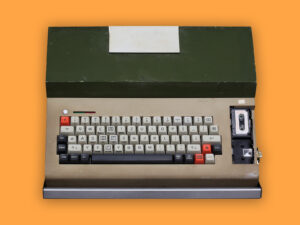

Scrib: The laptop made in Switzerland

Germany, UK, USA – whichever way you look at it, the computer is a foreign import here. But one of its forebears was a genuine Swiss creation: the portable writing system called Scrib, specially developed for journalism.