3D in the 19th century

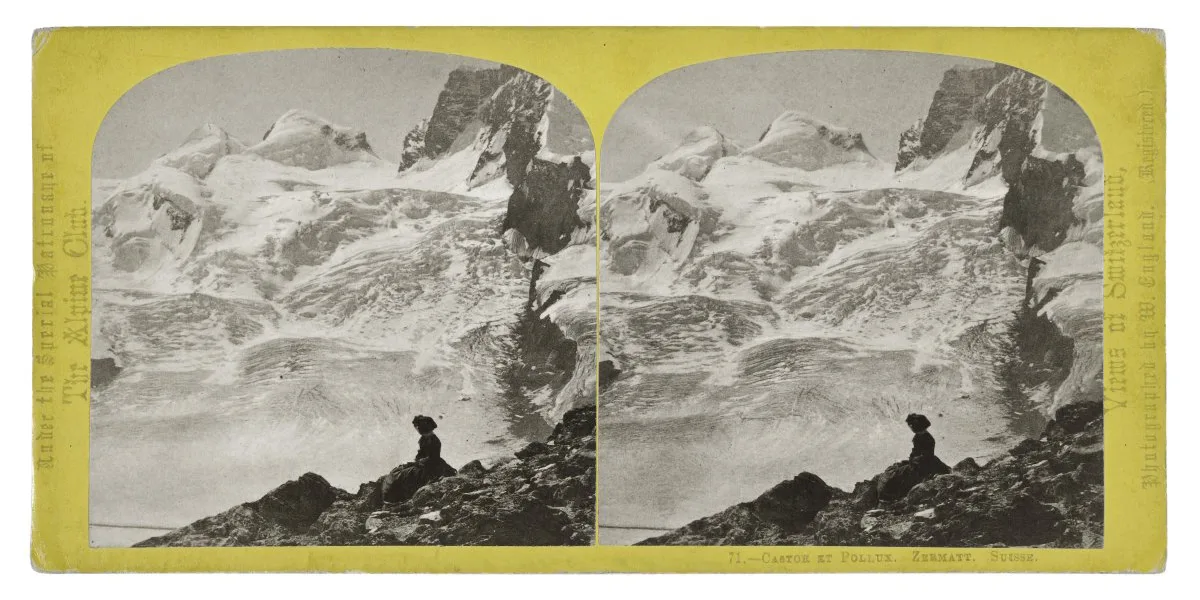

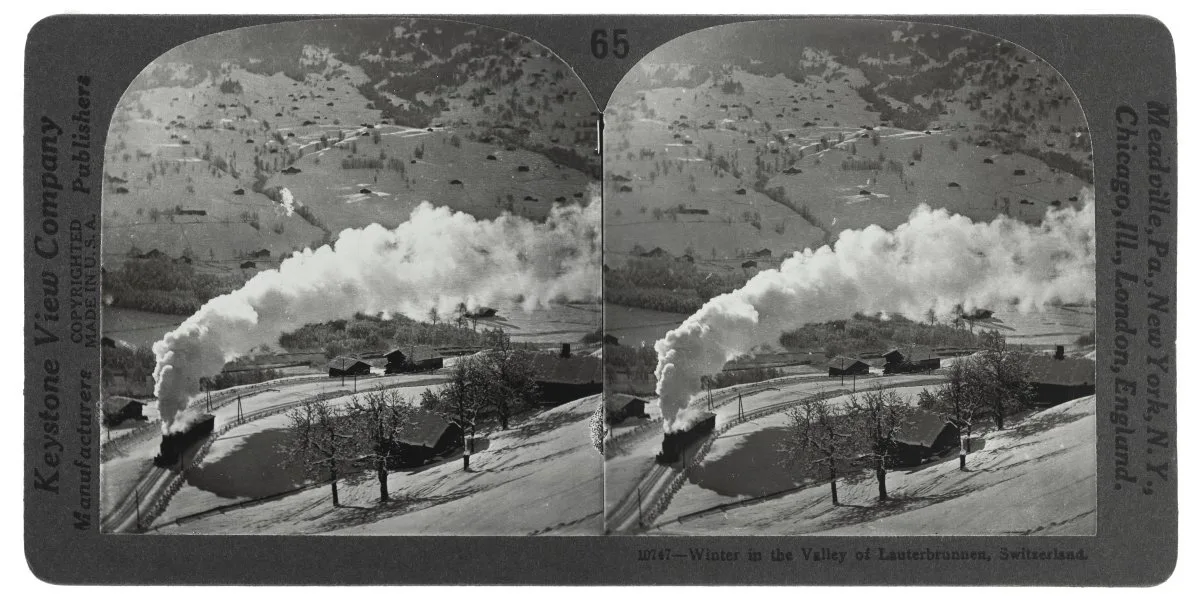

Stereoscopics, the three-dimensional depiction of two-dimensional images, captivated viewers across the globe in the 19th century. And the phenomenon helped to cement Switzerland’s status as a highly desirable tourist destination.

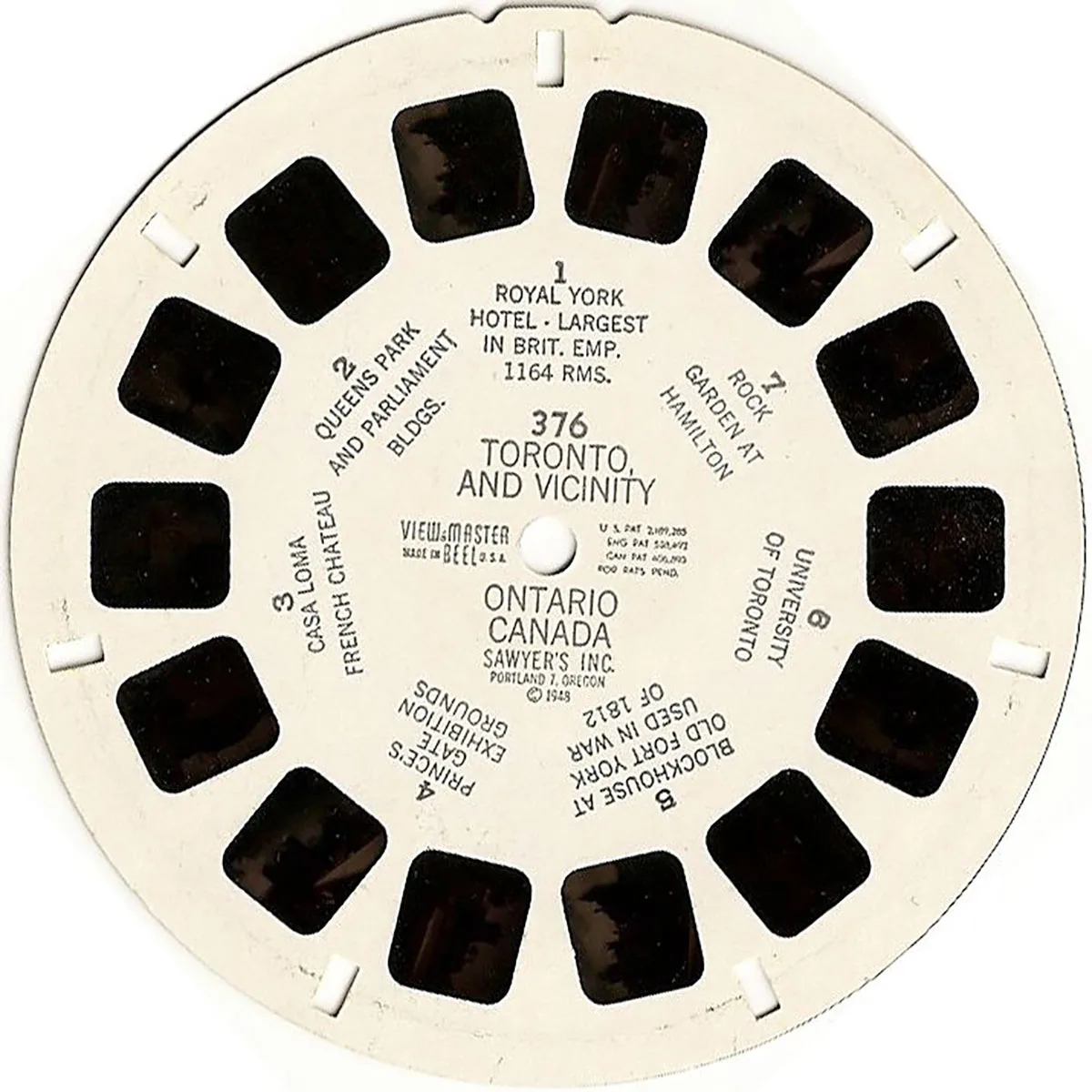

ViewMasters and discs like these were hugely popular in the 1960s and 1970s. Wikimedia

Global mass medium