Sport and politics — an (un)happy relationship?

This year’s hosting of the Winter Olympics and the Football World Cup by, respectively, China and Qatar – both authoritarian states – has sparked debate about the influence of politics in sport. A look at history shows that sport and politics have always gone hand in hand.

- ...sport always reflects societal ideas about the body, gender or origin. For example, the division into ‘typical’ men’s and women’s sports, such as football and rhythmic gymnastics respectively, can be traced back to biologistic notions and the corresponding understandings of gender roles from the 19th century. Over the past 50 years these ideas have been kicked out of some sports; the general socio-political struggles and developments have also had an impact in sport.

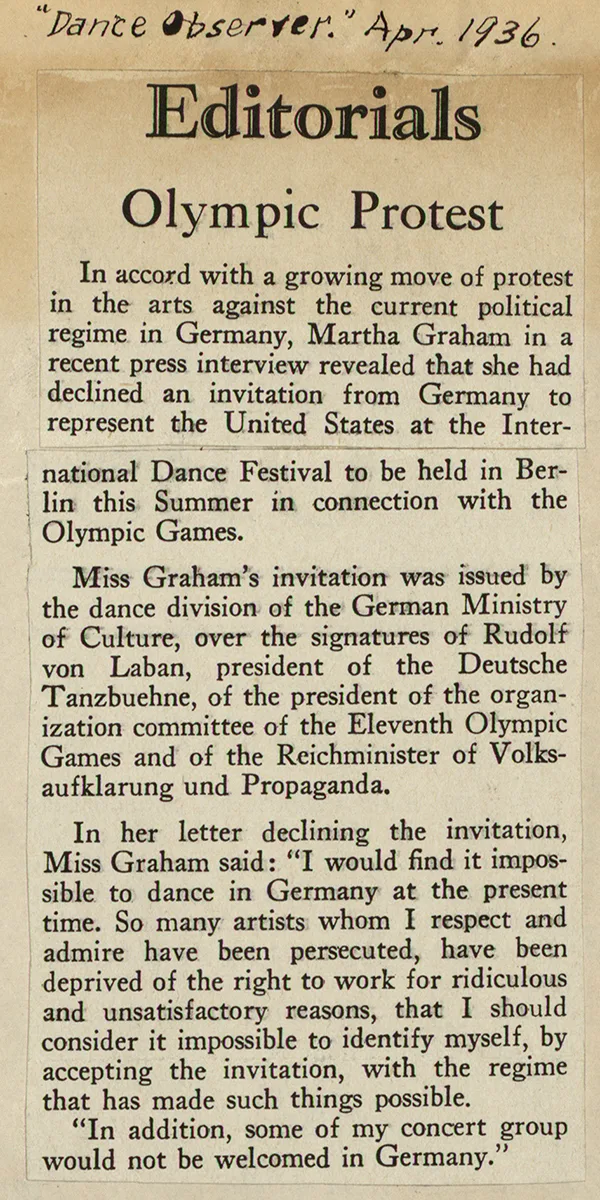

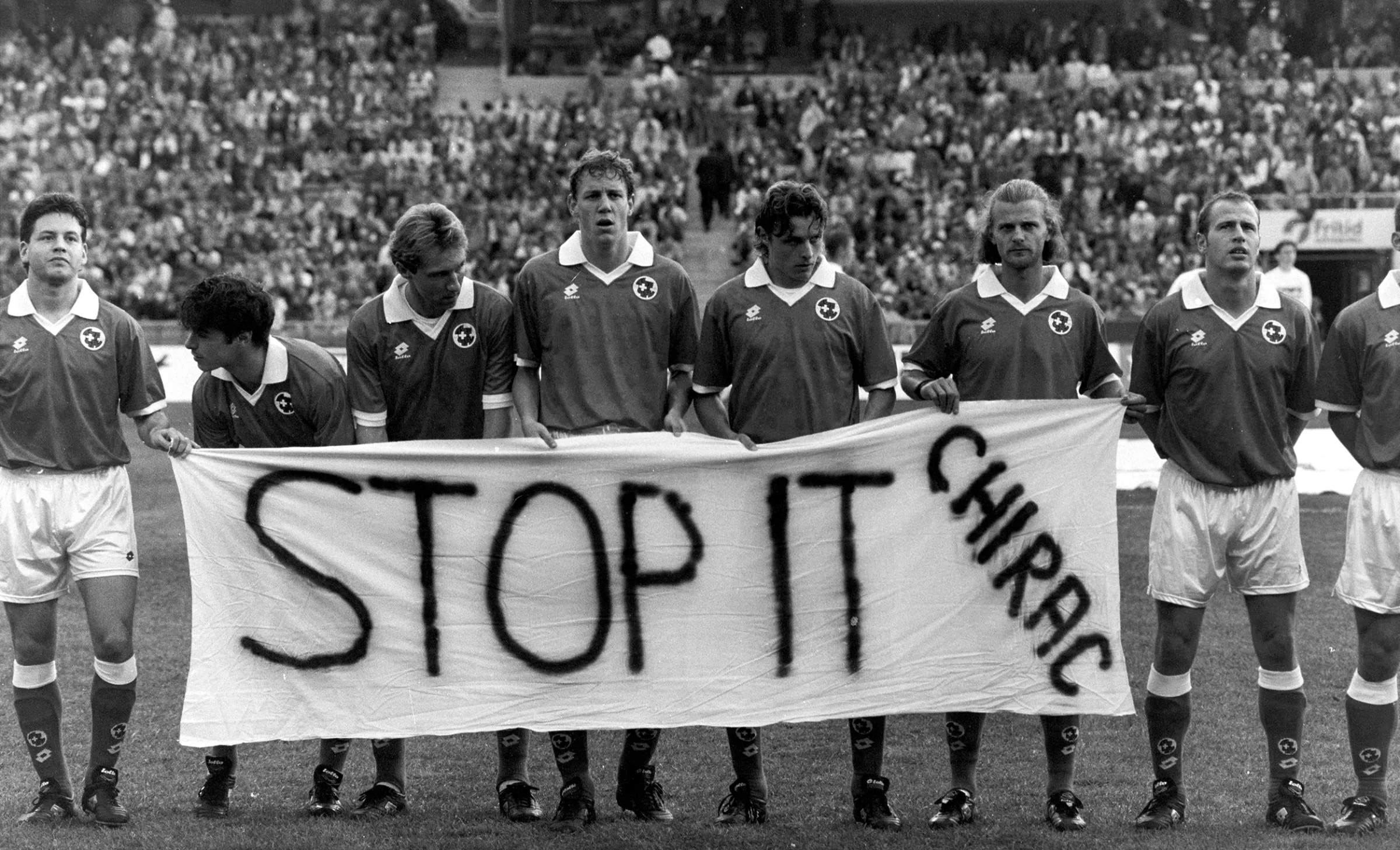

- ...due to the high level of spectator and media interest, sportsmen and women, but also politicians, use sport as a platform for their political messages.

- ...even the awarding of sports events to particular hosts is always a political issue. Awarding such events to authoritarian countries raises questions, especially in the western world, about human rights; in addition, candidates for award are sponsored and financially supported by politics.

- ...the admission to an international association of a territory that defines itself as a newly independent state can be read as a political statement if the status of that territory is contentious within the global community (see Kosovo and Taiwan).

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch