The Siege of Dijon 1513

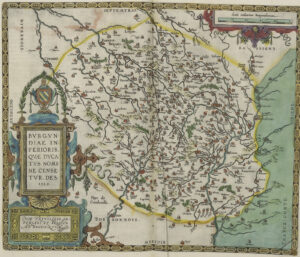

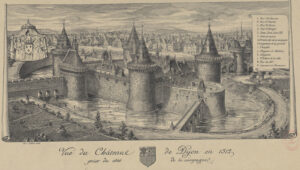

The Old Swiss Confederation won a stunning military victory over France at the Battle of Novara in June 1513. Following up on their successes in Italy, the Swiss and their Swabian allies successfully besieged the city of Dijon in September 1513, which marks the apex of Swiss power across Western Europe.

Burgundy, as dark with power as with wine…greedy, rich Flanders. These are the same lands in which the splendour of painting, sculpture, and music flower, and where the most violent code of revenge ruled and the most brutal barbarism spread among the aristocracy.

International Alliances and Coordinated Plans

They go forth of their country in great companies together, and whosoever lacketh soldiers, there they proffer their service for small wages. This is the only craft they have to get their living by. They maintain their life by seeking their death.

The Siege of Dijon

War is delightful to those who have had no experience of it.

Conflicting Legacies & An Exquisite Tapestry