Sisi the poetess and her long journey onto the bookshelf

Elisabeth of Austria-Hungary was an empress, and a poetess as well. Why her personal notes are in Switzerland’s Federal Archives, and why they remained unpublished until 1984...

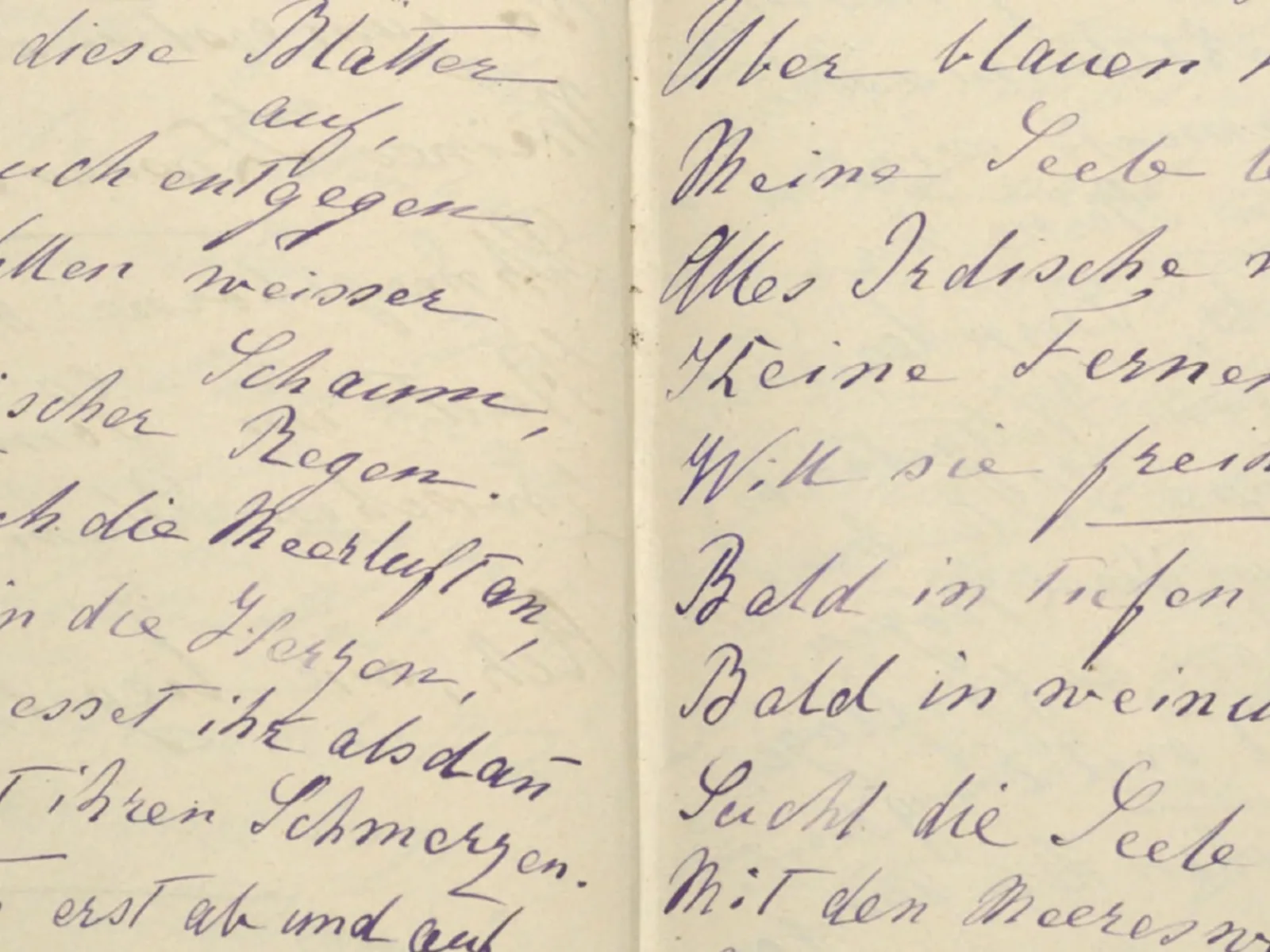

And on the North Sea’s surging waves

My beloved, you lay prone

Soaked with a thousand filaments

I have you, coated with salt and foam

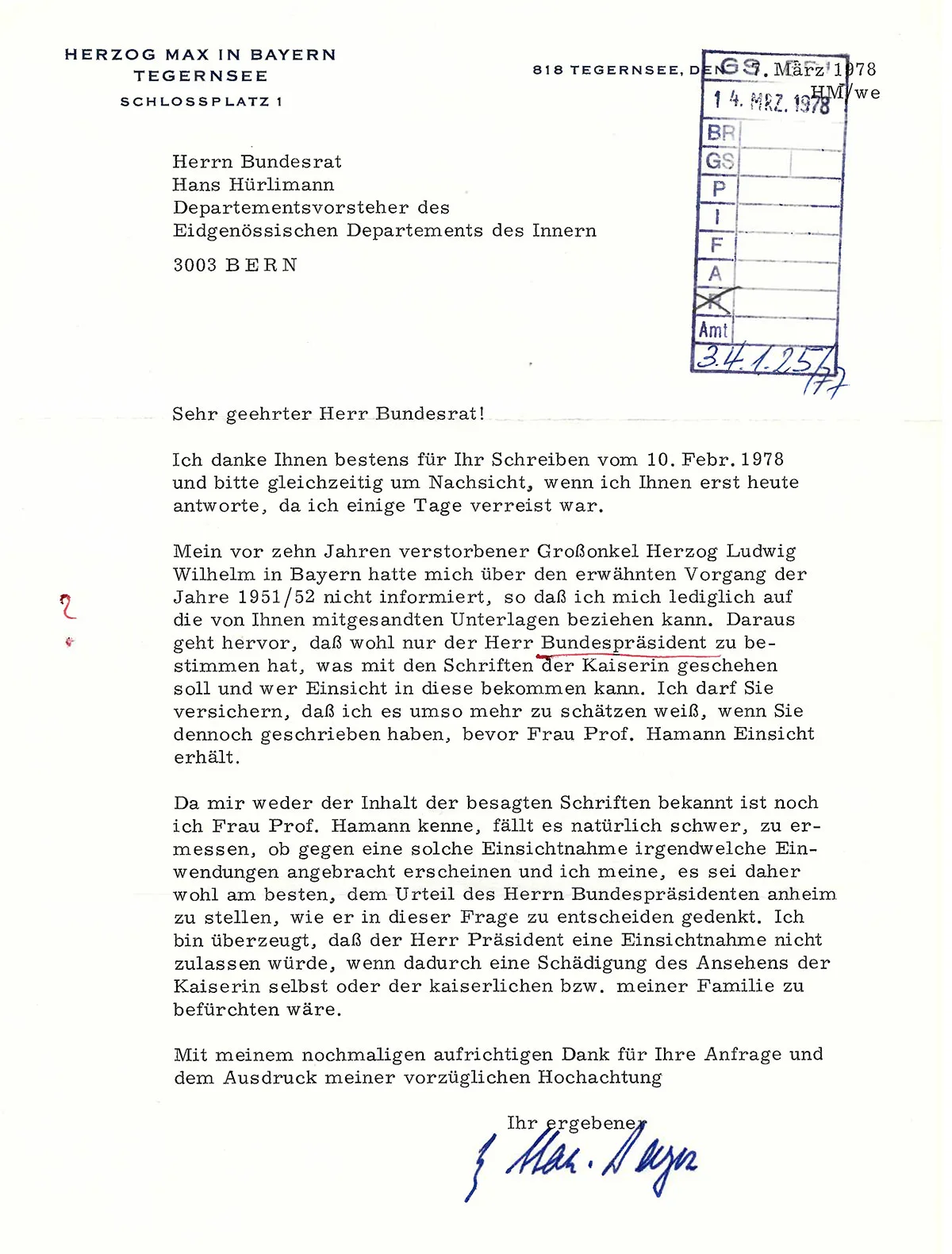

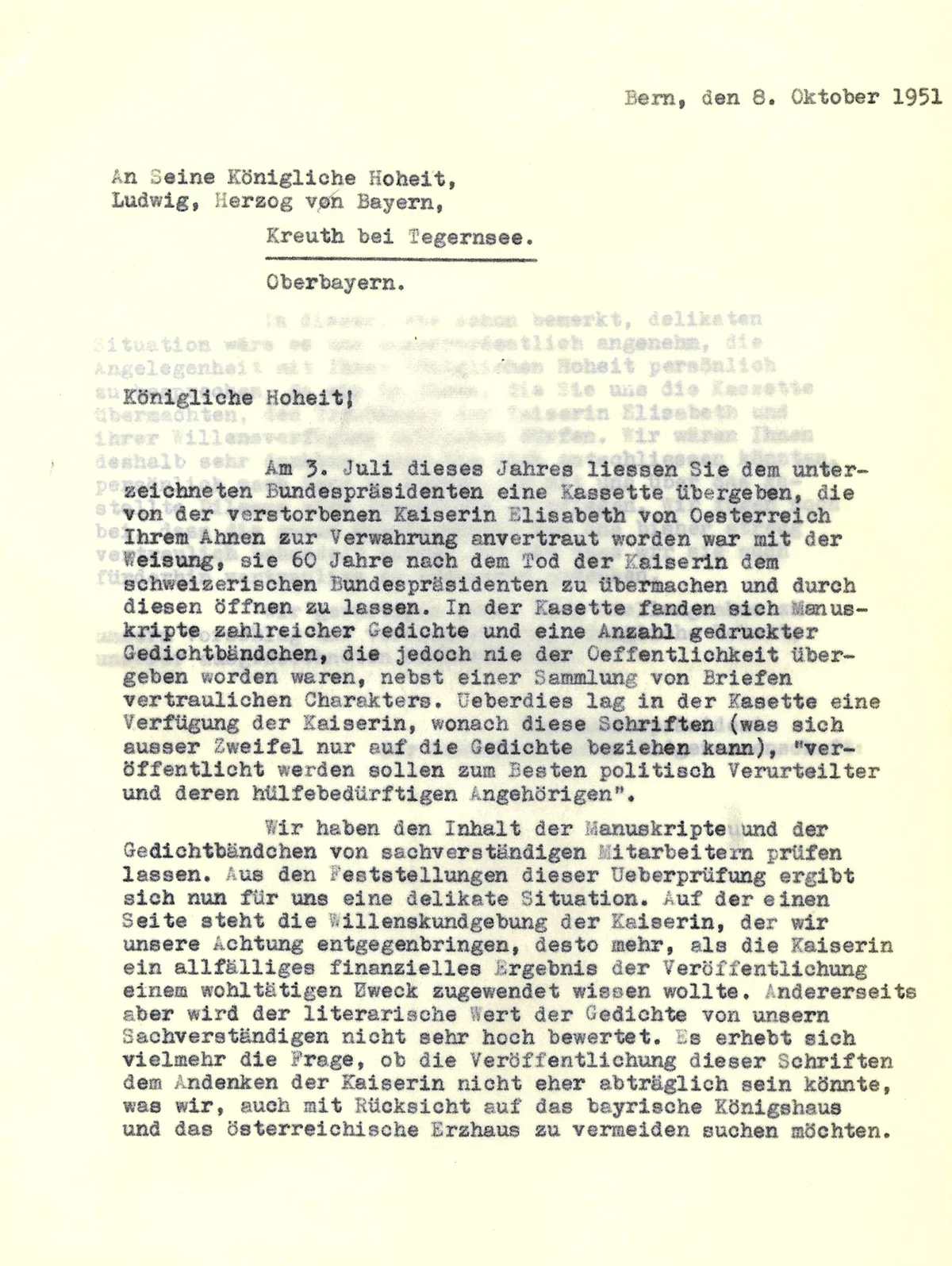

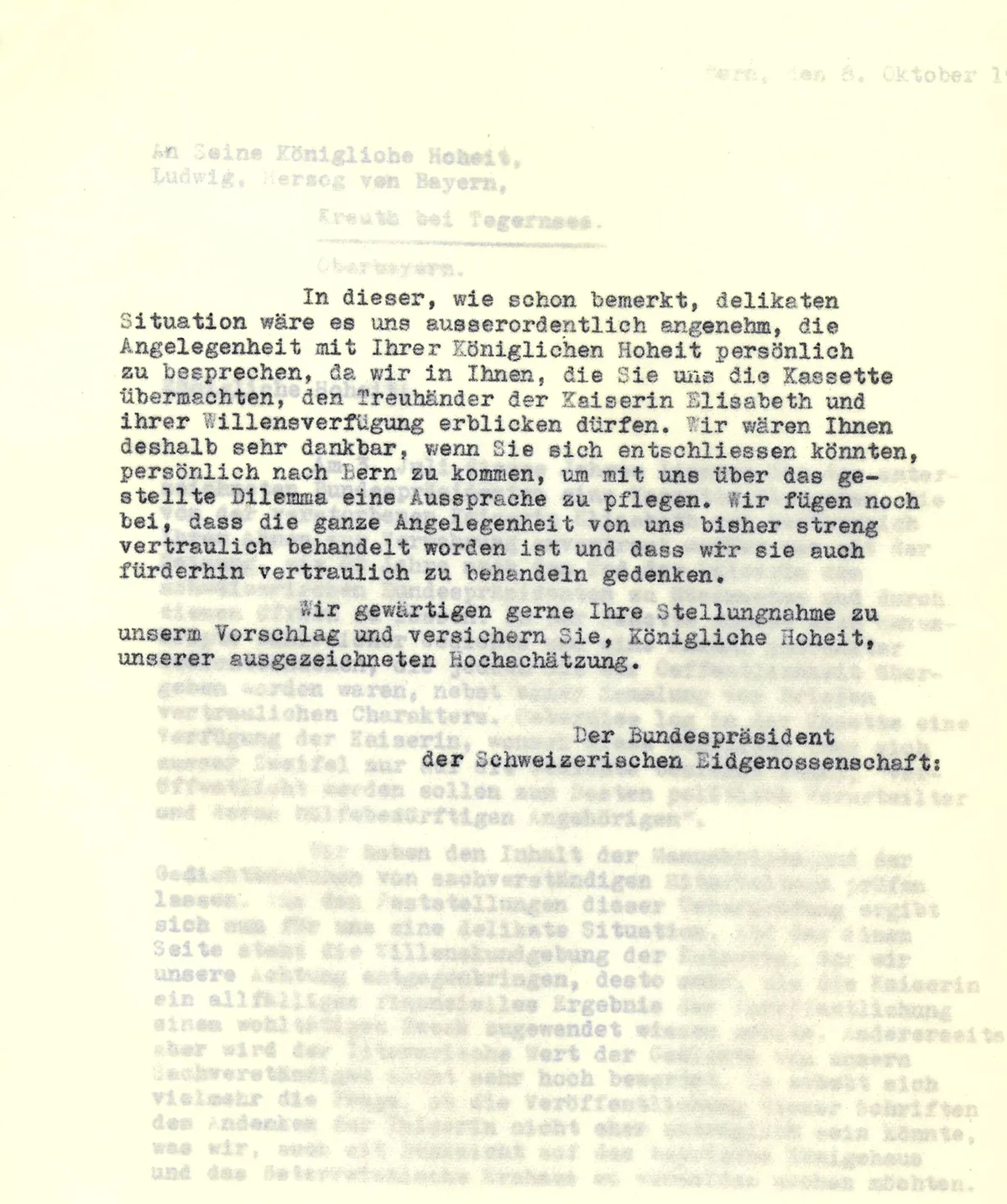

Letter to Ludwig, Duke of Bavaria, dated 6 October 1951. Swiss Federal Archives