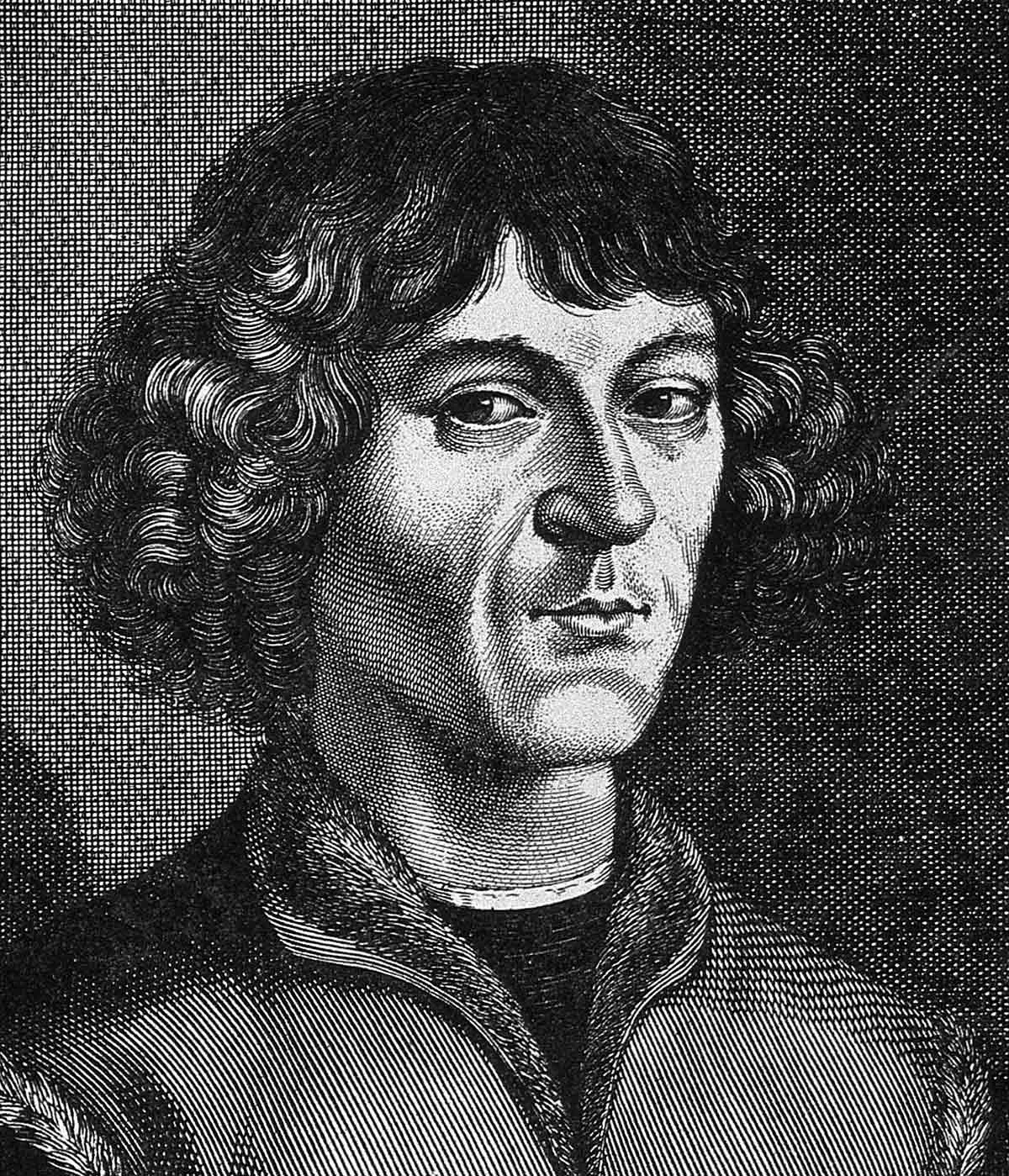

Copernicus the heretic

Nicolaus Copernicus is considered one of the founders of modern astronomy. His heliocentric planetary model unleashed an outcry in Reformation circles, especially in Switzerland.

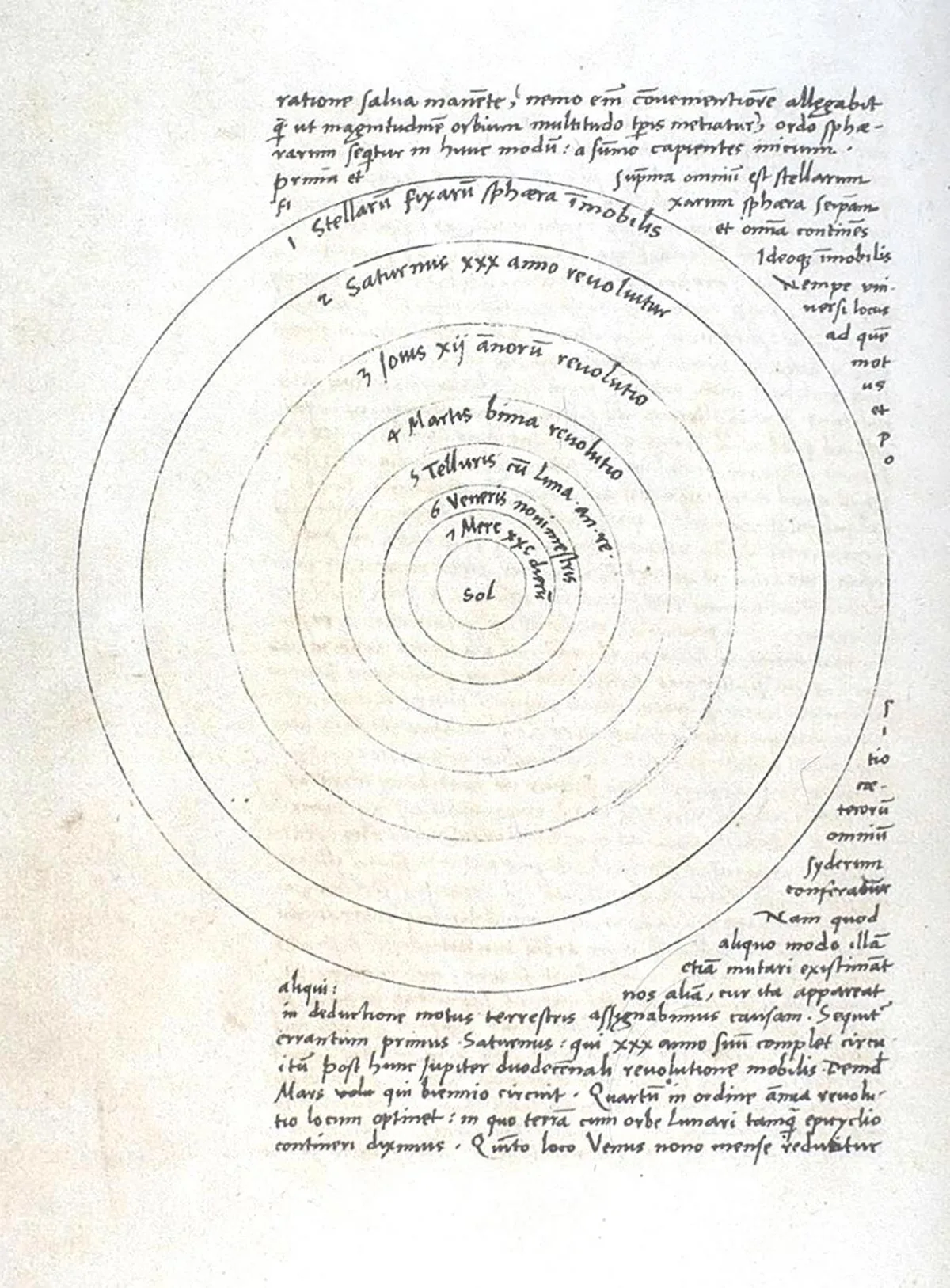

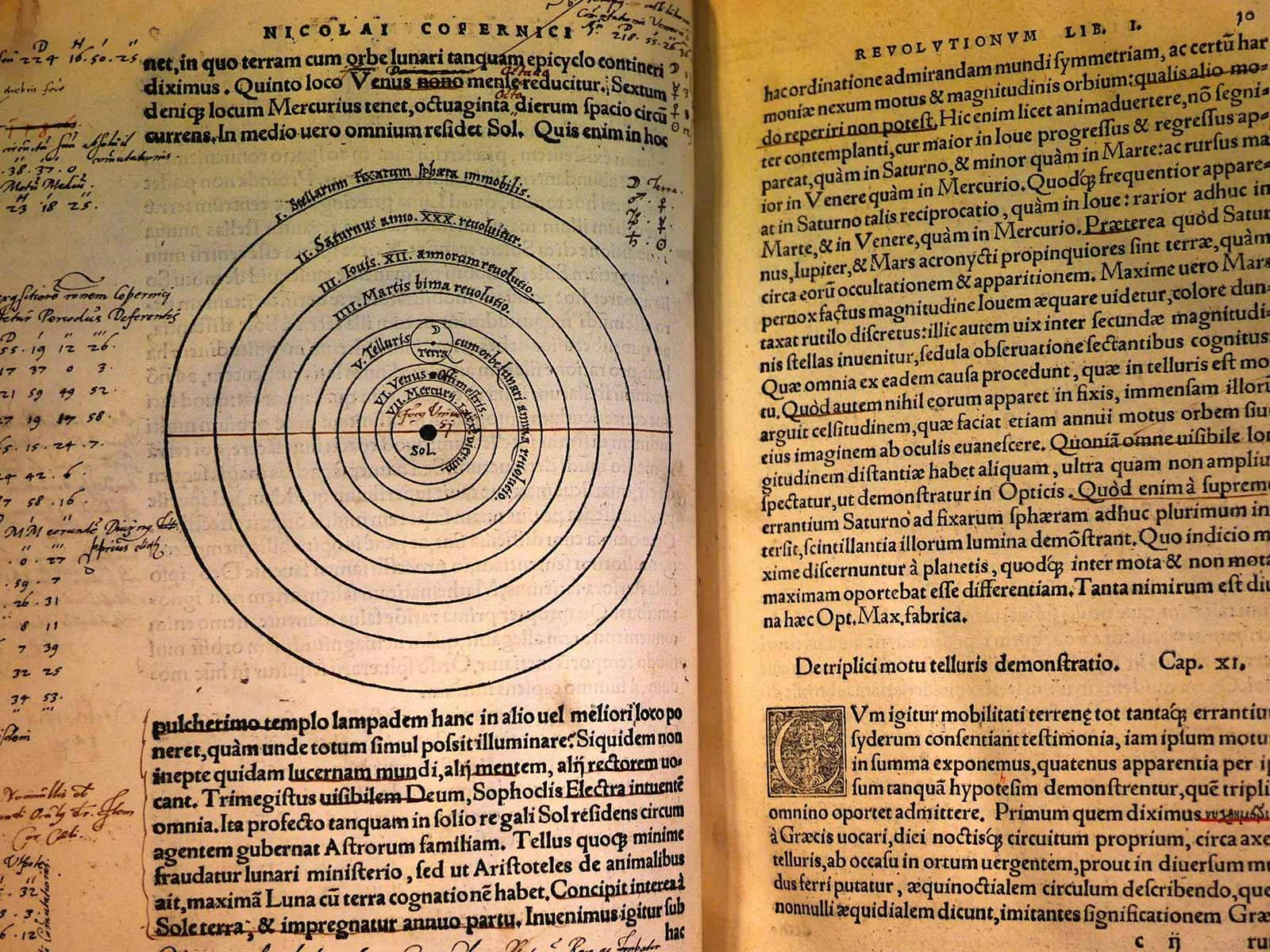

Animation of the Copernican planetary model from De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. More information about the animation can be found at: thomasweibel.ch