Homesick for the mountains

200 years ago, homesickness was thought to be a typically Swiss affliction. It was triggered by ‘Kuhreihen’, old herdsmen’s songs. The children’s book character Heidi also suffered from homesickness.

In 1688, Alsace doctor Johannes Hofer described a new, insidious disease. The symptoms: high fever, irregular heartbeat, debility, stomach ache and melancholy. In some cases, the disease could even be fatal. And one particularly striking feature was that it only affected Swiss people, particularly Swiss mercenaries who were far from home fighting battles on behalf of foreign powers. Hofer dubbed the condition ‘nostalgia’ or ‘homesickness’. He believed the cause was psychological, and that it lay in ‘excessive thinking about one’s homeland’, triggered by the sufferer’s spending time in unfamiliar surroundings.

Not long after Hofer’s discovery, Zurich doctor and naturalist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733) thought he had found a much less emotional trigger for the condition. In mountain-dwellers accustomed to living at altitude, he believed, the lower air pressure when they spent time in lower-lying areas resulted in a thickening of the blood. People from the mountains of Switzerland would therefore be particularly vulnerable to the disease. If they descended from their Alpine meadows into the lowlands, or as far afield as foreign countries situated at sea level, they would be stricken by homesickness.

The ‘Kuhreihen’ – Switzerland’s yearning song of home

In the 21st century, homesickness is no longer seen as a disease, but as a feeling associated with the same set of emotional responses as lovesickness or wanderlust. There would no longer be any notion of homesickness as having once been a typically Swiss disease if Basel physician Theodor Zwinger (1658-1724) had not suggested, in a paper published in 1710, that a specific melody triggered the disease in Swiss mercenaries and drove them to the point of desertion. The fateful melodies were traditional old herdsmen’s songs known as ‘Kuhreihen’.

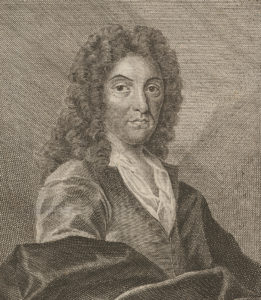

The Swiss mercenaries, often from poor peasant families, sang the songs when far from home to bolster their flagging spirits. It seems plausible that these feelings caused homesickness in some of these young men, and perhaps even prompted them to desert. It was even said that, for fear of their Swiss soldiers deserting in droves, the French banned the singing of Kuhreihen on pain of the death penalty. Whether this was actually so is disputed. But the most famous philosopher of the Enlightenment, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), wrote about it in his work A Complete Dictionary of Music. The mercenaries ‘who sang it dissolved in tears, deserted, or were left heartbroken, so powerfully did the song arouse in them the ardent desire to see their homeland once more’.

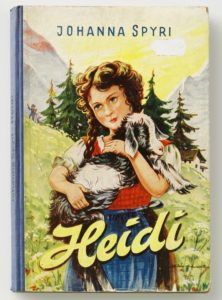

Even Heidi suffered from homesickness

It was also Rousseau who, in 1762, laid the ideational foundation for Johanna Spyri’s (1827-1901) Heidi, in his magnum opus Emile, or On Education. Rousseau was sceptical of big-city and courtly society, and the ‘progress’ of civilisation. The education of his protagonist Emile took place far from civilisation. Nature was the preferred teacher. In Spyri’s novel, written about 100 years later, the orphan girl Heidi represents the unspoiled child of nature, while in the city unhappiness, strict rules and formality prevail.

Heidi is one of the most successful children’s stories in Switzerland, and in world literature. It is a timeless novel that has been translated into more than 50 languages and adapted in numerous forms for the stage, film and television. In essence, Heidi is the prototypical story of homesickness. The child of the Alps, happy and healthy in her grandfather’s care, falls ill when she is sent to live in the city, far from the natural environment of her upbringing. In the city, she displays the typical symptoms of the ‘homesickness’ disease: yearning, sadness, hallucinations and sleepwalking. The only cure is an immediate return to her home. In the medical discourse, women and children were for a long time not considered susceptible to the homesickness disease. Johanna Spyri’s novel painted such an acute picture of homesickness in Heidi that nowadays, it is children who are thought to be most prone to homesickness.