Illustration: Marco Heer

Arguing, swearing, beatings

What’s the link between a vicious domestic brawl from the 17th century and a modern-day comic book?

It’s all kicking off in this 17th-century front parlour. Armed with a big wooden spoon and a grilling iron, a man and a woman, probably a married couple, are laying into each other against a cosy domestic backdrop. The wife has grabbed him by the ‘fighting arm’ to stave off the blows with the grill, while at the same time striking at him with the wooden spoon. Her spouse, meanwhile, is trying to free himself from her grasp, and aims a kick at her.

Violence in couple relationships, like violence against children, is a form of domestic violence which back then, as today, unfortunately, caused enormous suffering. In the light of this problematic issue, it’s therefore difficult to see any element of comedy here – even though that was probably the intended effect of this round pastry mould dating from the late 17th century. The image itself, and one small detail of the depiction, show that this scene of violence around 1700 was made rather as a ‘humorous’ exhortation to married couples to live together peaceably.

Baking pastry goods such as gingerbread or aniseed cookies in various shapes is a Swiss tradition dating from the 15th century. On high days and holidays, for instance, meals always included breads and pastries decorated with figures relating to the theme of the particular occasion. At baptisms and weddings, congratulations, hopes and even admonitions were conveyed with moulded puddings and sweet dishes. In addition to the subjects of love, wedded bliss and being blessed with children, weddings would feature visual exhortations to coexist in peace. The bond between man and wife should be lived as a community and a partnership and should not end, as depicted on the pastry mould referred to above, in a ‘conjugal war’.

Round wooden pastry mould featuring a vicious domestic brawl, around 1690.

Swiss National Museum

MALE DOMINANCE

The fact that, in the 17th century, a vicious domestic argument could be considered ‘funny’ and at the same time serve as an exhortation is based directly on the prevailing view, at that time, of married life between men and women. The Reformation to some extent created new rules for public, religious and private life. The way the world worked was clearly geared towards the patriarchal order, enshrined in law and increasingly subject to state supervision. Put simply, the world was ordered as follows: as God the Father rules over humankind, the people are under the control of the authorities (aristocracy) and the head of the household (pater familias) reigns over the family and the servants. In that spirit, the husband was given ‘righteous’ dominion over the family, in which the wife was required to take a subordinate role. This ‘male dominance’ also extended to disciplinary authority, which allowed the husband to exert a ‘corrective’ influence on the behaviour and habits of his wife with, among other things, beatings.

The same was not true for women. Thus, in addition to the exhortation, for the contemporary observer this scene of marital conflict may also have had an amusing function: an enraged man who tried to assert his claim to power by dealing out a beating and was rewarded with the same by his wife would be seen as a laughing stock.

Two women flogging a monk, pen and ink drawing by Urs Graf, 1521. The man’s pain is illustrated by his facial expression and a gaping head wound.

Fine Arts Museum Basel

FIRST COMIC ELEMENTS?

One little detail in the depiction deserves special attention. This is the small five-pointed star, shown at the woman’s eye level. It could be a mimetic, or representative, pictogram, a reference to the person’s inner state. These days, the interpretation of the star as a ‘pictogram indicating state of mind’ in scenes like this is strongly influenced by the use of this sign in comics and cartoons. In cartoons, for example, the symbol is associated with pain or drunkenness. People are said to be ‘seeing stars’. Could this star be just such a visual ‘set phrase’? The visual arts of the Middle Ages and the modern era captured pain in facial expression and gestures, but also in the depiction of physical effects of trauma, such as injuries or wounds inflicted. Adding a star as a symbol of pain would tie in with the more ‘humorous’ message conveyed by the scuffle on the pastry mould. A different perspective could also point to another emotion in the woman: she is ‘stärndonnerswild’ (so enraged, she’s seeing stars). According to the dictionary of Swiss dialect Schweizerisches Idiotikon, there is evidence of this adjective in use in Switzerland in the 17th century.

Another interpretation of the star could also be that it indicates a curse word uttered. Expletives such as ‘Himmelheiligstärnewält!’ or ‘Stärnedonnerwätter!’ were common swearwords, and still are, explains the Idiotikon. Undue swearing was punished by the authorities. In addition, it would certainly be indecorous to present such a verbal lapse on a sweet pastry served to mark an occasion such as a wedding. This too can be compared to swearwords in comics. In the medium of comic books, sweary rants are often represented by strings of coded characters, especially if the intended readership is mainly children and teenagers. For similar reasons, the carver of the wooden mould may have been restricted to the pictogram, and the interpretation left up to the knowledgeable 17th-century observer.

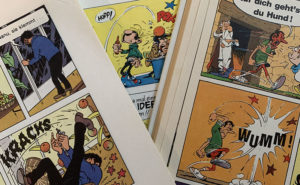

In comics, stars often symbolise pain or represent a swearword.