Resistance and vanity

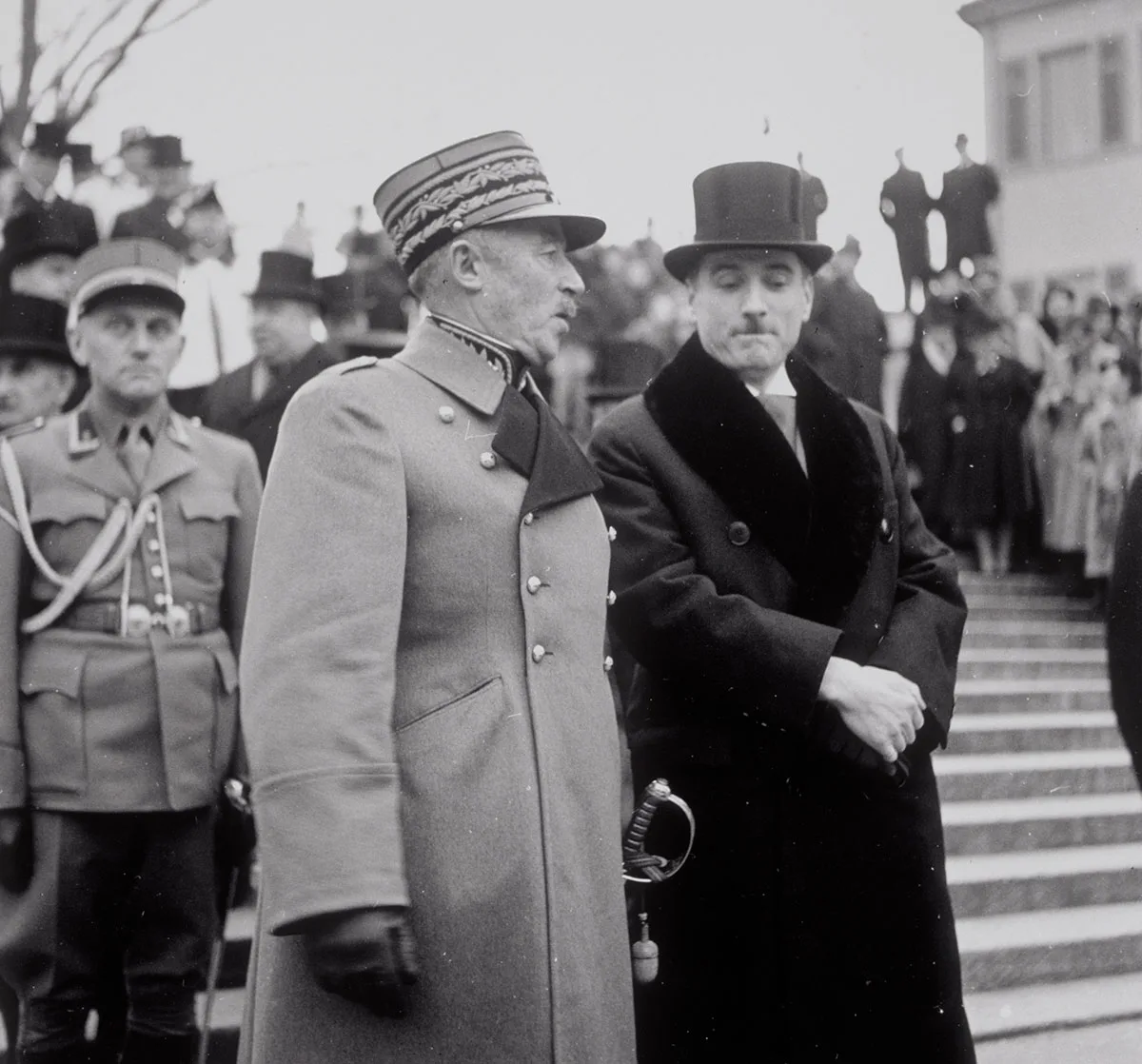

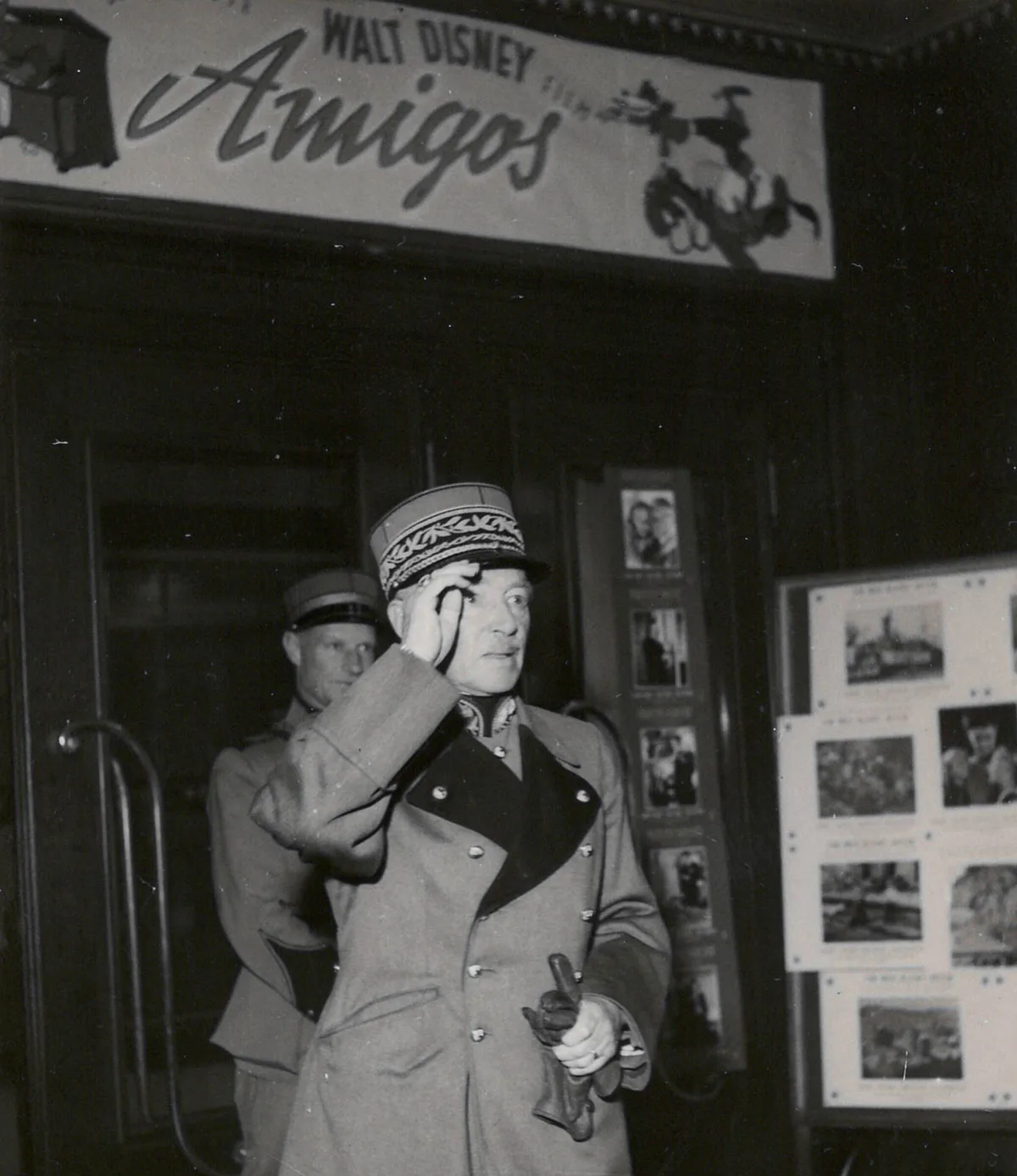

As a general, Henri Guisan led Switzerland through World War II. His public image alternated between resistance and diligent personal propagandisation.

In cinematic footage too, care was taken to ensure the staging sent the right messages. Movie in German. SRF

The General’s secret diplomacy

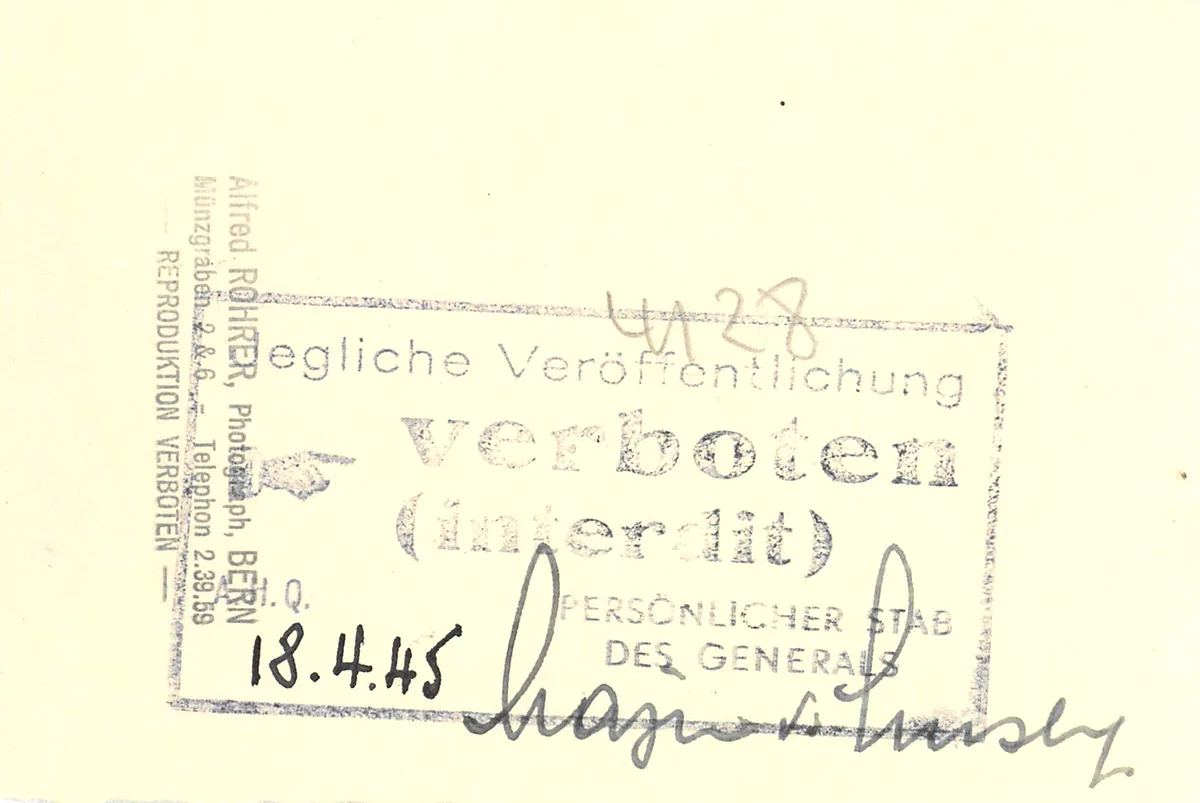

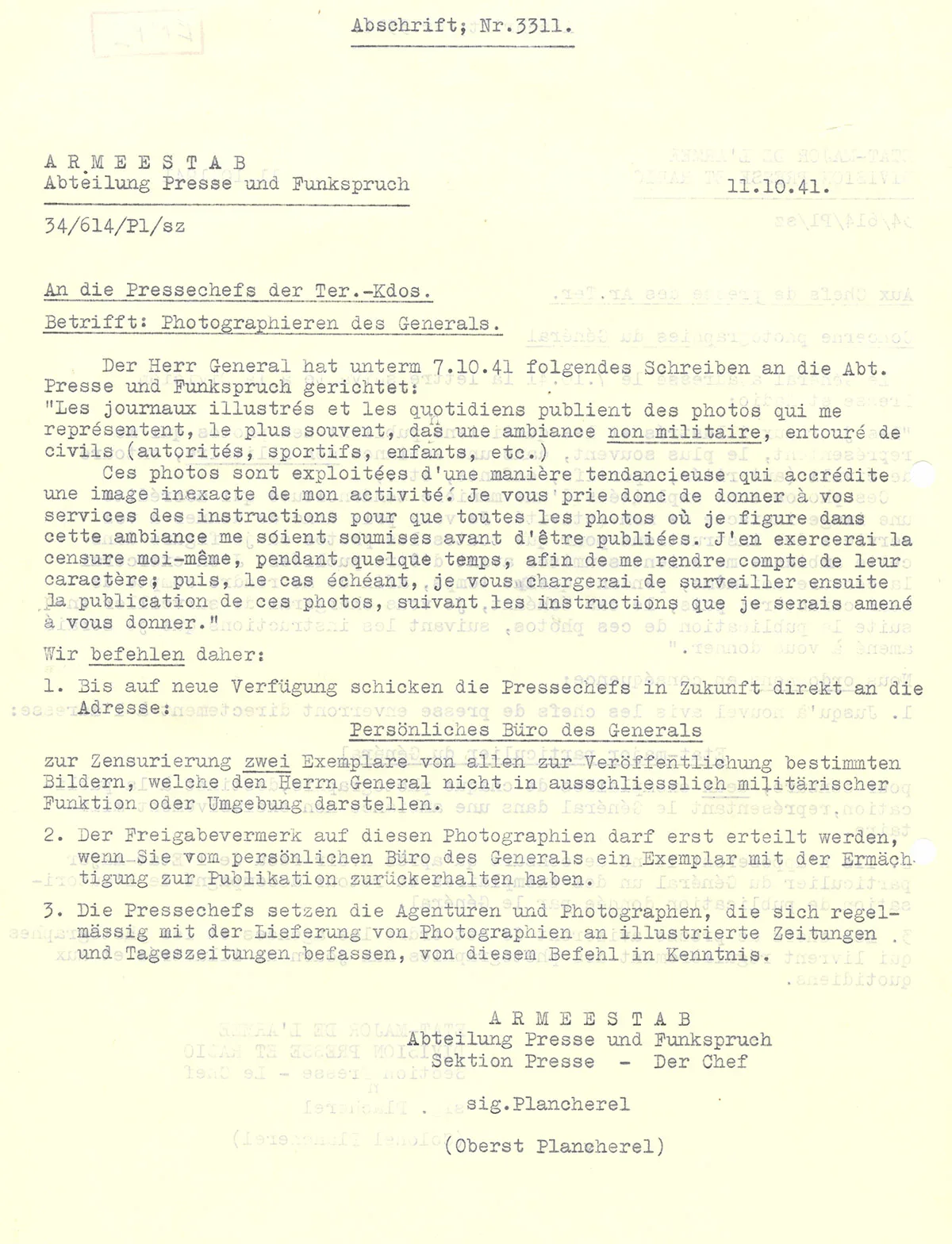

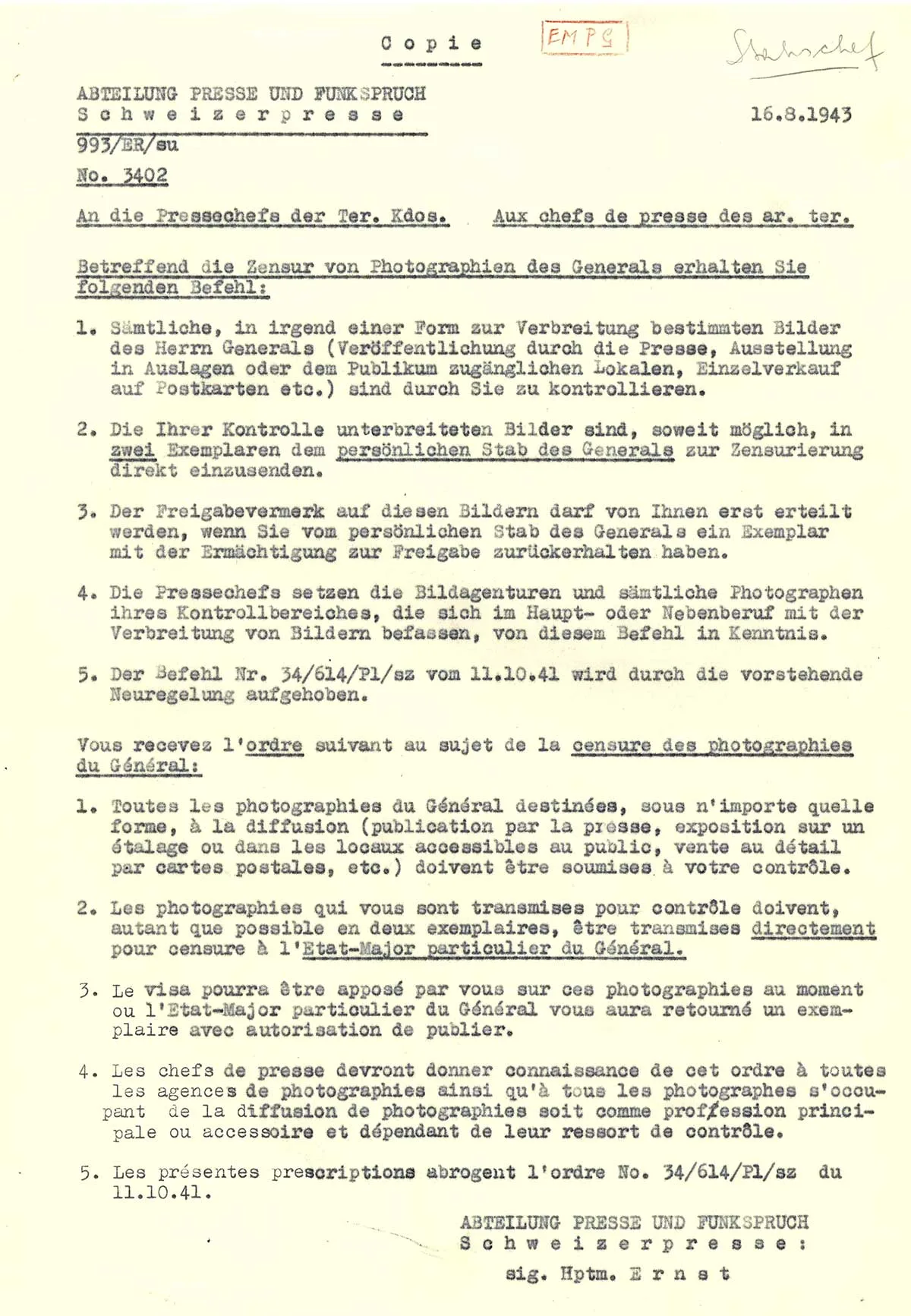

There was also a little bit of propagandisation