Deprived of a voice

Too young, too foreign, too different? Fifty years on from the introduction of voting and electoral rights for women, the issue of political participation is still a hot topic. A historical overview of disenfranchisement in Switzerland.

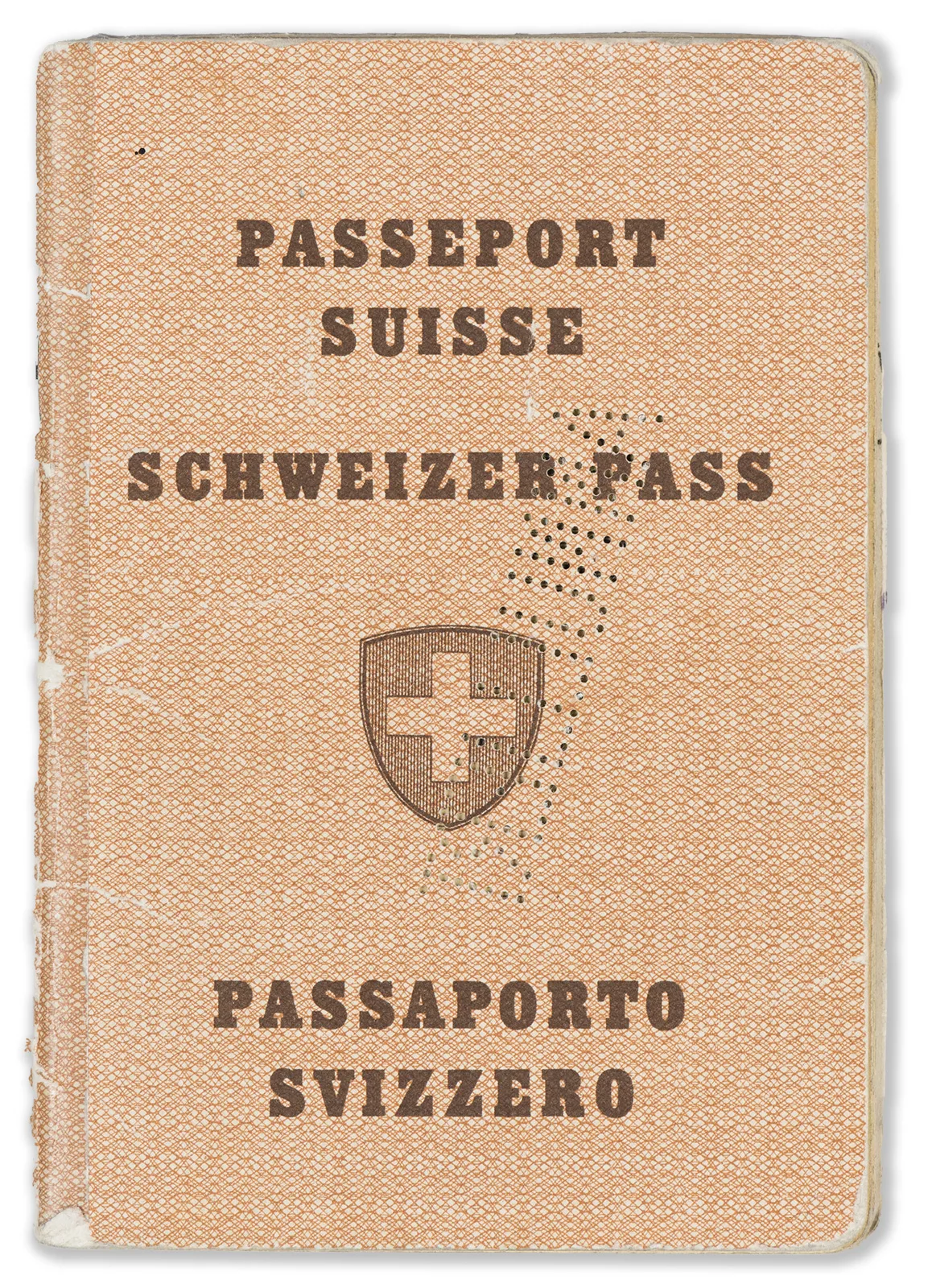

No vote without a passport

No voting by minors

No vote for the mentally disabled

Who in Switzerland is allowed to vote? Explanatory video by ch.ch chchportal / YouTube