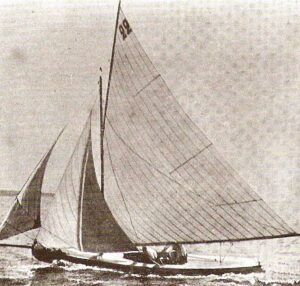

The first female Olympic champion

New York-born Hélène de Pourtalès (1868-1945) of Geneva won gold at the 1900 Olympic Games. Largely unknown today, this pioneering yachtswoman paved the way for other women to compete at the Olympics.

Future husband had to be a yachtsman