Uprising in the convent

From today’s perspective, it seems unthinkable that nuns would rebel, put up violent resistance and ignore ecclesiastical regulations. But during the reform efforts in the 15th century, this was not an unusual occurrence.

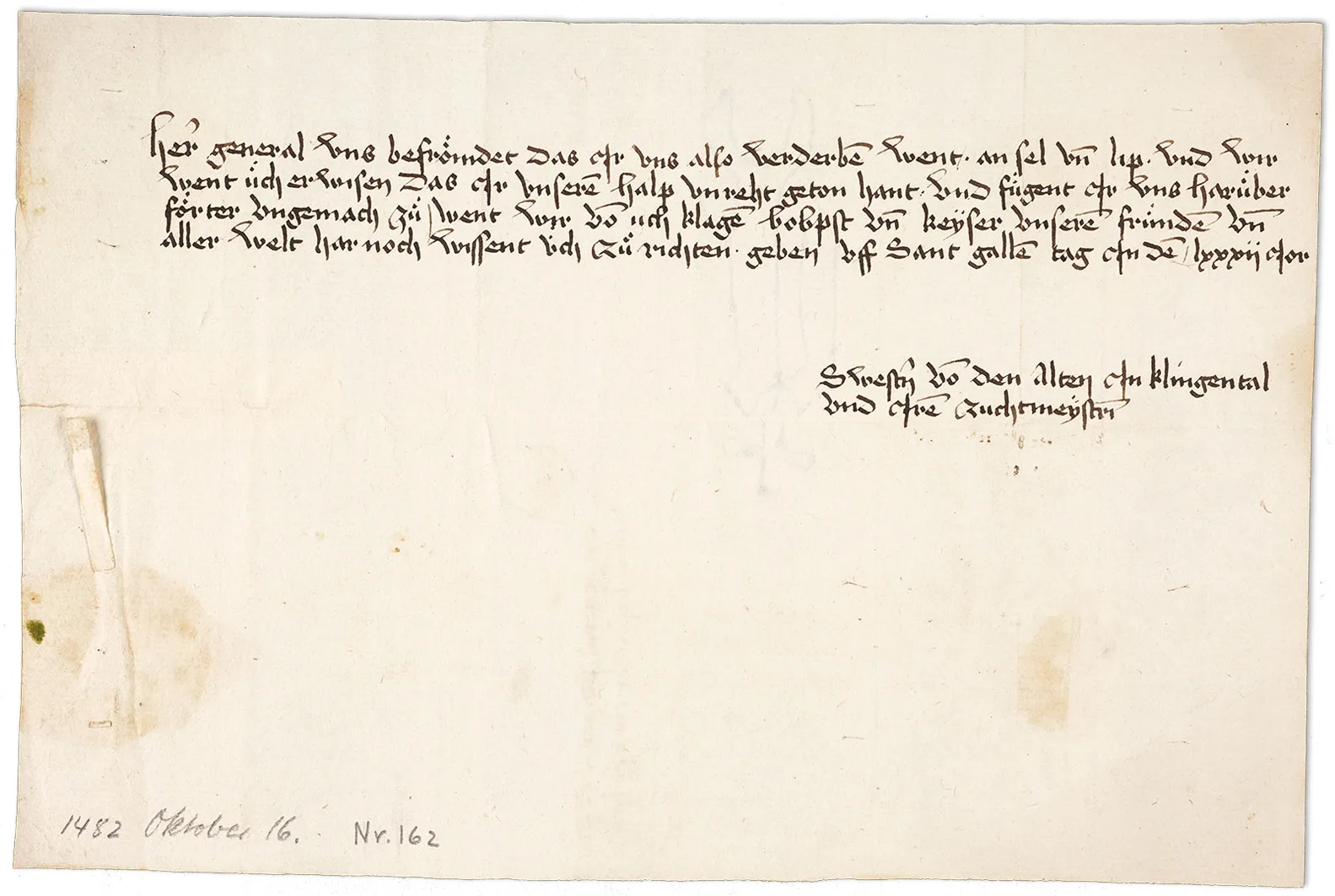

The pope orders an investigation

The "shameless women" move out of the convent

Reforms

As the 14th century drew to a close, a wave of reforms aimed at monasteries and convents took hold, starting in Italy and spreading to the Dominican religious houses in German-speaking areas in particular. The aim of the reform was a return to the original ideals of the monastic life, strict adherence to the rule of the order, and a cloistered life of poverty and contemplation. In Basel, the first monasteries and convents had been subject to reforms since 1420. In many places, and often even within the same house, the reform efforts resulted in two divided and quarrelling parties: those opposed to reform, and those who supported it.