Albert Gallatin: A Swiss Founding Father

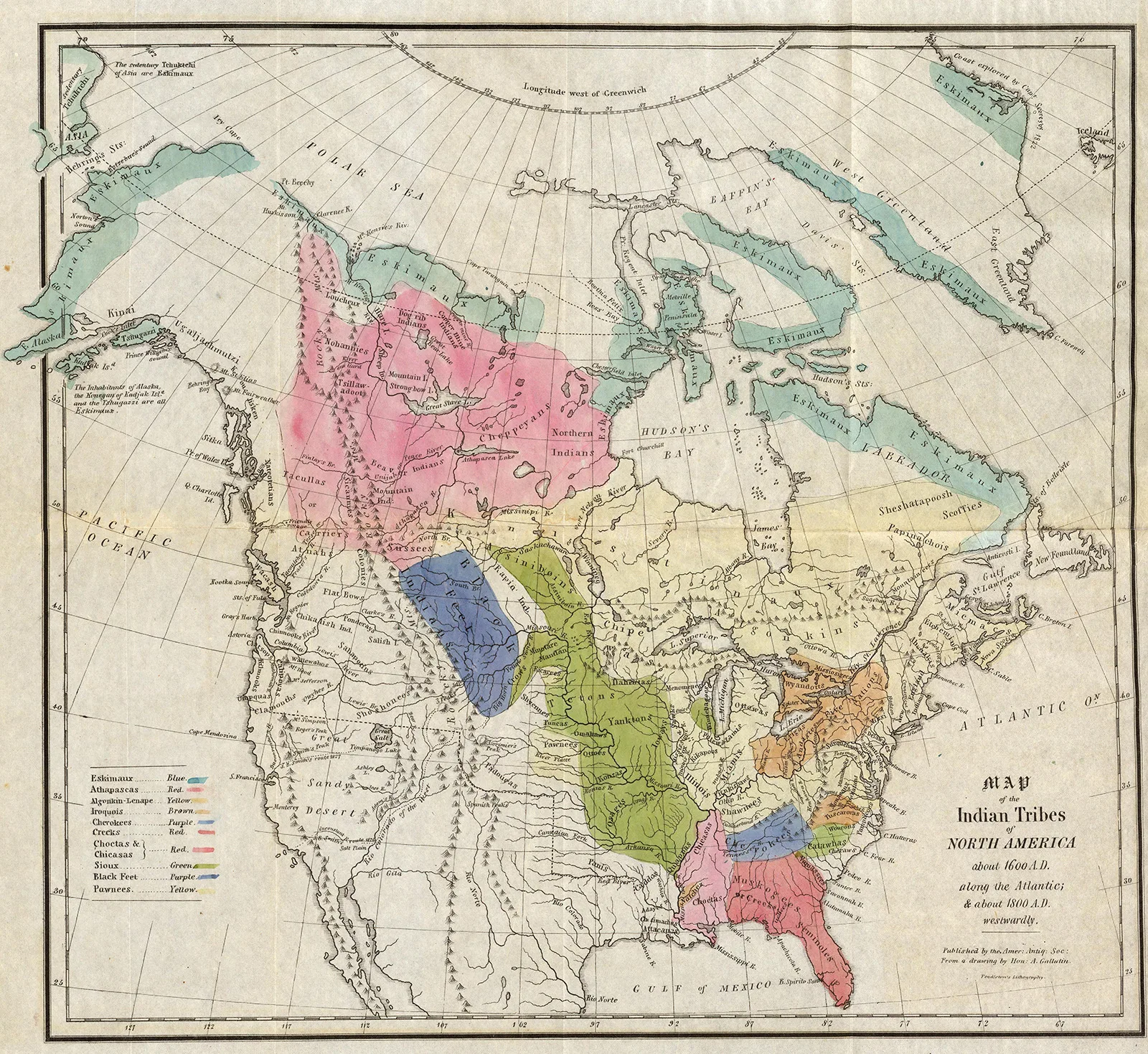

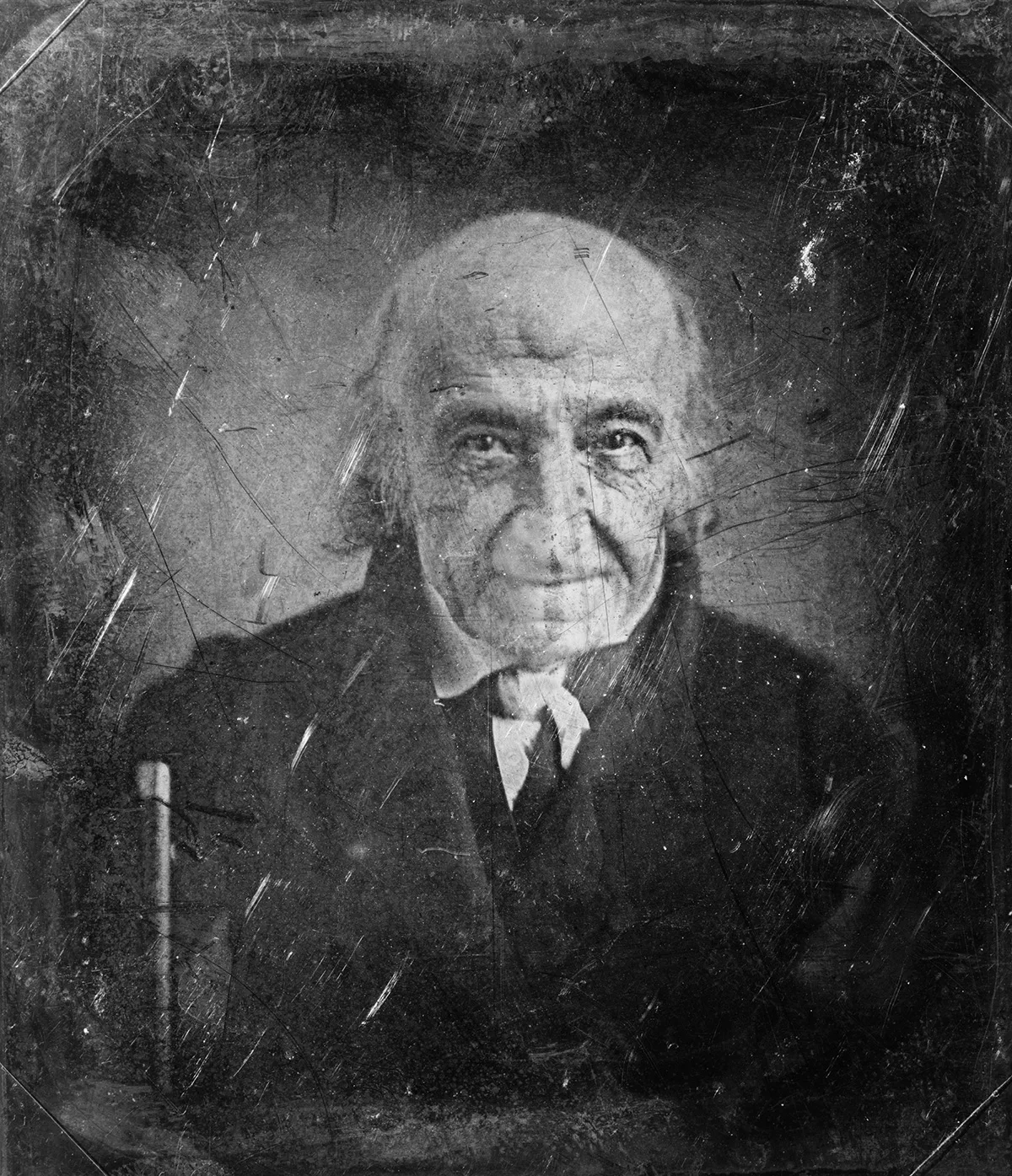

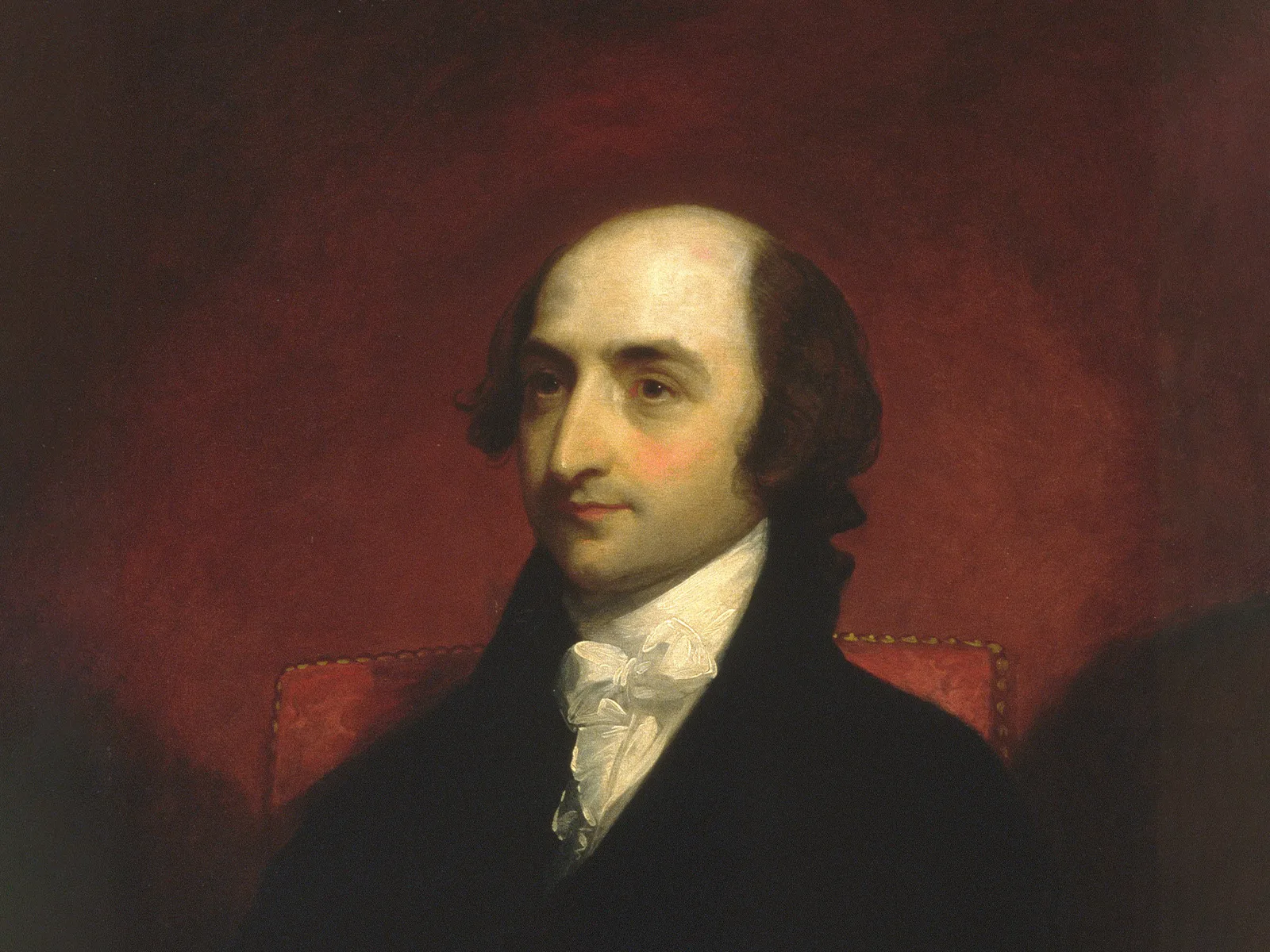

Albert Gallatin (1761-1849) is often referred to as “America’s Swiss Founding Father” by historians due to his significant contributions to American government, finance, diplomacy, and cultural life.

Early Life in Geneva and the United States

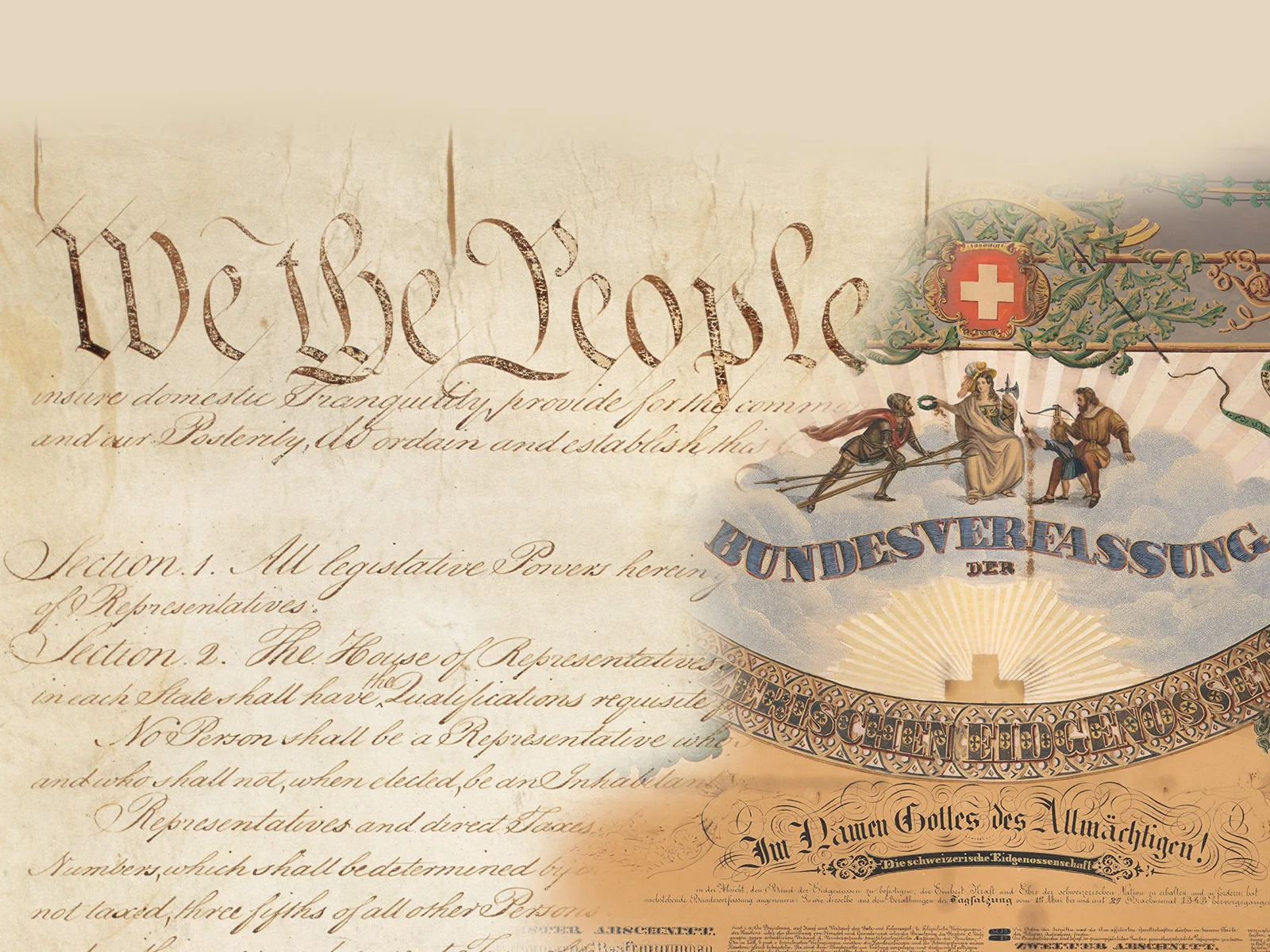

The whole of the Bill [of Rights] is a declaration of the right of the people at large or considered as individuals… It establishes some rights of the individual as unalienable and which consequently, no majority has a right to deprive them of.

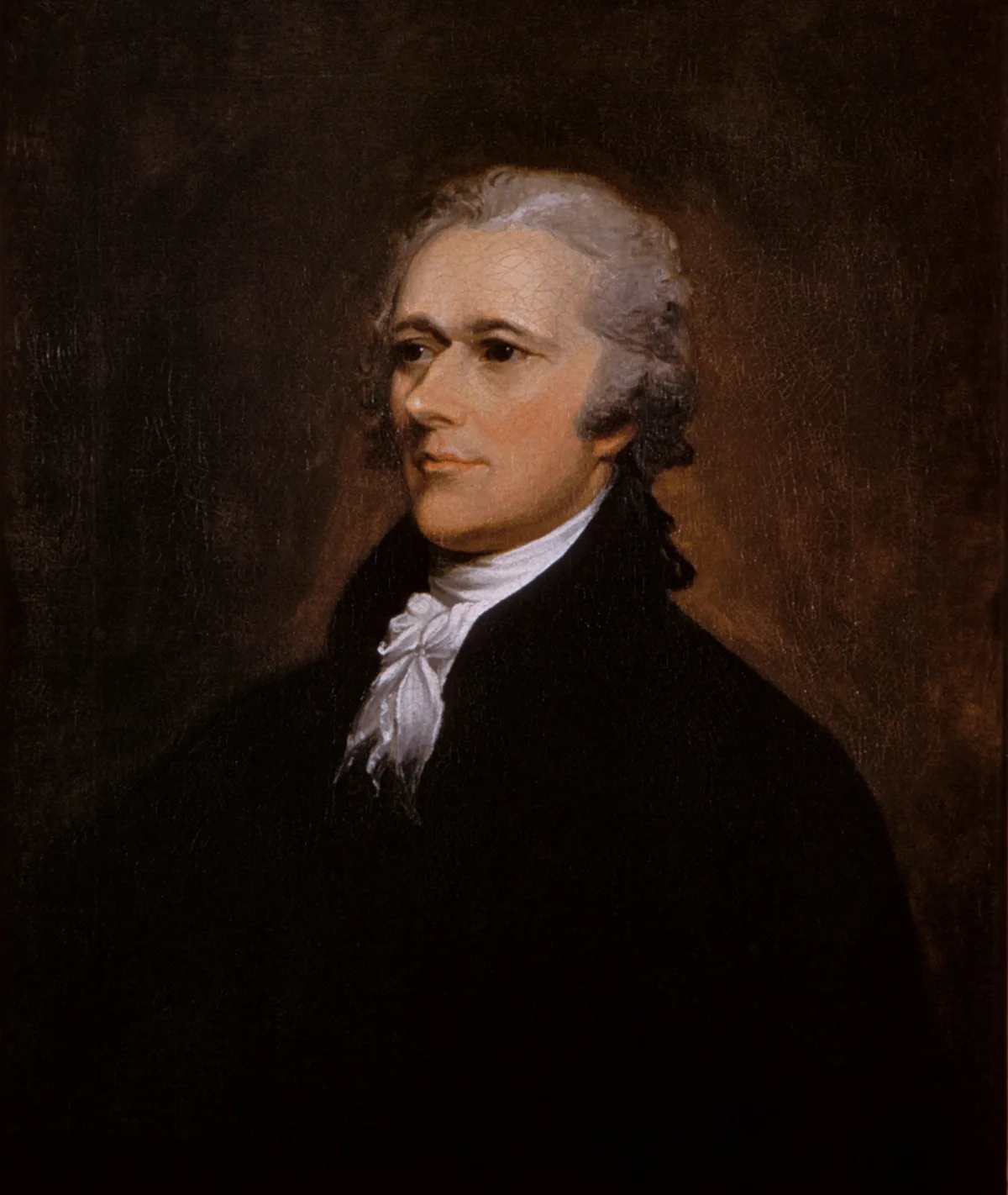

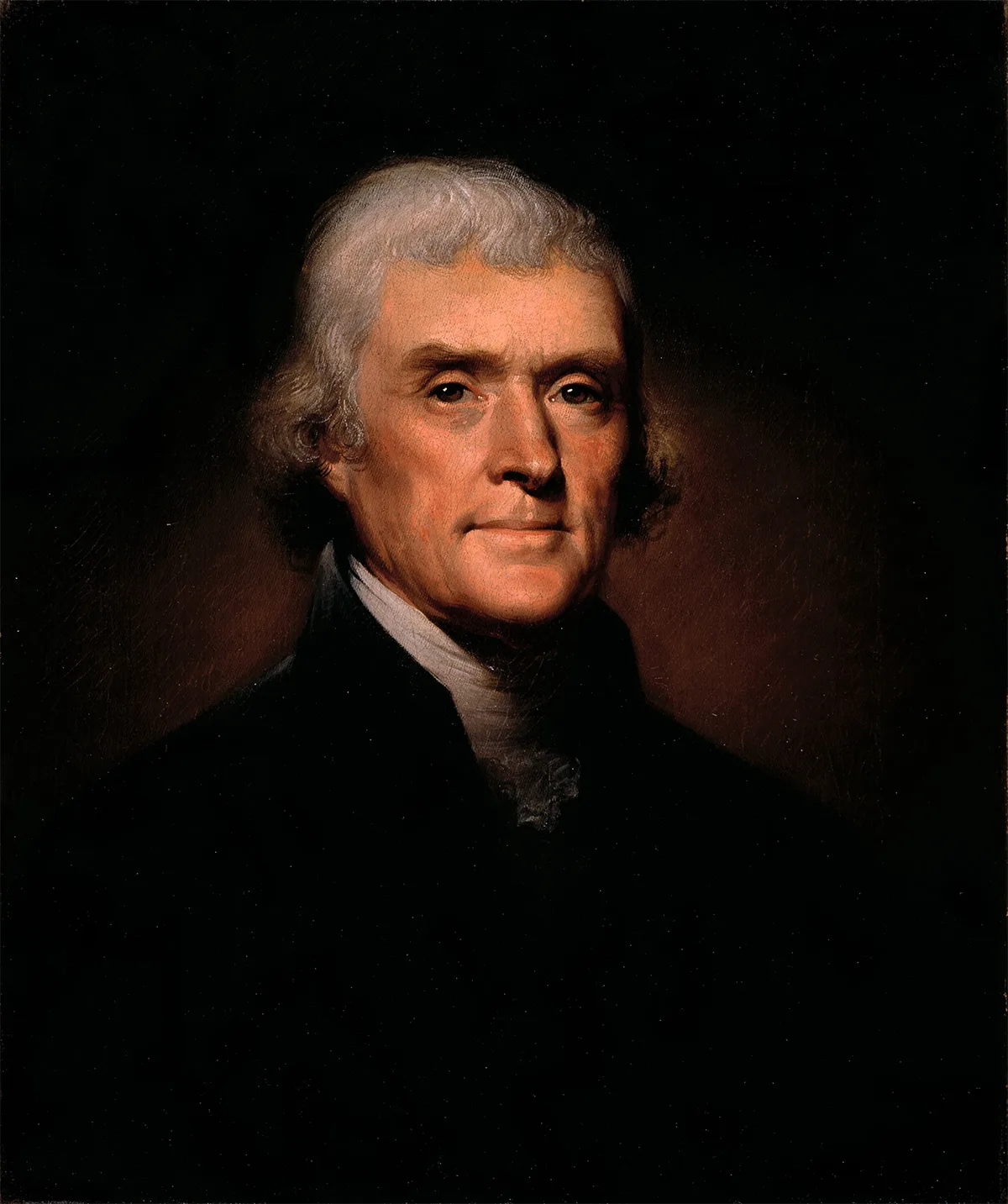

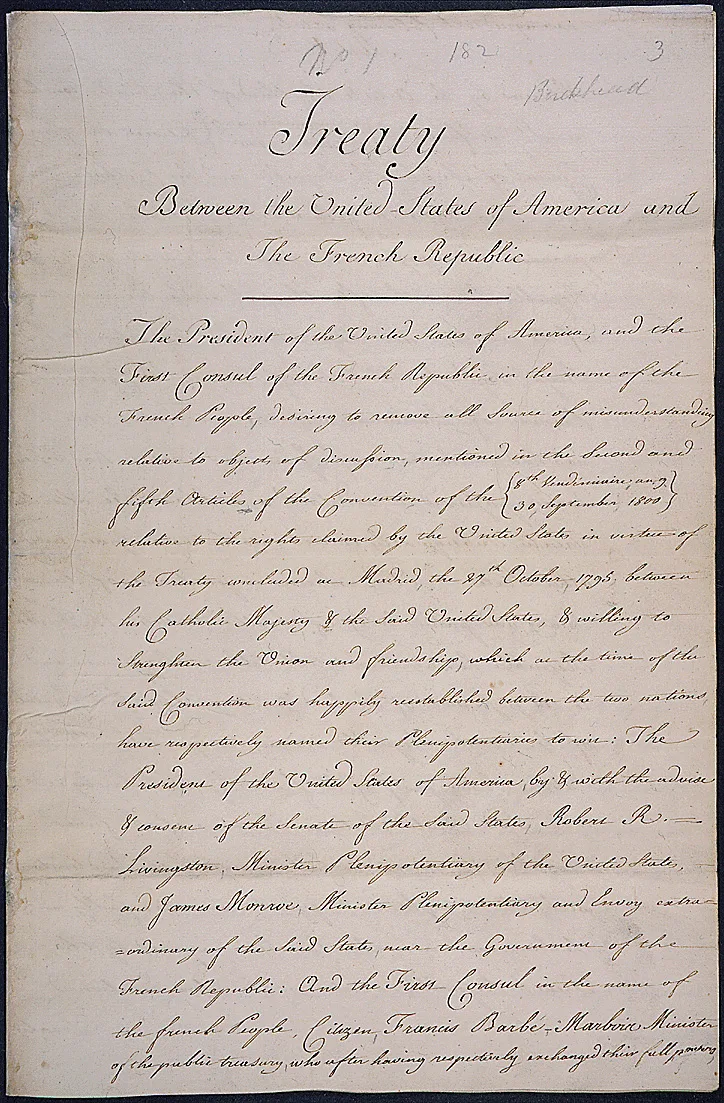

Financier and Diplomat par excellence

The democratic process on which this nation was founded should not be restricted to the political process, but should be applied to the industrial operation as well.

Humanitarian Pursuits & Legacy