In the hairdressing salon of the Turkish princess

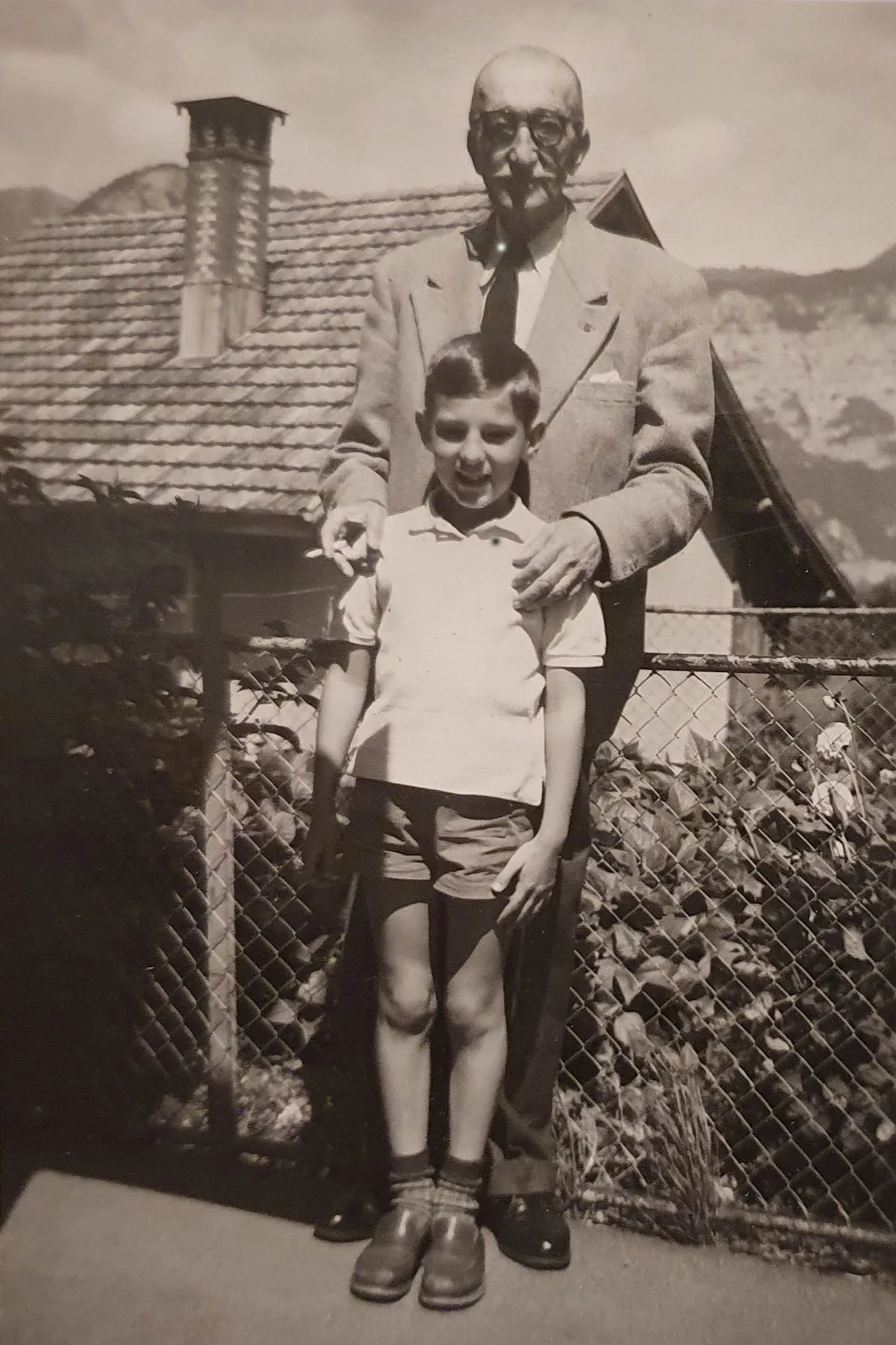

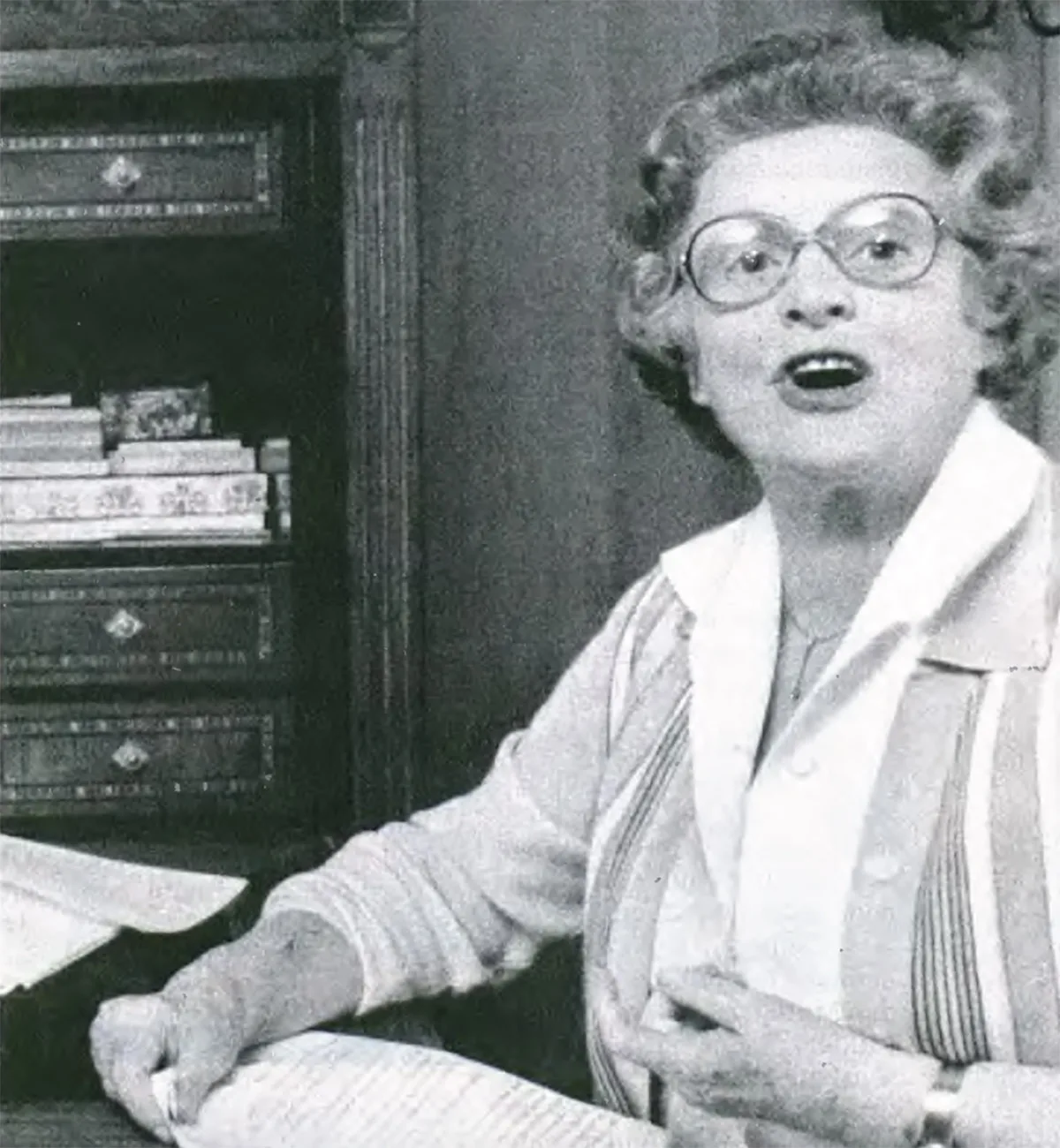

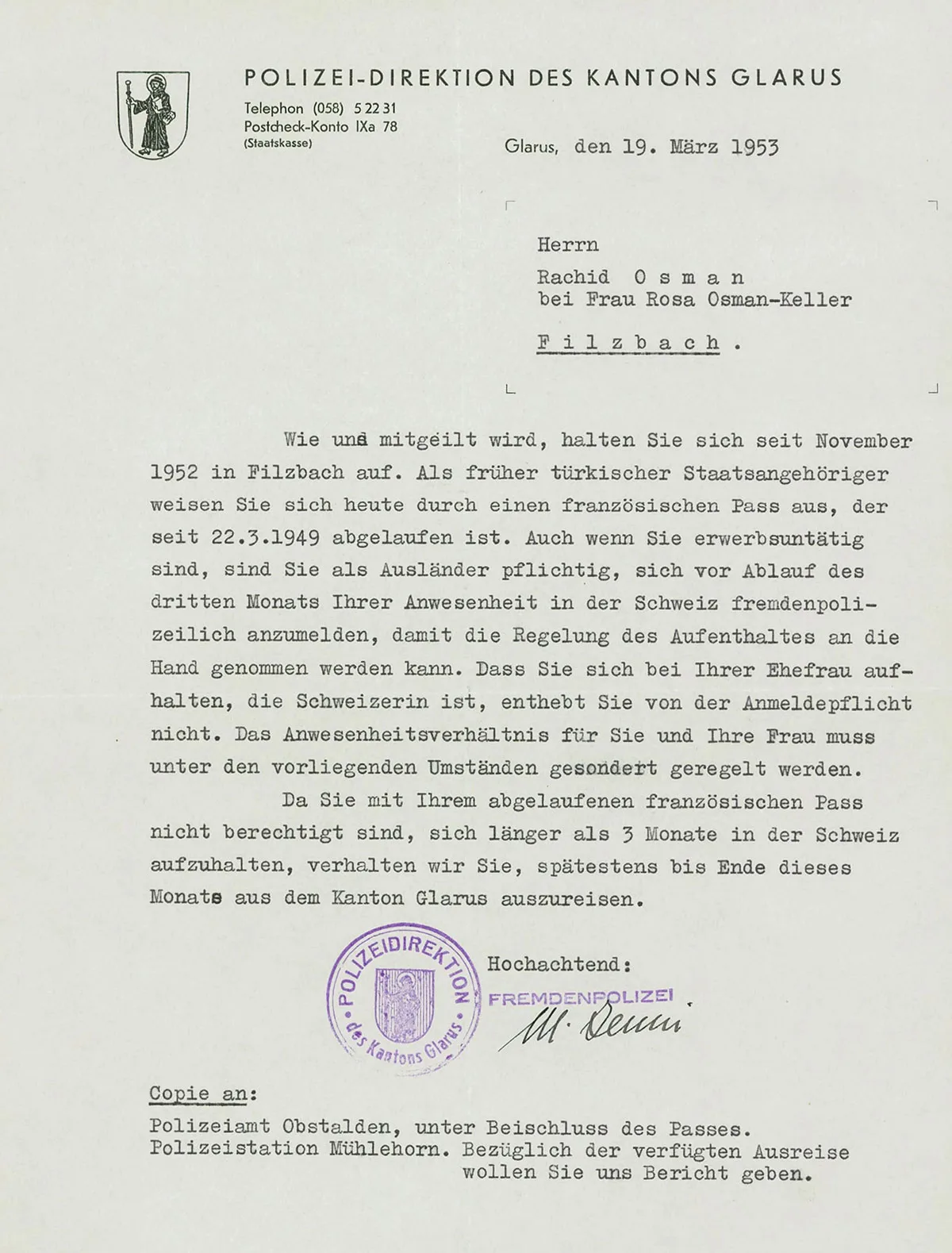

The last representative of the Ottoman Empire was Rachid Osman. He spent his twilight years in a small village in Glarus. His wife Rosa Osman-Keller earned a living as a village hairdresser to support herself and her once fabulously wealthy husband.

On an equal footing with Europe’s powerful figures

A life straight out of a movie