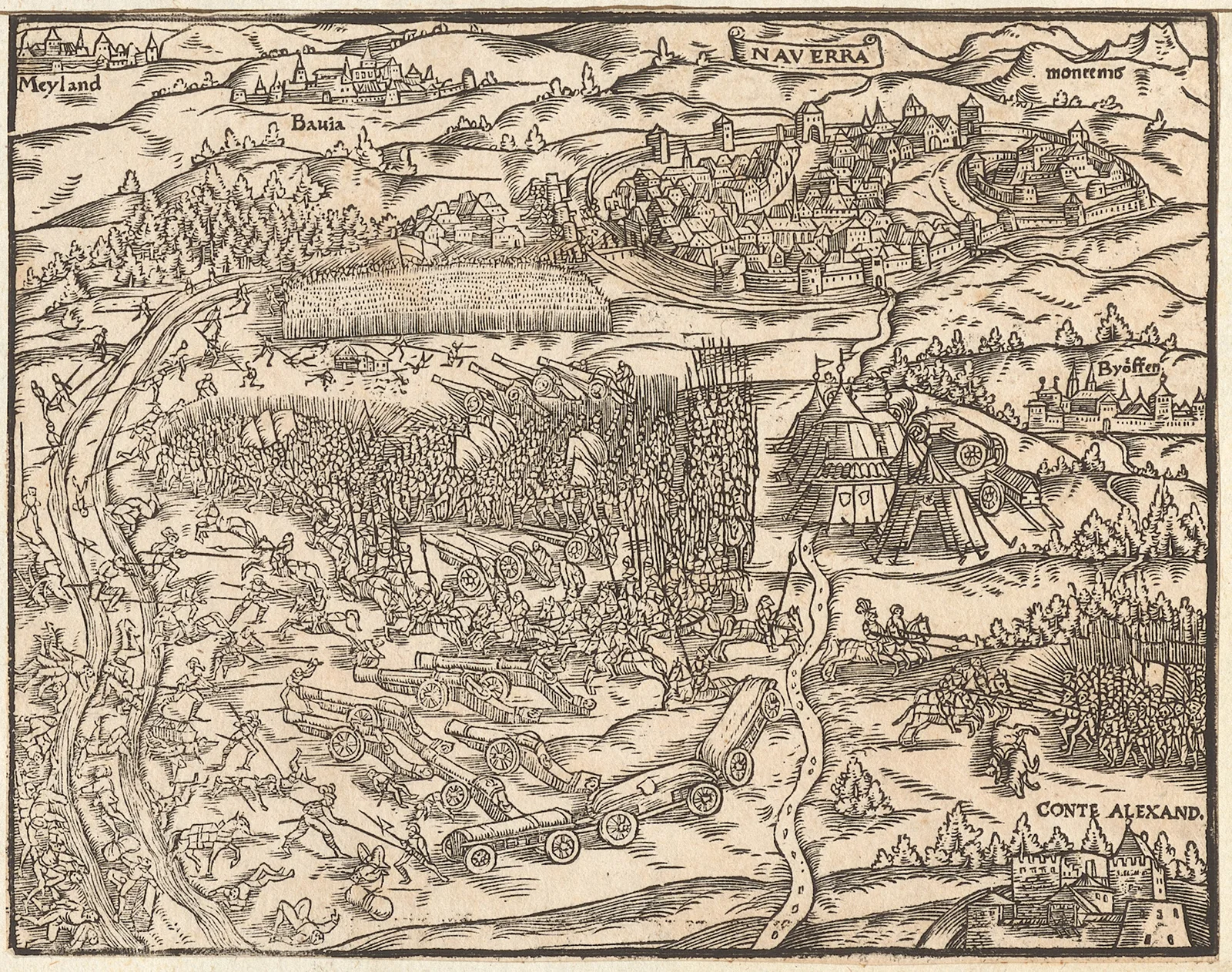

Zenith of Swiss Power: The Battle of Novara

The Battle of Novara on 6 June 1513 was the last great military victory of the Old Swiss Confederation and marked the peak of its power in Europe.

Rise and Fall of Franco-Swiss Relations

It is true that they are veritable soldiers and form the backbone of an army, but you must never be short of money if you want them, and they will never take promises in lieu of cash.

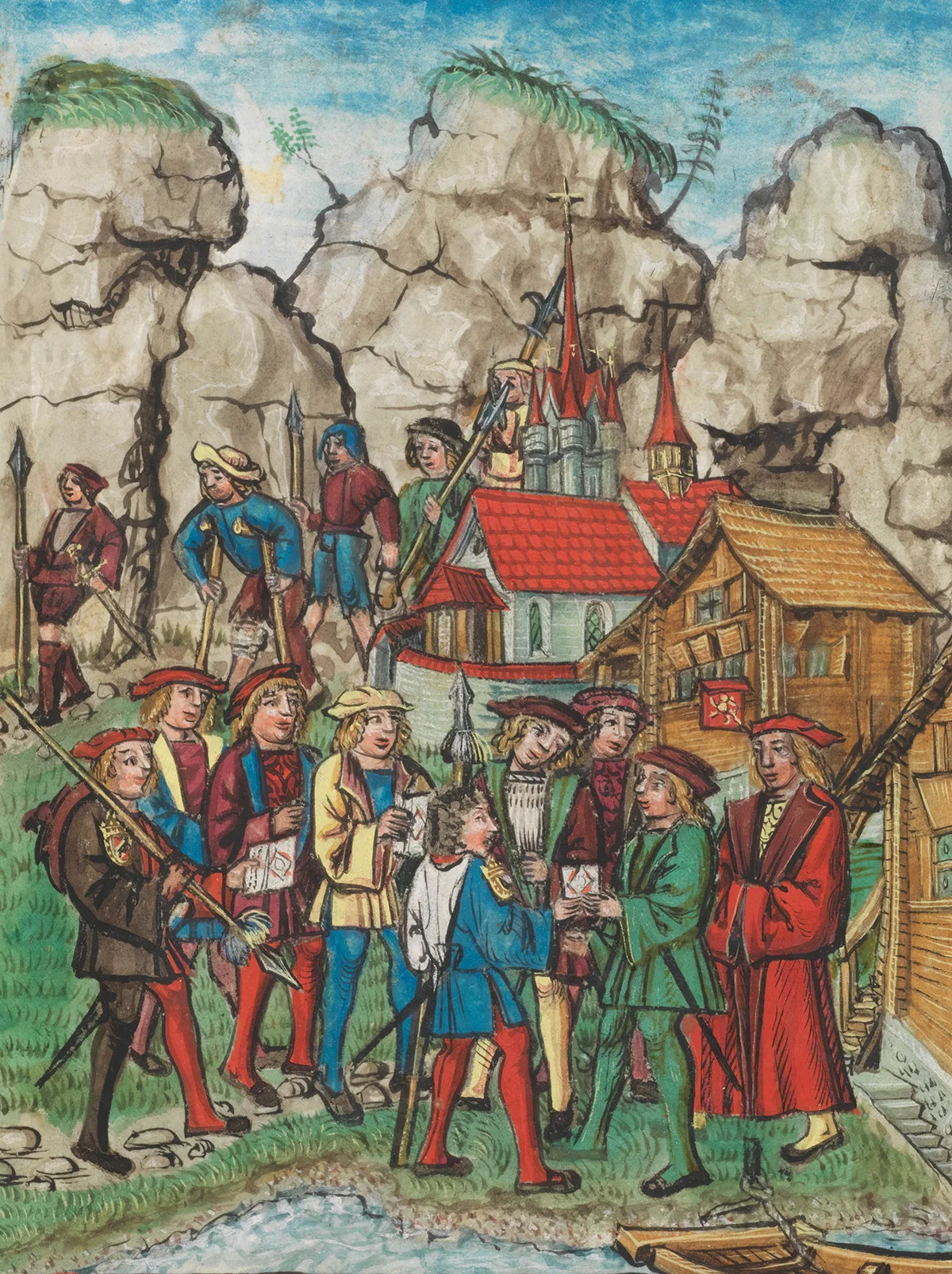

A Swiss-Papal Alliance

The smell of gunpowder is sweeter to me than all the perfumes of Arabia.

The Battle of Novara

The French have come to believe that without [the Swiss] they cannot win a battle. Because of this, the French are no match for the Swiss, and without Swiss help, no match for anyone else.

Novara’s Legacy & A Fascinating Woodcut

The unity and glory of their armies have made this savage, uncultured people famous.