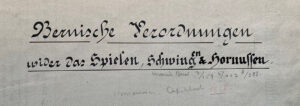

Hornussen – the “invention” of a national sport

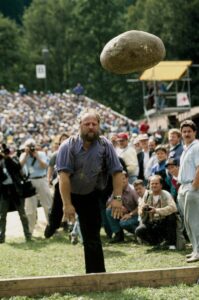

Along with Schwingen and Steinstossen, Hornussen is one of Switzerland’s national sports. Many people think of Hornussen as an ancient and typically Swiss game. Hornussen is indeed very old, but it’s only since the 19th century that it’s been considered a Swiss national game.

The “national sport” of Hornussen is the perfect vehicle for bringing together, in one flag-waving patriotic package, the domains of sport and tradition, rivalry and cohesion, urban and rural. Dukas / RDB

Report on the sport of Hornussen. Trans World Sport

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch