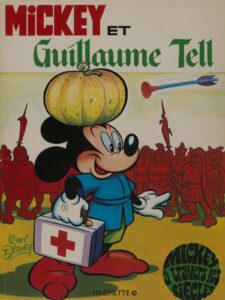

Mickey Mouse goes up in flames

Comics smoulder, books burn: in Aargau in 1965, mounds of so-called “trashy fiction” ended up on a fire. The campaign was called “Fight the trash", and it was intended to set the scene for further book burnings. But the scheme backfired.

The prototype campaign: “Kampf dem Schund”

The menace: Buffalo Bill and detective novels

The legal basis: between fighting trash, and freedom of the press

The burning: beginning of the end

The organisers’ initial delight at the presence of television crews quickly faded: the coverage of the event was “in a deliberately ironic tone” and the reporting didn’t present the positive aspects of the incineration campaign (in German). SRF