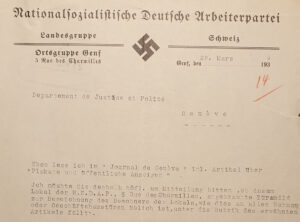

The Geneva NSDAP

At the beginning of the 1930s, Geneva was deeply divided between right and left. These were ideal conditions for the formation of a local branch of the NSDAP.

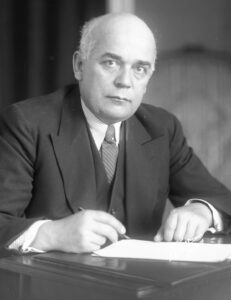

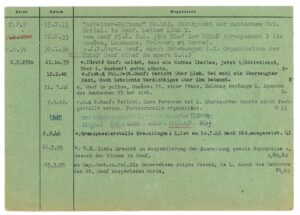

Geneva NSDAP keeps the pressure on

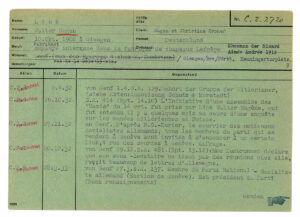

Eugen Link’s activities were meticulously monitored. Swiss Federal Archives