The reformer and the ghosts

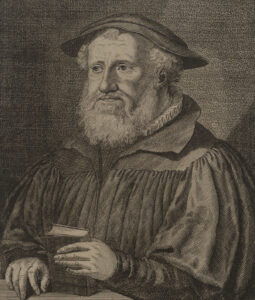

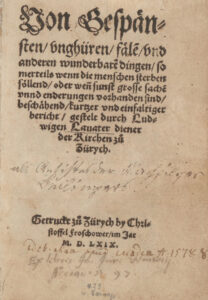

Ludwig Lavater was not only the successor to Huldrych Zwingli, but also a great lover of ghost stories, which he collected and published in a book.

When the theologian collected ghost stories

An armed legion in the sky