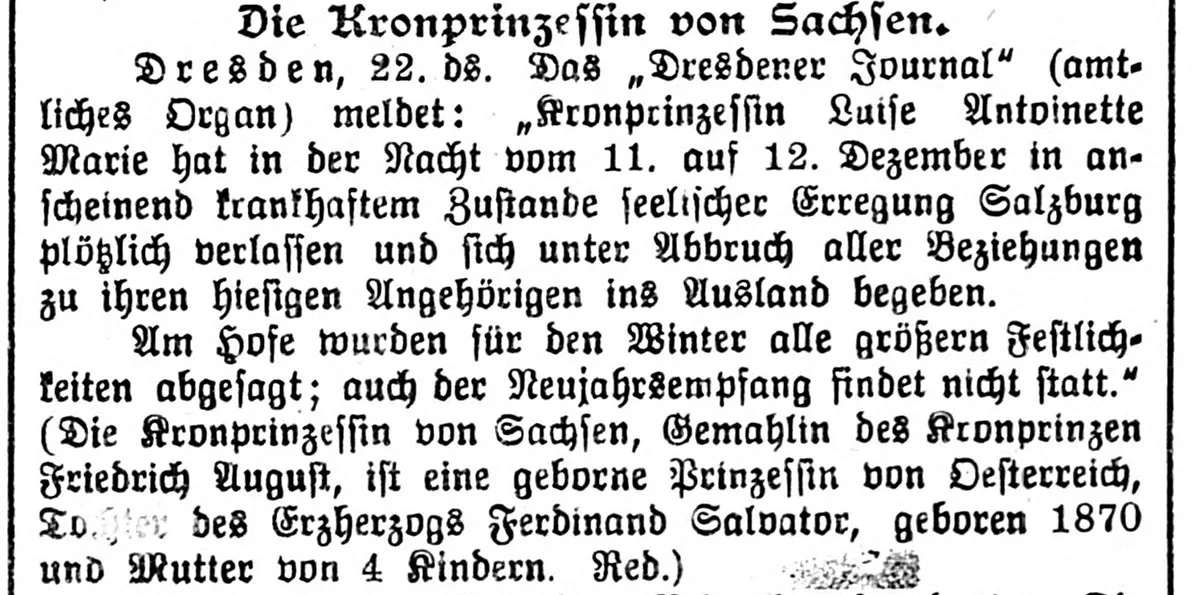

The scandal becomes public knowledge

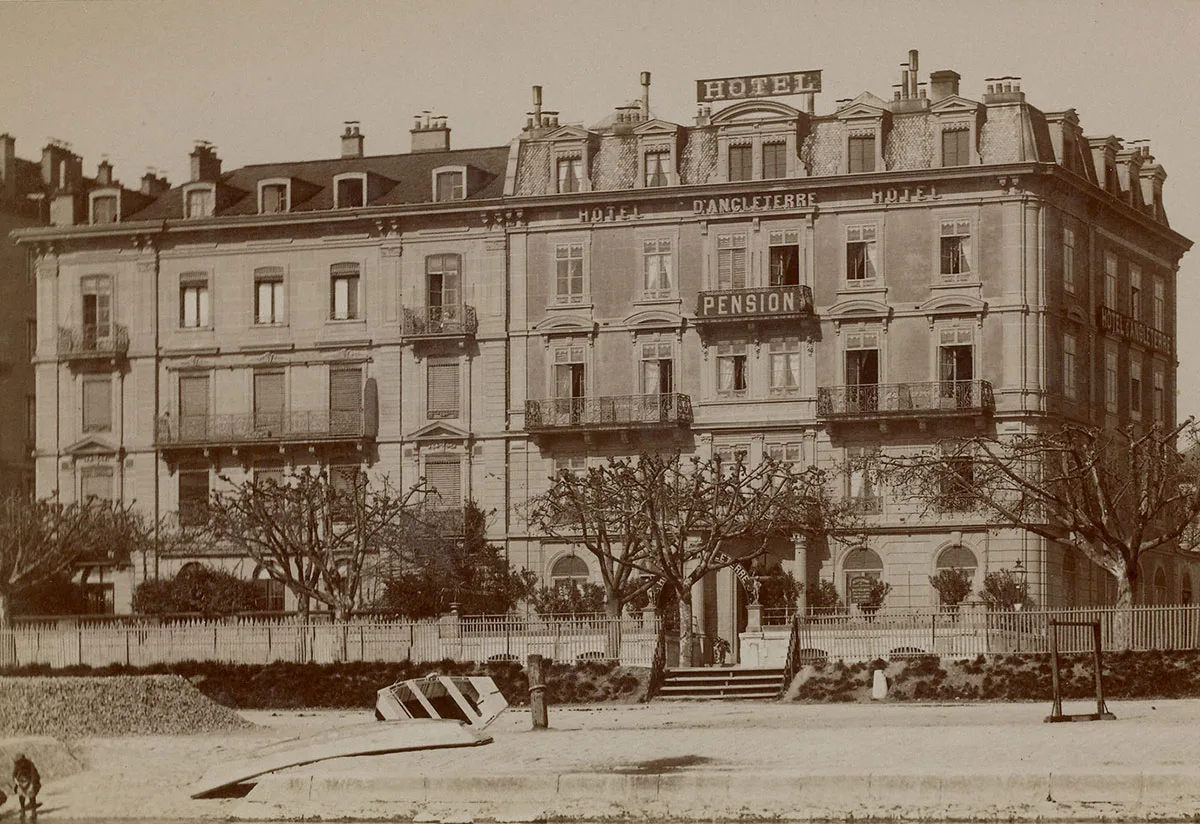

In Switzerland, the runaway Habsburgs Louise and Leopold deliberately laid false trails in order to continue hiding their whereabouts. But their efforts were unsuccessful, and the scandal shocked the aristocracy and the public throughout Europe.

A public relations masterstroke

Louise’s tragic life in pictures… YouTube

Louise and Leopold

In 1902, Crown Princess Louise and Archduke Leopold of Austria-Tuscany fled to Switzerland. The siblings sought to escape from their straitjacketed life in the bosom of the Habsburg family. They succeeded, but their lives became a scandal-plagued descent into a normal middle-class existence, and ultimately ended in poverty and loneliness.

Part 1: Escape to Switzerland

Part 2: The scandal becomes public knowledge

Part 3: The Archduke becomes a Swiss citizen

Part 4: Leopold and the women

Part 5: Regensdorf versus the Archduke

Read the detailed account of Louise and Leopold’s journey in the book of the same name, by Michael van Orsouw. It is published by Hier und Jetzt.