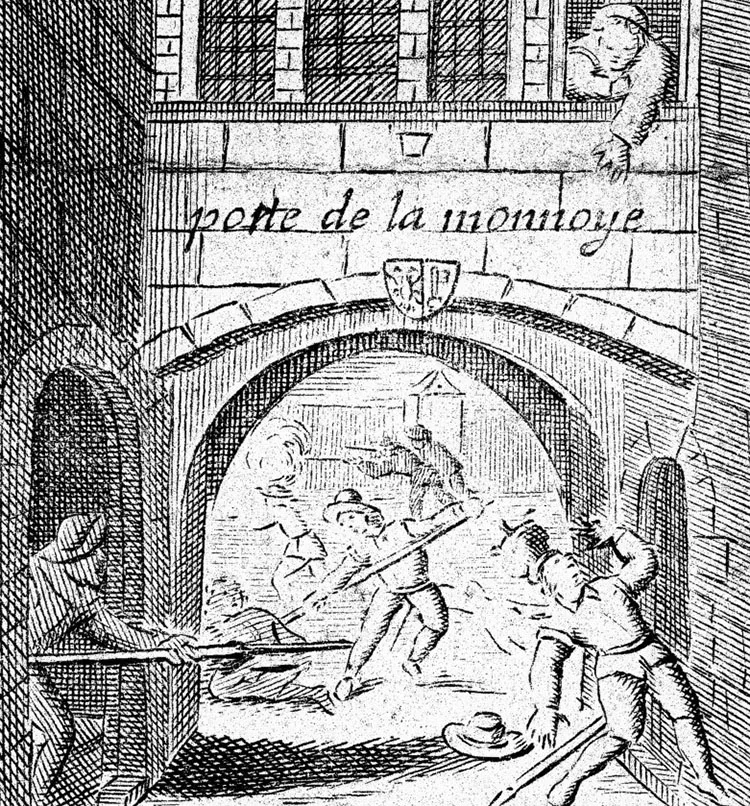

The Geneva Escalade

In December 1602, the Duke of Savoy attempted to take the city state of Geneva with a surprise attack. The attack was thwarted, and the city finally became independent.

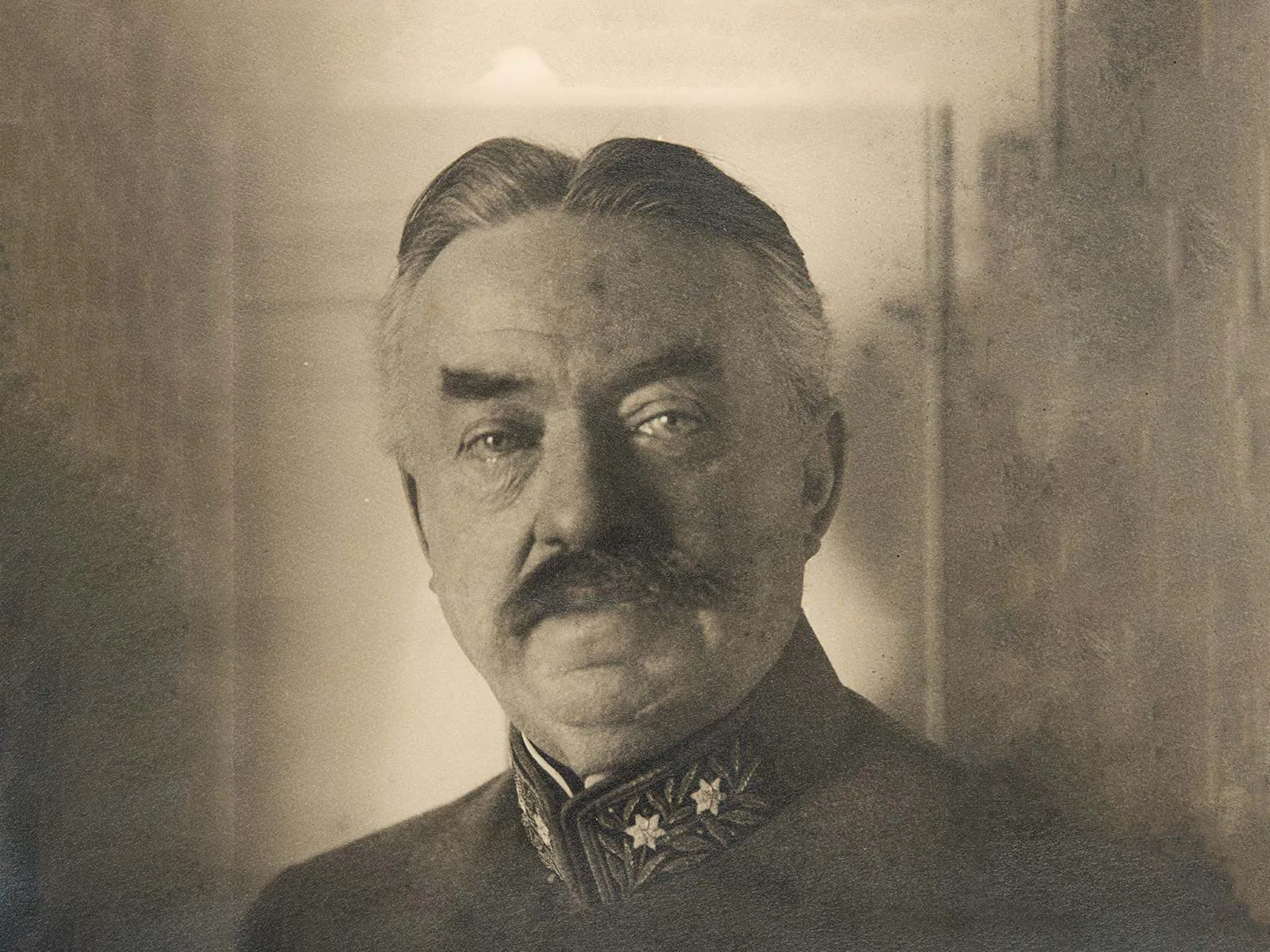

The defeat spelled a definitive end to the Savoyards’ dream of great power in the region, and was a humiliation for Charles Emmanuel. But the military embarrassment of that December night wasn’t the only bitter pill he had to swallow. In 1603, the Duke also had to recognise Geneva’s independence, in the Treaty of Saint Julien. This meant that his scheme to establish the city as his capital in the Alpine foothills was off the table, along with a plan to stamp out Protestantism in the region. To make sure the Savoyards adhered to the peace agreement, they were ordered not to concentrate troops or build fortresses within four miles of Geneva. In addition, the city on the Rhone was exempted from any liability to pay taxes to Savoy.

Legend of the soup cauldron

The Genevan victory delighted the city’s inhabitants, and was a considerable setback for Savoy. It was also good news for the Swiss Confederation. However, feelings differed on the question of what should happen next with the city on the Rhone. While the Reformed cities of Bern and Zurich supported the Genevans, and had even agreed to this in writing with a long-term protective alliance in place since 1584, the Catholic cities did not want Geneva to be fully incorporated into the Confederation. The denominational conflict continued to smoulder among the 13 cities, and any shift in the fragile balance was risky. So Geneva remained an allied canton and, after a brief French interlude between 1798 and 1814, became an autonomous canton only at the beginning of the 19th century.