A Swiss success story: the tale of an espionage recorder

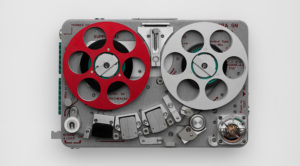

The size of a wallet, accurate and reliable: the Nagra SN, a tape recorder made by the Swiss firm Kudelski, was destined from the beginning to go down in history. This marvel of analogue audio technology was developed in the early 1960s at the request of John F. Kennedy.

American President John F. Kennedy contacted the well-known Swiss company Kudelski in search of a small recorder for covert audio recording by the CIA, the US intelligence service. The Nagra SN (Série Noire) was supplied exclusively to the CIA until the early 1970s.

Kudelski AG had made a name for itself in the 1950s with its Nagra recorders. These machines offered exceptional sound recording and playback. What was so special about the Nagra was that the machines were portable and robust. As a result, they quickly found their way into radio, television and the film industry – fields in which sound was recorded ‘on location’. The company’s founder was engineer Stefan Kudelski, born in Warsaw in 1929. In 1939, his family fled to Switzerland via Hungary and France. While a student at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, he made his first tape recorder. In 1951 he set up his company, and started with the production of a portable tape recording device for radio reporters, the Nagra I. He delivered the first devices to radio studios in Lausanne and Geneva. With its professional recording devices, the firm quickly became the industry leader. And in the decades that followed, Stefan Kudelski won four Oscars in the Scientific and Technical category.

The name Nagra is derived from the Polish word nagrywać/nagrać and means ‘to record/recorded’. It should not be confused with the abbreviation ‘NAGRA’, which stands for the National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste set up in 1972.

THE SECRET FILES SCANDAL OF 1989

In the 1970s, the Nagra SN devices were also used by the secret police and, as a specimen in the Police Museum in Zurich attests today, by the Swiss police. It owes its success to the Cold War. In view of the nuclear threat, safeguarding the country and its population was becoming more important in Switzerland. Counterintelligence and surveillance were among the priorities of Switzerland’s federal police force, and in particular the Political Police – the division that acted as the investigative and intelligence service of the Federal Prosecutor’s office. Hidden microphones, bugging devices, miniature radio units and camouflaged cameras were used.

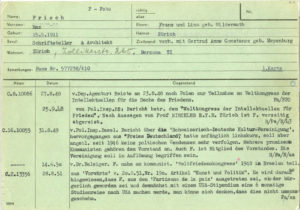

According to a 1958 Federal Council resolution, the Political Police division was tasked with the ‘monitoring and prevention of activities that could put at risk the internal or external security of the Confederation’. What this meant became clear in 1989 with the ‘secret files scandal’, when the parliamentary commission of inquiry (PUK) investigating the case of Federal Councillor Elisabeth Kopp exposed the extent of the monitoring. In its report, the PUK claimed that the registry of the Federal Police contained around 900,000 index cards (files). The entries were based partly on observations by official organs, but also contained information provided by anonymous private individuals. The files, the PUK found, were rife with false reports and trivial information. In addition, people from the left of the political spectrum seemed to have been systematically monitored. This caused general outrage among the population. More than 300,000 people demanded access to their files.

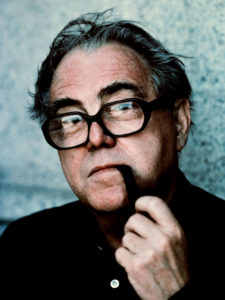

Those affected included the novelist and intellectual Max Frisch, who was kept under surveillance for more than 40 years, from 1948 to 1990. His criticism of arrogant institutions and his trips to Eastern Europe, among other things to a peace congress, had obviously aroused suspicion. On 1 August 1990, he received his file: 13 index cards, with much of the information blacked out. Angry and frustrated over the dilettantism of the government officials, he sat down at his typewriter. He annotated and corrected each entry. The corrections to the first index card alone took up five pages. The typescript of this final opus by Max Frisch was published by Suhrkamp posthumously in 2015 with the title «Ignoranz als Staatsschutz?» (Ignorance as State Security?).

It remains unknown whether a Nagra SN was ever used in the surveillance of Max Frisch. What we do know is that the Nagra espionage recorder’s success story ended in 1989, not just because of the secret files scandal, but above all due to the fall of the Berlin Wall, as a result of which the Swiss state security organs lost the main object of their interest – the scenario of a Communist overthrow by the left.

See the Nagra SN

The little miracle device that looks like a James Bond gadget can be viewed in the permanent exhibition ‘History of Switzerland’ at the National Museum Zurich. Together with a tap-proof telephone camouflaged as a suitcase from the Police Museum in Zurich and a media station that also contains portions of Max Frisch’s comments on his file, the exhibition sheds light on the subject of state security in Switzerland during the Cold War.