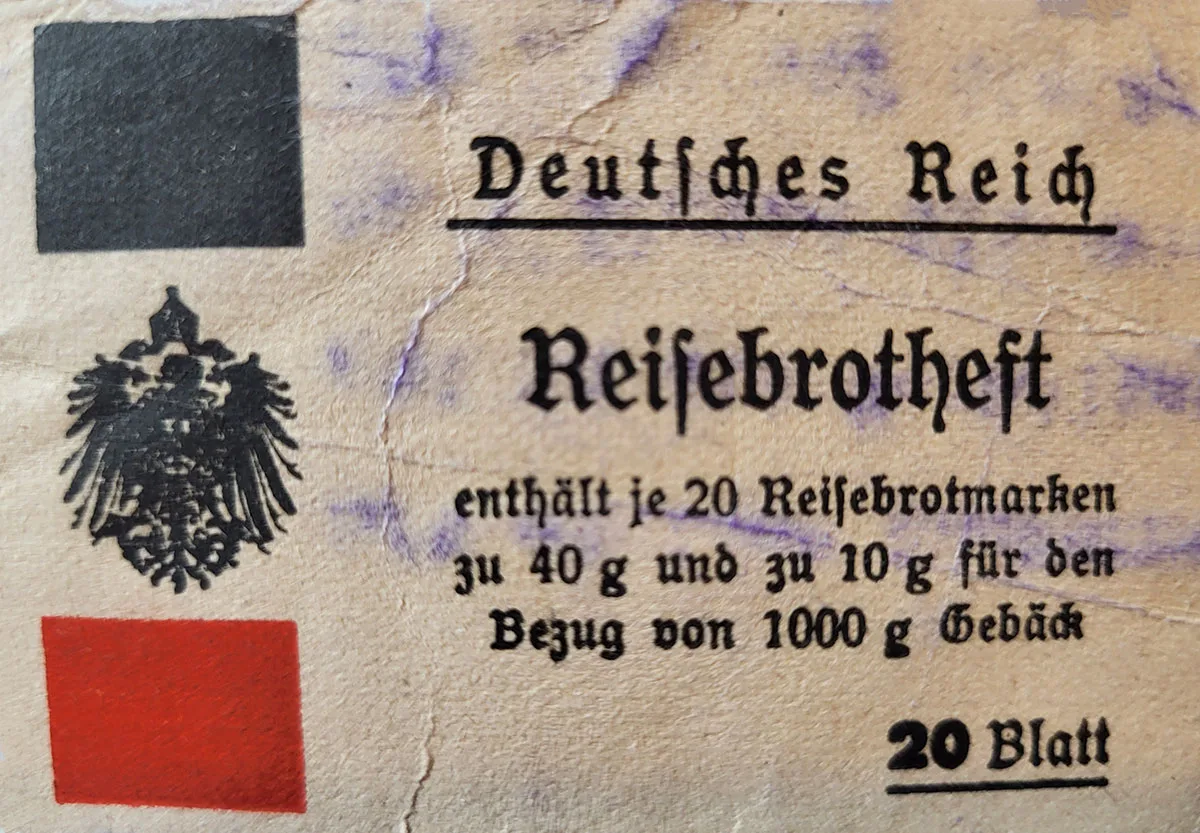

Travels in Germany during the First World War

Despite the dangers, Jean Bucher, boss of a Swiss manufacturer of agricultural machinery, travelled to Germany several times during the First World War. With him he carried his travel diaries, in which he impressively captured daily life in a country at war.

…besides the female tram guards, there are now female train guards too…The daily wage for female rail staff is 2.50 Deutsch Marks plus war allowance.

Everyone fled to the basement. A shower of bullets rained down on the atrium window. The detonations were audible, sometimes loud like a barrage, then dying away, and then all of a sudden, a loud noise that caused the building to shake.