Karl Bodmer and the Native Americans

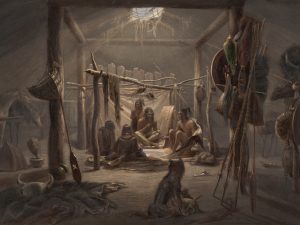

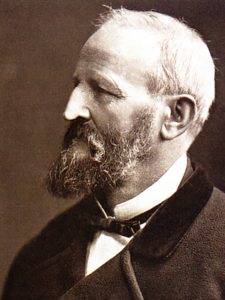

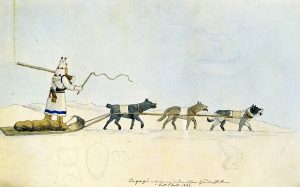

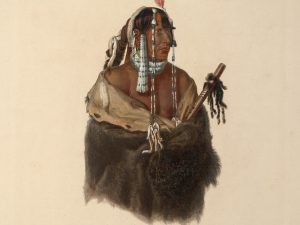

Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) was a Swiss artist best known for his participation in Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied's Missouri River Expedition (1832-1834) and his arresting paintings and portraits of Native Americans. The illustrations by Bodmer are an invaluable 19th-century ethnographic record of Native American life and tradition before mass settlement.

Missouri River Expedition of 1832 – 1834

Here in Europe, I have acquaintances; in America, I had friends.

Later Years & Artistic Legacy

These images have the sharpness and selectivity of medical drawings that capture anatomical or surgical conditions: Here the pencil enables clarity, emphasis and separation of parts and levels that the camera lens is unable to achieve.

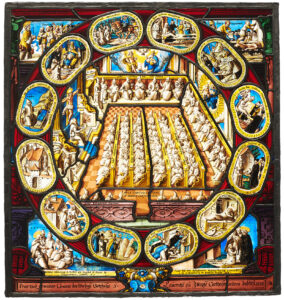

Bodmer's illustrations can be found in many cultural institutions, including the North American Native Museum NONAM in Zurich, Switzerland, The Whitney Gallery of Western Art in Cody, Wyoming (USA), the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska (USA), the Newberry Library of Chicago (USA), and the German Leather Museum in Offenbach, Germany.

Video on an exhibition on Karl Bodmer at the MET. Metropolitain Museum of Art / YouTube