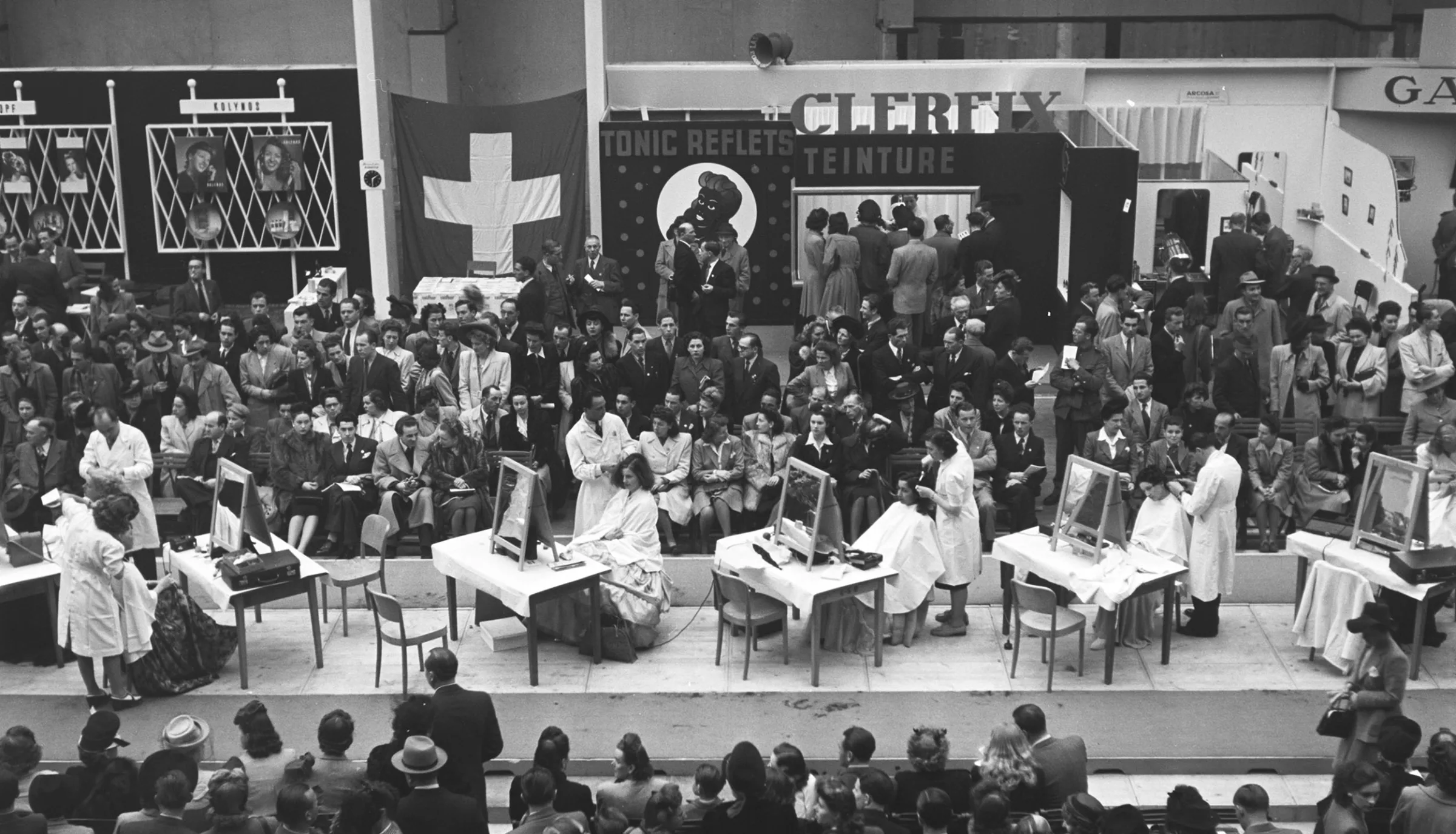

There was a time before mobile phones, a time when press photographers were the eyes of an entire nation. Many of the images they captured are now forgotten. Among them are the many-layered photographs of Switzerland’s national hairdressing competition of 1946.

The Swiss hairdressing championships of 1946 were to be a special occasion, as the first national competition since the war. And what the Lausanne organisers put together on that 7 and 8 April was a truly dazzling programme of events: in addition to the competitions, there were also hairstyle exhibitions and fashion shows, trade fair stands, film screenings and, of course, food and beverages. On both days visitors were invited to a tea dance, complete with live orchestra. The organisers also pulled off a very special coup with an appearance by a Parisian celebrity: the local press proudly reported on world-famous master hairdresser René Rambaud, who honoured this battle for the title with his presence.

For the press photo agency Presse Diffusion Lausanne, this was reason enough to send a photographer to cover the event. His name is unknown to us today. Neither the agency itself nor the magazines that published the photos gave the names of their photographers in those days – that was the standard practice. This namelessness also reflected, to some extent, the desired way of working: emulating legendary German photojournalist Erich Salomon, the professional photographer aimed to be a ‘fly on the wall’ – to document world events from as close as possible, but to remain unnoticed and unobtrusive.

The photographer catches himself in the picture.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

In those circumstances, a photograph that brought its creator out of anonymity – at least out of his visual anonymity – was a surprise. Positioned just slightly too far to the left to remove himself from the picture, the photographer captured his own image reflected in the mirror. From this we learn that our picture-taker turned up dressed for the occasion. And that he worked with a Rolleiflex, a twin-lens medium format camera that was very popular among press photographers of the day. The advantage of this design was that having the photographer looking down through the waist-level finder was often perceived by the person being photographed as less threatening than having a conventional viewfinder aimed directly at them.

A customised exterior and discreet technology were strategies to capture images that were as far as possible unposed and natural-looking, despite the snapper’s physical proximity to his subject. At the hairdressing championships, the competitive environment was of course also well suited to this undertaking. The stressed and flustered competition entrant and his model clearly had better things to do than pause and ‘say cheese’ for the camera.

Rolleiflex medium-format camera with shoulder strap from the collection of the press photo agency Actualités Suisses Lausanne.

Swiss National Museum

The press photo agency ASL

Actualités Suisses Lausanne (ASL) was founded by Roland Schlaefli in 1954, and until its closure in 1999 was the leading press photo agency in western Switzerland. In 1973, Schlaefli also took over the archive of Agentur Presse Diffusion Lausanne (PDL), founded in 1937. The holdings of the two agencies comprise approximately six million images (negatives, prints, slides). In the broad range of subjects covered, there is a focus on federal politics, sport and western Switzerland. The agency opted not to take the step into the digital age. Since 2007, the archives of ASL and PDL have been held by the Swiss National Museum. The blog presents, in a loose chronology, images and photo sequences that particularly stood out when the collections were being recatalogued.

The lack of subjects focusing on the camera helped create a very multi-layered photograph. The people depicted are all looking in different directions. As a result, when looking at the picture our gaze is constantly shifting and refocusing: on the smooth mirror surface our eyes slide from the photographer to the hairdresser’s model, and from her to the hairdresser – only to zero in, a short time later, on another entrant and his model in action beyond the mirror. The double framing by the edge of the mirror and the image border results in all the people appearing only as fragments: they are cut horizontally or vertically, or even twice or three times.

The fact that, even with repeated viewing, our gaze still roves anxiously back and forth may be because in this fragmented world, we’re not seeing a glimpse of ourselves. We’re not in the place where we normally see ourselves: in the hairdresser’s mirror, enabling us to watch, movement by movement, how our appearance changes. According to the hosts of the 1946 competition, such a transformation should always aim to let the customer remain him or herself, whatever the fashion. Whether that was also a criterion when the competition entrants were required to recreate a hairstyle from the court of Louis XVI cannot be answered here. Perhaps this challenge was intended simply to remind those vying for the title who, according to the popular adage, should be their queen: their clientele.

If you wanted to become Switzerland’s champion hairdresser in 1946, you had to master the art of past epochs. One of the challenges was to recreate the extravagant hairstyle of the Princess of Lamballe (1749-1792), lady of the court of Marie-Antoinette. In the end, hairdresser Philipp Walter from Bern finished in fifth place.

Swiss National Museum / ASL