Reformation in the countryside

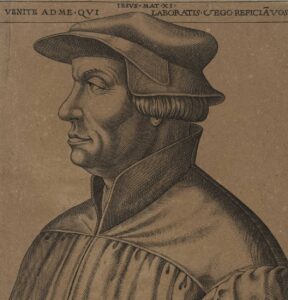

While Zwingli was preaching the Reformed faith in Zurich in the 16th century, the altered circumstances of life led to frictions in the countryside on a greater and lesser scale.

Priests in love and fickle congregations

Struggle and every soul