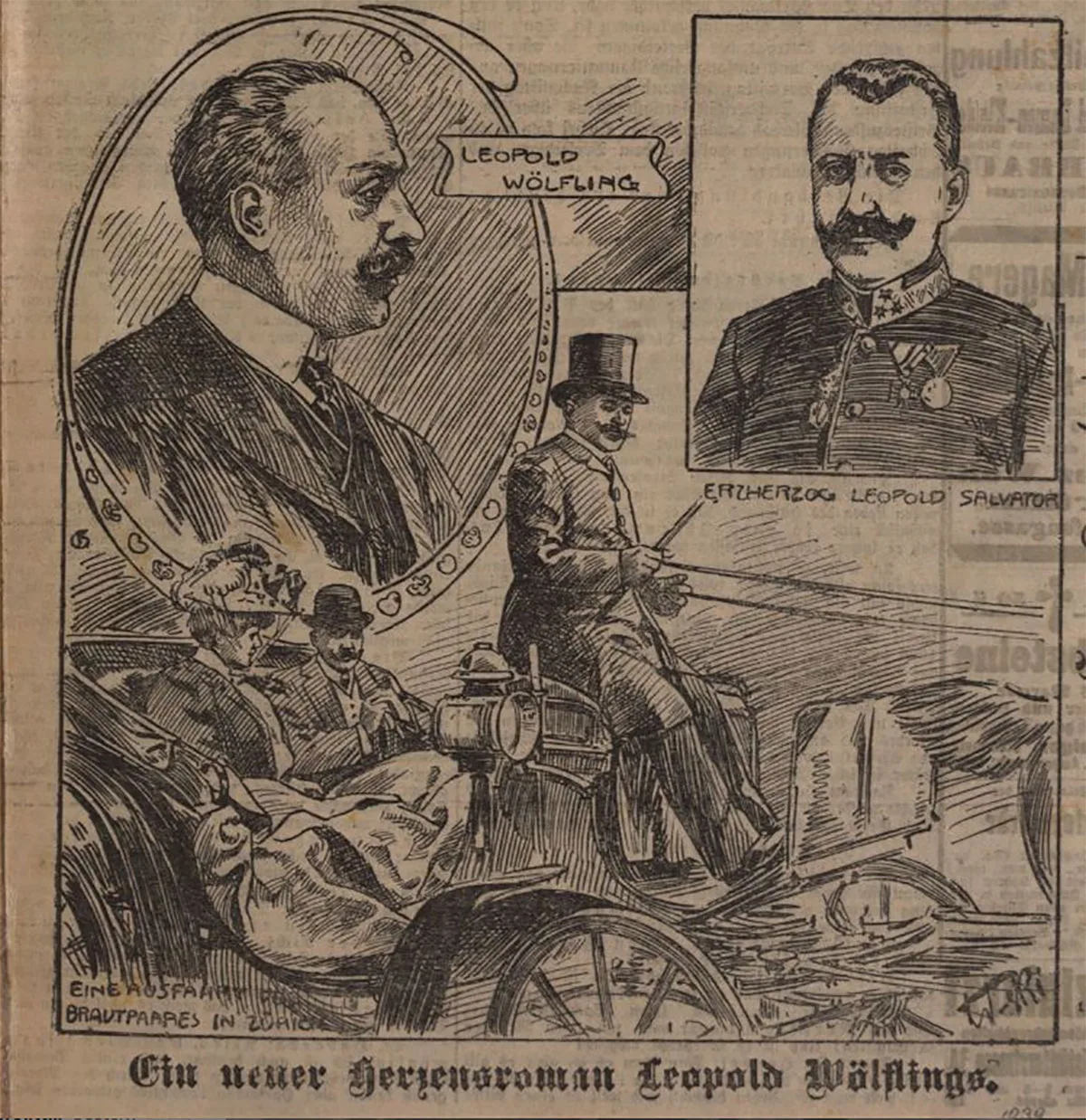

Leopold and the women

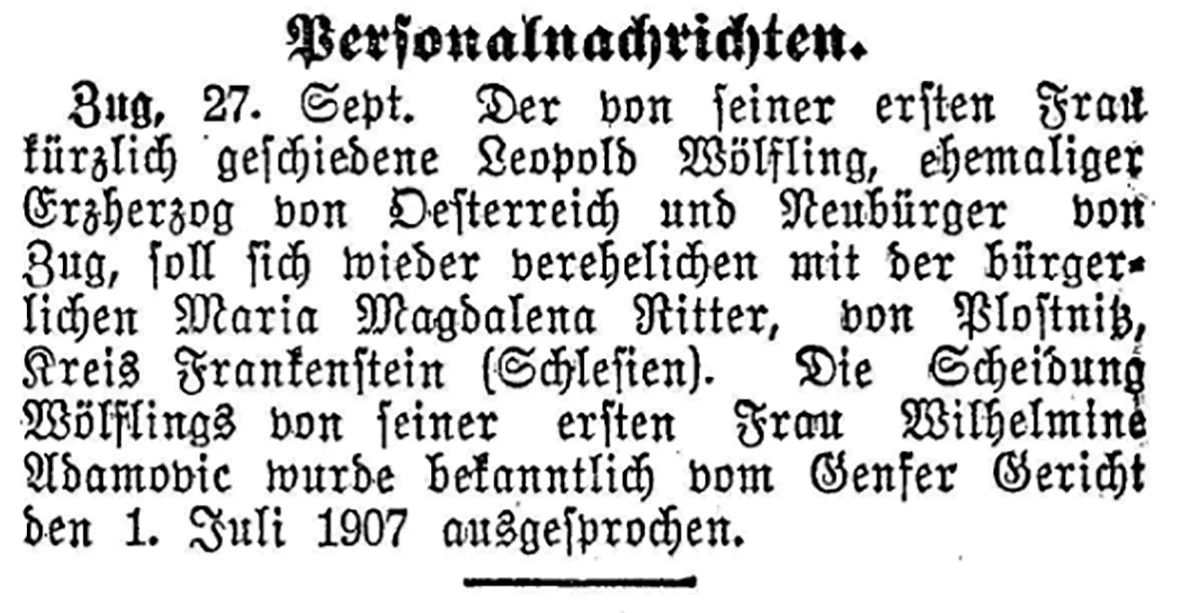

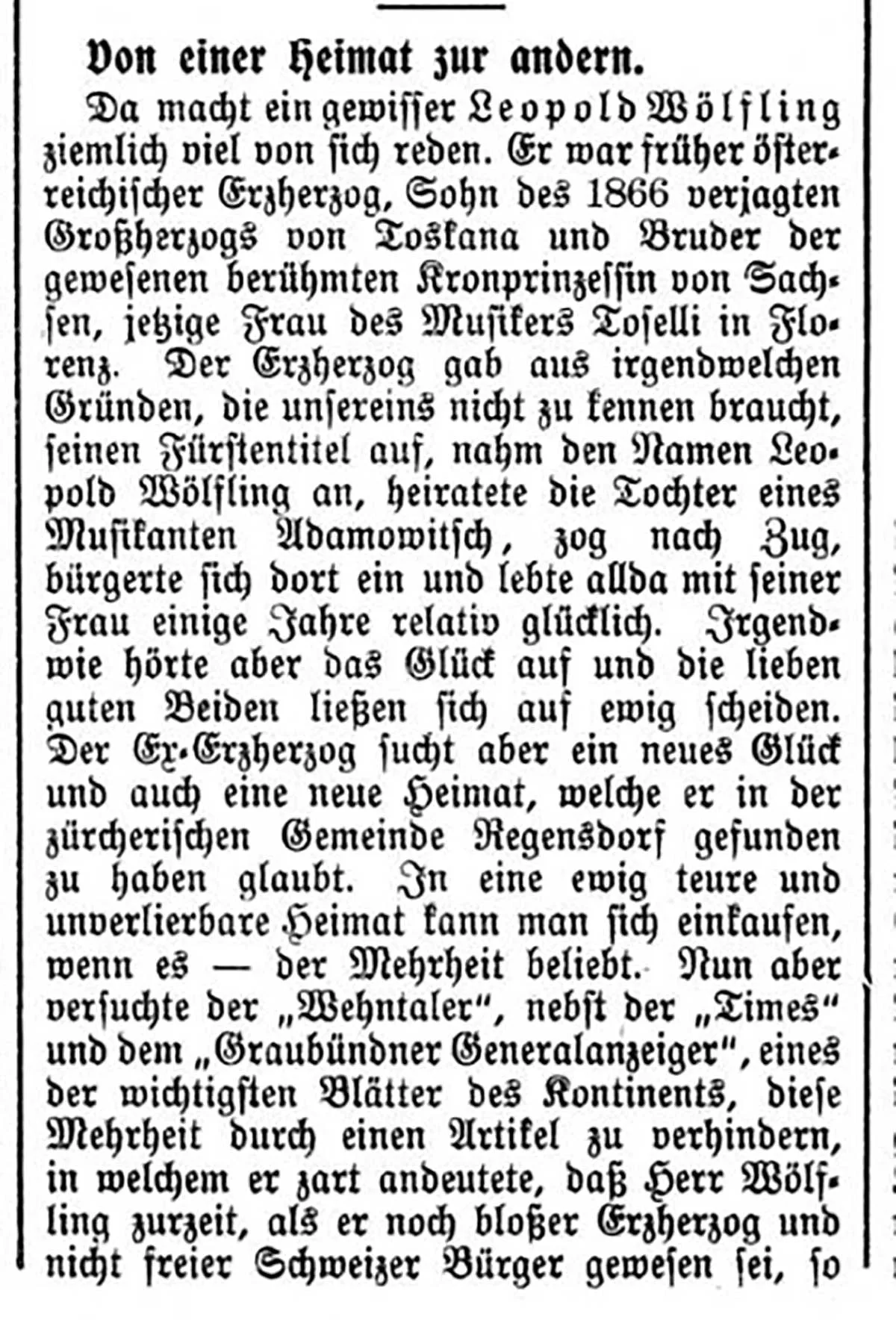

Leopold Wölfling remarried, and his bride was once again a lady with a dubious reputation. And his naturalisation became problematic. His sister Louise, now also living in Switzerland, was presented with an opportunity to take revenge on the royal house of Saxony...

An unexpected visit for Louise

Louise and Leopold

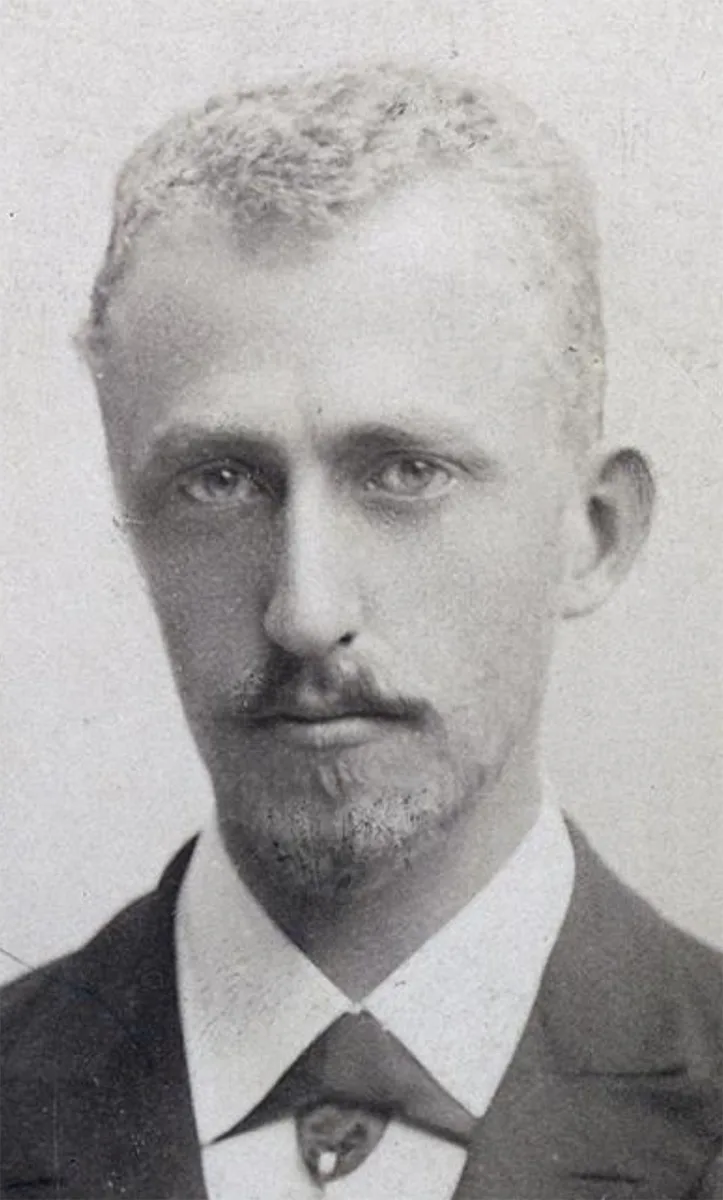

In 1902, Crown Princess Louise and Archduke Leopold of Austria-Tuscany fled to Switzerland. The siblings sought to escape from their straitjacketed life in the bosom of the Habsburg family. They succeeded, but their lives became a scandal-plagued descent into a normal middle-class existence, and ultimately ended in poverty and loneliness.

Part 1: Escape to Switzerland

Part 2: The scandal becomes public knowledge

Part 3: The Archduke becomes a Swiss citizen

Part 4: Leopold and the women

Part 5: Regensdorf versus the Archduke

Read the detailed account of Louise and Leopold’s journey in the book of the same name, by Michael van Orsouw. It is published by Hier und Jetzt.