The White Plague

Today coronavirus is spreading fear, alarm and uncertainty – 100 years ago, it was tuberculosis and the Spanish Flu that cut a deadly swathe through Switzerland.

Exactly 100 years ago, Hans Castorp was sent to Davos for a course of treatment at the health resort. He had tuberculosis, and in the high-altitude sanatorium there he encountered a bourgeoisie weary of civilisation, people who cultivated ennui and wallowed in their own suffering. They played patience, listened to chamber music, tended to their stamp collections, and stuffed themselves with cakes and chocolate. The introspective world of these sanatoria enclosed a strange ‘mixture of death and amusement’.

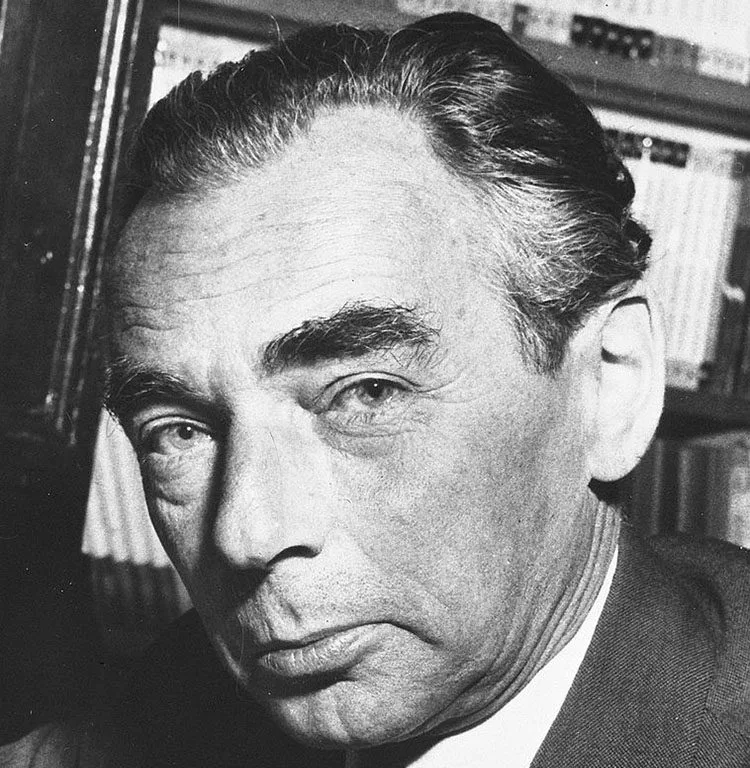

But this Hans Castorp, who also noted ‘a love of quarrels’ and ‘great irritability’ in Davos, wasn’t real; he was an imaginary character created by the great writer Thomas Mann (1875-1955), and the protagonist in Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain, who came into existence in 1920. The book was a global success; it was published in 1924, and in the first four years alone achieved a phenomenal print run of 100,000 copies. Then in 1929 Thomas Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. New editions and translations into 27 languages followed, and soon the whole world was reading about the microcosmic existence of the tuberculosis sufferers in Switzerland’s high-altitude sanatorium.

Even though The Magic Mountain has been hailed a stand-out work of the century, the novel actually ignores the reality. Tuberculosis was not the disease of the desolate rich; it was the disease of the poor, who couldn’t afford a sanatorium.

CONSUMPTION OR WHITE DEATH

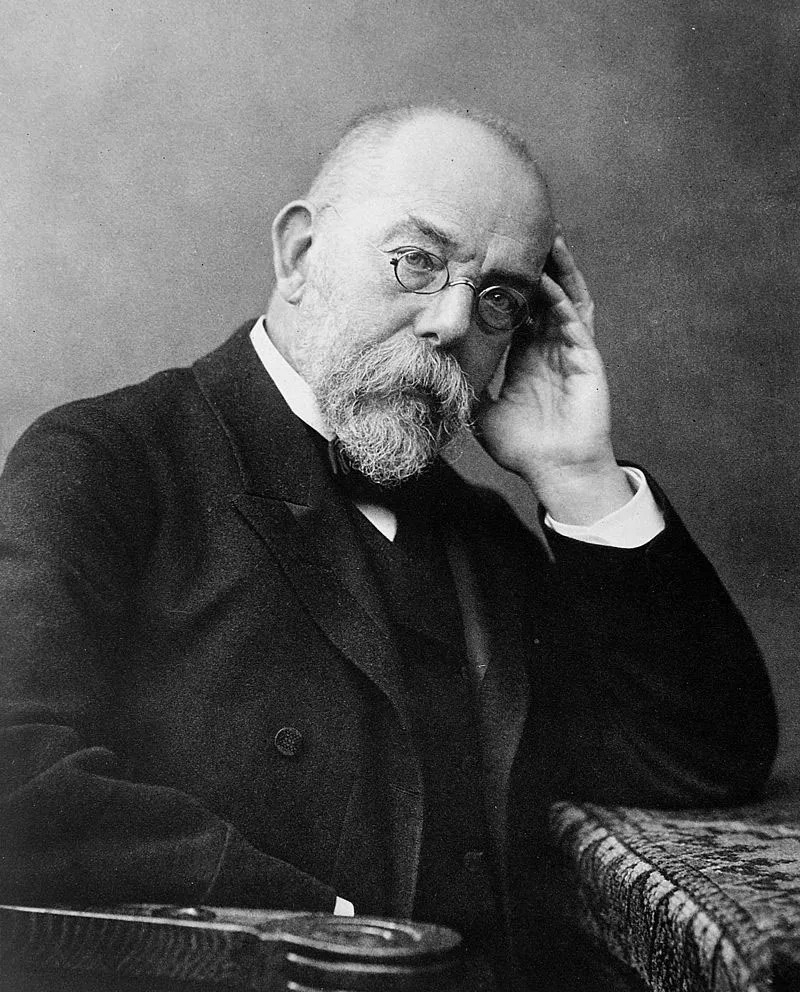

While today the COVID-19 virus is mostly killing older people and those with a pre-existing illness, 100 years ago tuberculosis struck down people in cramped housing who were forced to live in stuffy conditions with no fresh air. Tuberculosis was a social disease, and from the second half of the 19th century it carried off the people who dwelt in the tenements and dark backstreet courtyards. Even though the microbiologist Robert Koch identified the pathogen responsible in 1882 and developed the drug tuberculin, tuberculosis remained the number one endemic disease; it was also known as ‘consumption’, ‘white plague’ or ‘white death’. In the ten years from 1916 to 1925, more than 50,000 people died of pulmonary tuberculosis in Switzerland. The rule of thumb was that one in seven died from TB!

On 1 August 1921 the Nidwald writer Isabelle Kaiser, who suffered from the disease herself, published the poem Der moderne Drache [The modern dragon] in the Nidwaldner Volksblatt newspaper:

‘We think the world has made such strides forward,

For us, the age of dragons is past. (...)

And yet, my people, it races through every land

A monster with a polluted maw

It tears asunder the most innocent

Makes graceful, fine young bodies sick and sore

A ravening vulture, it wheels through the air

And pecks its way into each tender breast

As chafferer of death and the grave.

Wherever it swoops down, the air dies away. (...)’

The words are well chosen, and suggest the misery of the time: tuberculosis is personified as a ‘modern dragon’ and a ‘ravening vulture’. But as if that weren’t enough, in 1918 the disease of the century, tuberculosis, was joined by the Spanish Flu. Between July 1918 and June 1919, 24,449 people died of this new scourge in Switzerland alone – making Spanish Flu the country’s deadliest disaster of the 20th century.

DIRECT CONTACT OR DROPLETS

Just like tuberculosis, the Flu was transmitted through direct contact or droplets – in the age of coronavirus, we’re very familiar with that. After infection, the Spanish Flu took a dramatic course. In addition to the usual flu symptoms, sufferers developed spots on their faces, coughed up blood, their bodies became discoloured, and in the final stages they choked wretchedly. The violet-coloured bodies were piling up. The well-known writer Stefan Zweig noted in his Zurich diary in October 1918: ‘A world-wide epidemic, against which the plague in Florence or similar episodes in history are a children’s game. Every day it gobbles up 20,000 to 40,000 people.’

After two waves of the flu, the curve flattened again. But that of the TB sufferers did not. Doctors gave talks up and down the country, and in the cities restaurants screened ‘instructional films for public enlightenment’ which, as the Luzerner Neusten Nachrichten newspaper wrote in 1921, served to ‘defend against this terrible scourge of humanity’. Rather than today’s social distancing, a warning circulated: ‘Everyone who spits on the floor is spitting in the lungs of the next person!’ Cantons and private aid organisations such as lung leagues set up specialist high-altitude clinics throughout Switzerland. At the end of the 1920s, there were no fewer than 88 sanatoria in Switzerland – like the one Thomas Mann described in The Magic Mountain.

Davos, by the way, had to vindicate itself, because Thomas Mann had ‘brought the place into disrepute as far as health is concerned’. The town’s tourist office commissioned the author Erich Kästner, with his humorous style, to write a light-hearted novel set in Davos. Kästner wrote a book with Alfons Mintzlaff as the main character. In reference to Mann’s The Magic Mountain and to Goethe’s Faust he gave his main character the allusion-laden moniker Der Zauberlehrling [The sorcerer’s apprentice]. But the book was not a success, because unpleasant stories usually go down better than nice ones. That too we know from the present.