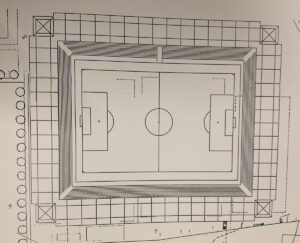

World Cup dreams made of steel pipes

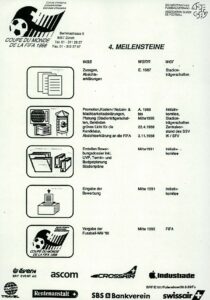

Little Switzerland had big dreams: our nation put in a bid to host the 1998 Football World Cup. It started with plans for gigantic stadiums, and ended with makeshift arrangements on village squares – and huge embarrassment.

The Swiss football stadiums of the 1954 World Cup. YouTube

Opening ceremony of the World Cup in Italy 1990. YouTube