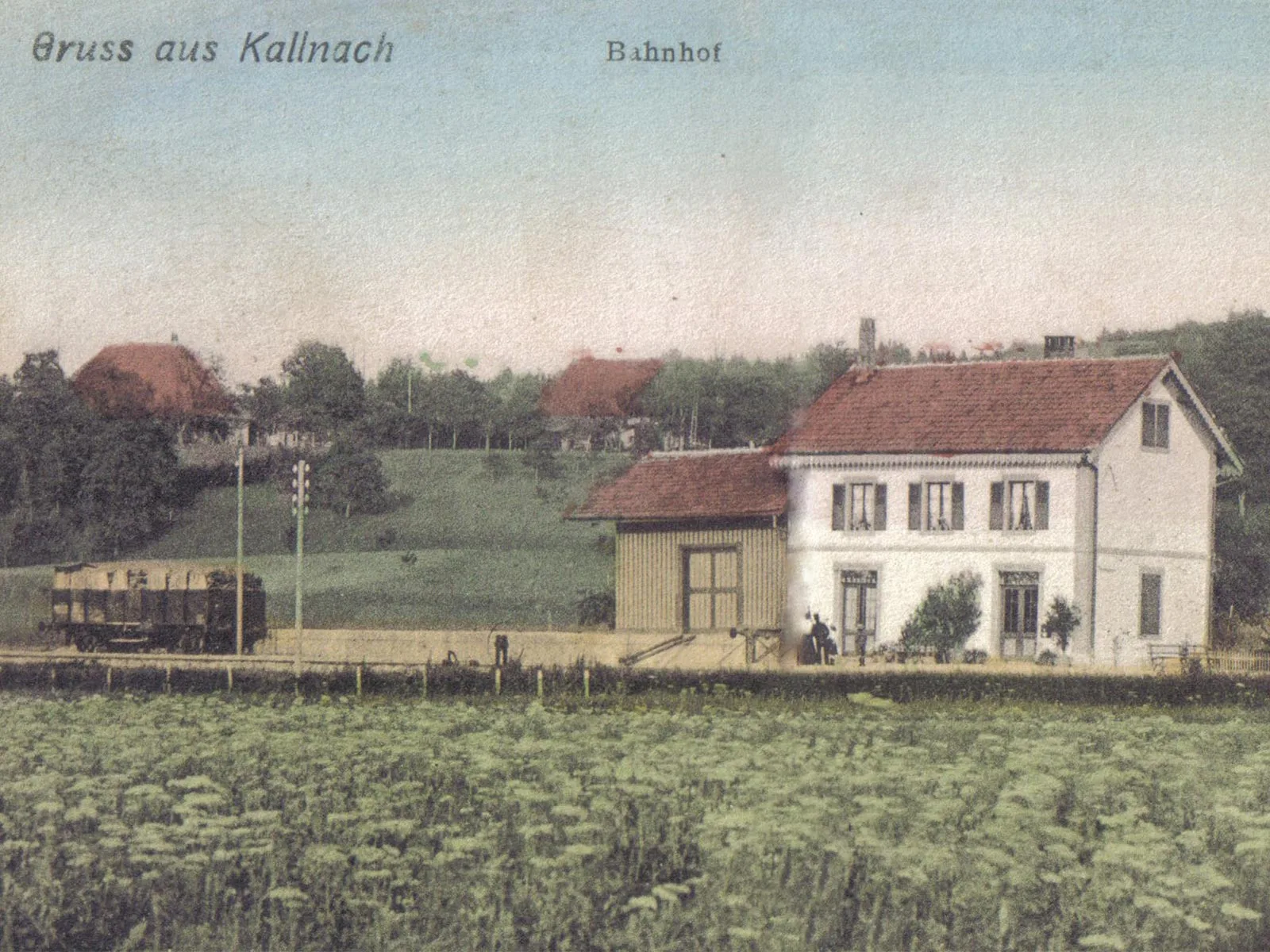

When bombs fell on Kallnach

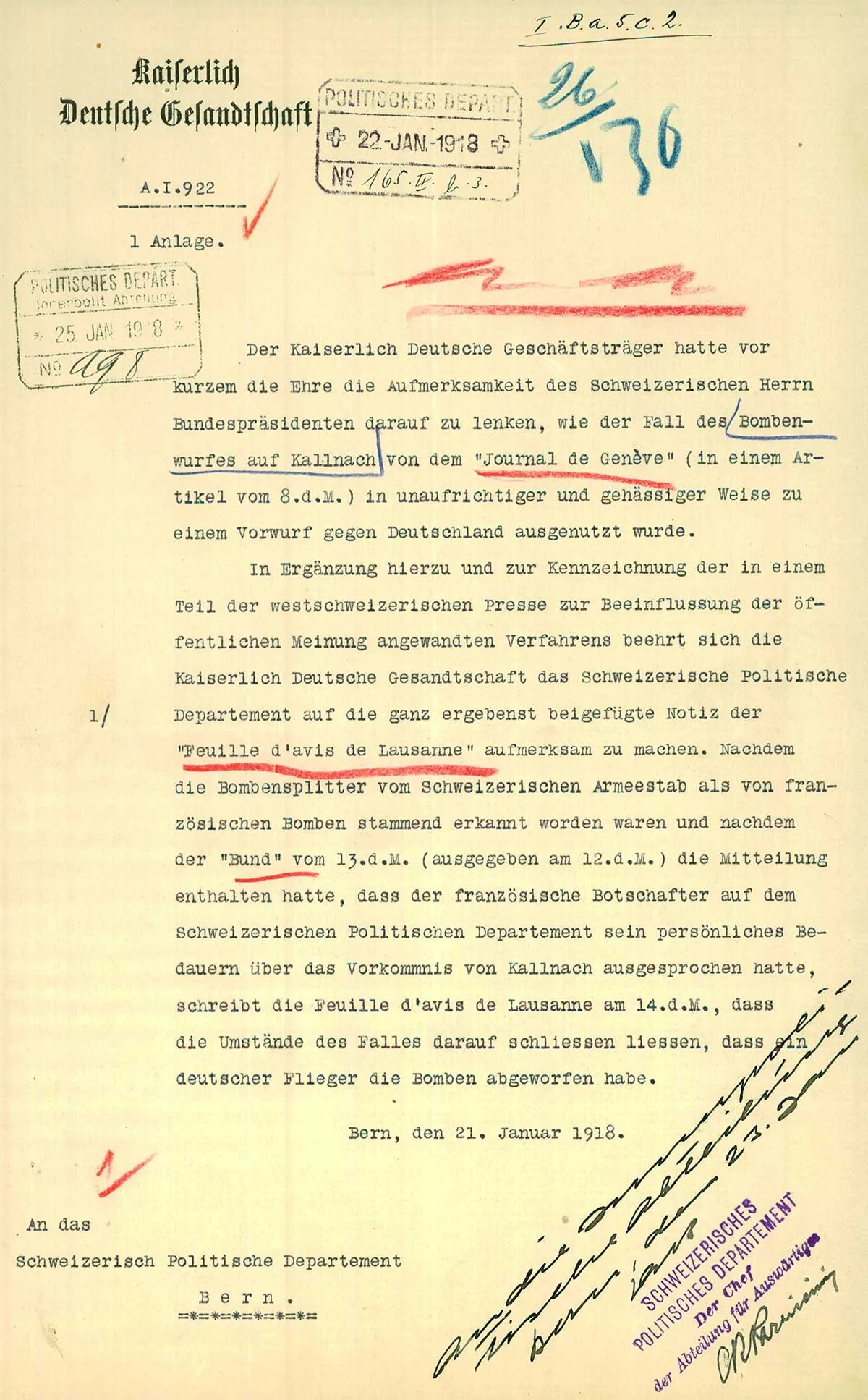

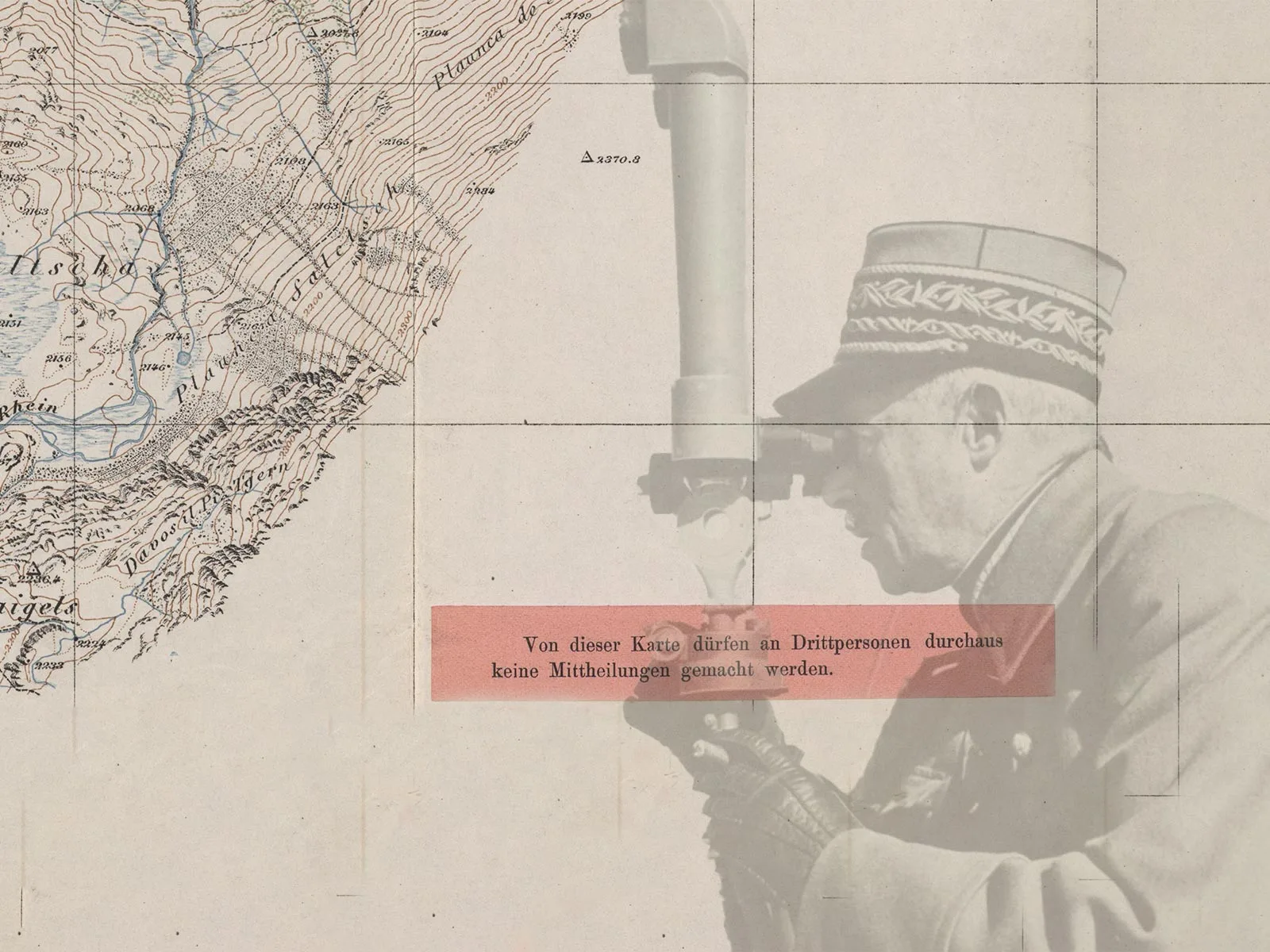

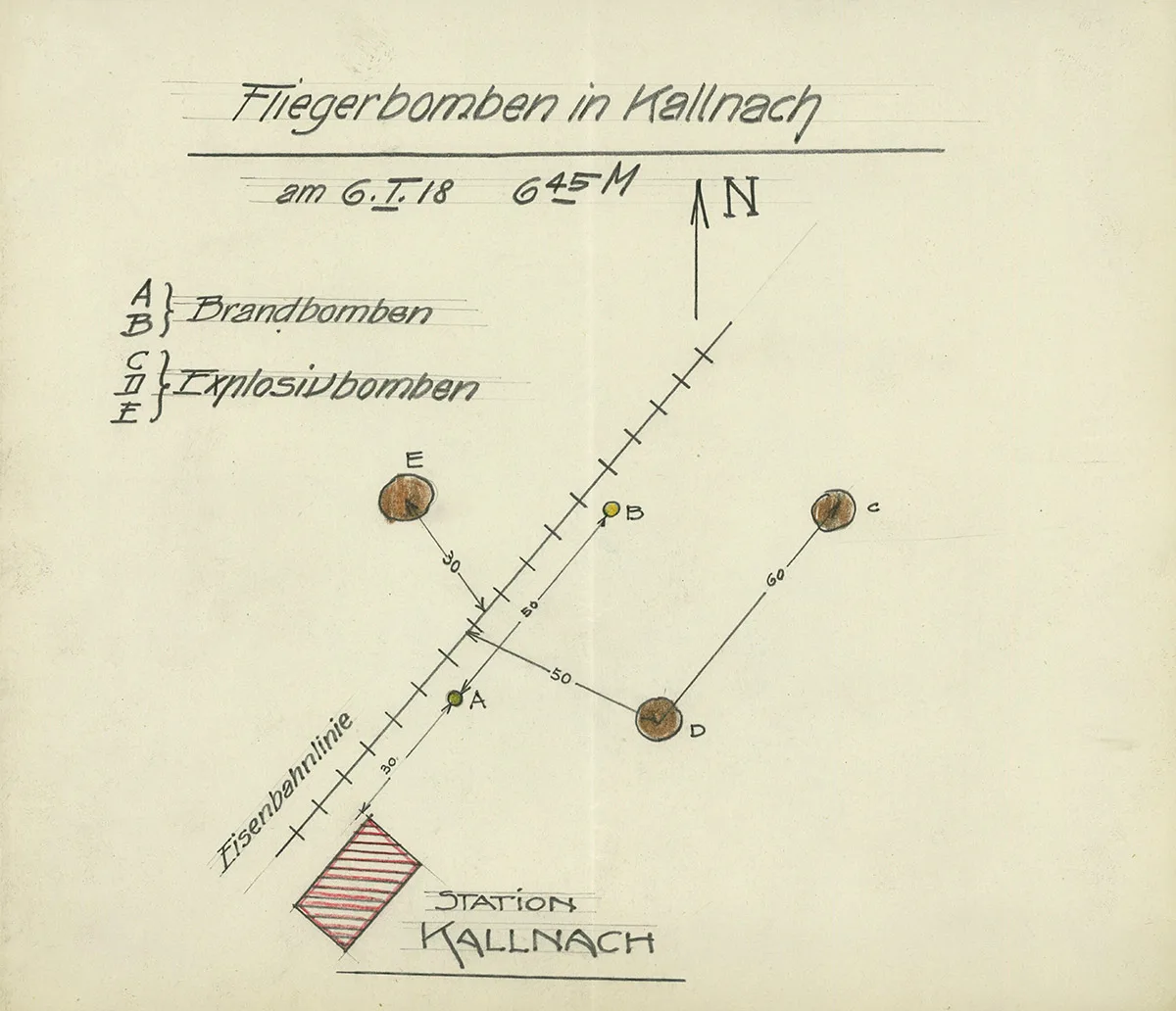

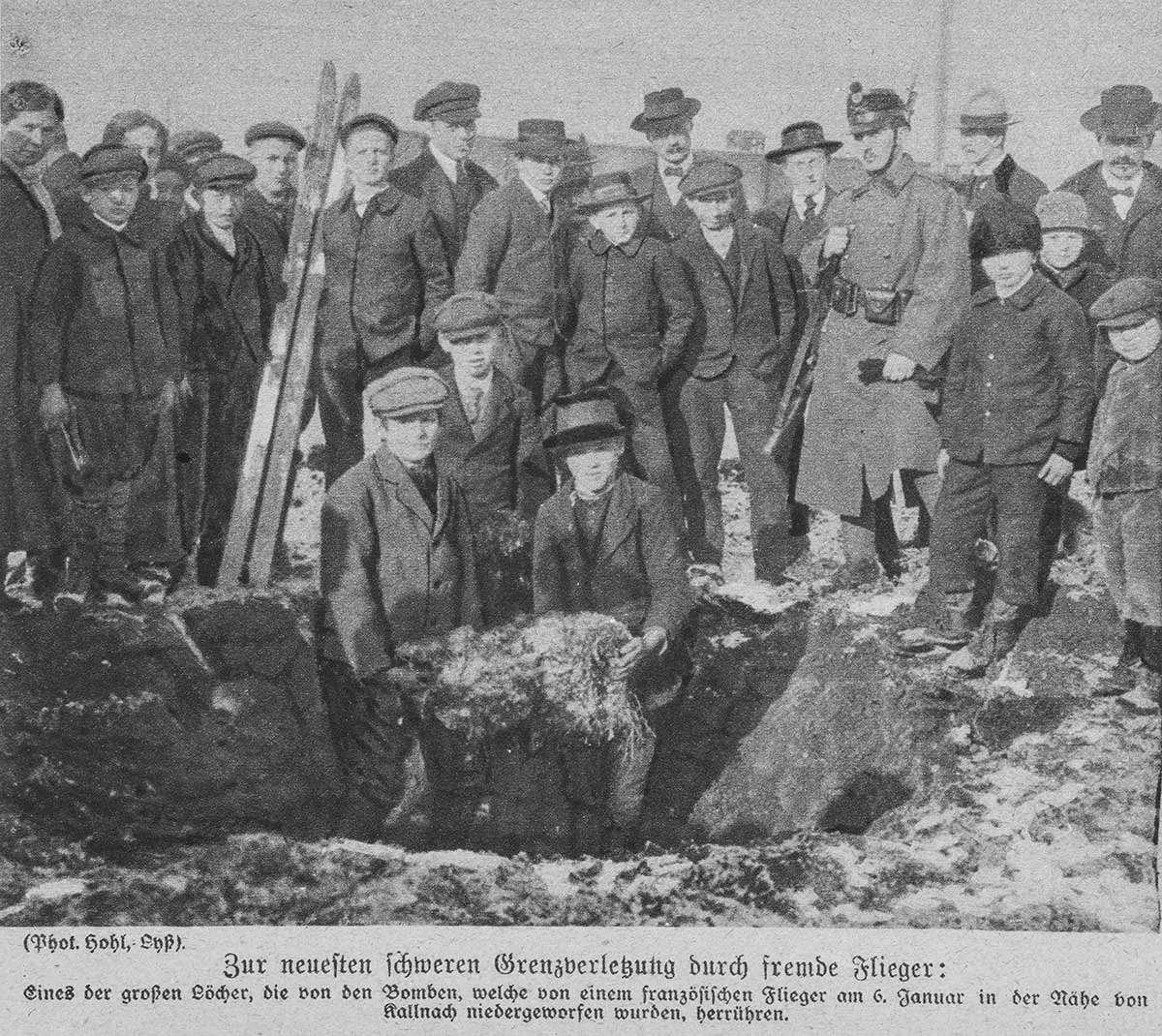

On 6 January 1918, five bombs were dropped near the station in Kallnach, sending shock waves through the ‘Grand Marais’ in Bern’s Seeland region. Fortunately, there was only some damage to property but no casualties. It quickly became clear that the bombs were French-made. But the question of who dropped them remains a mystery...

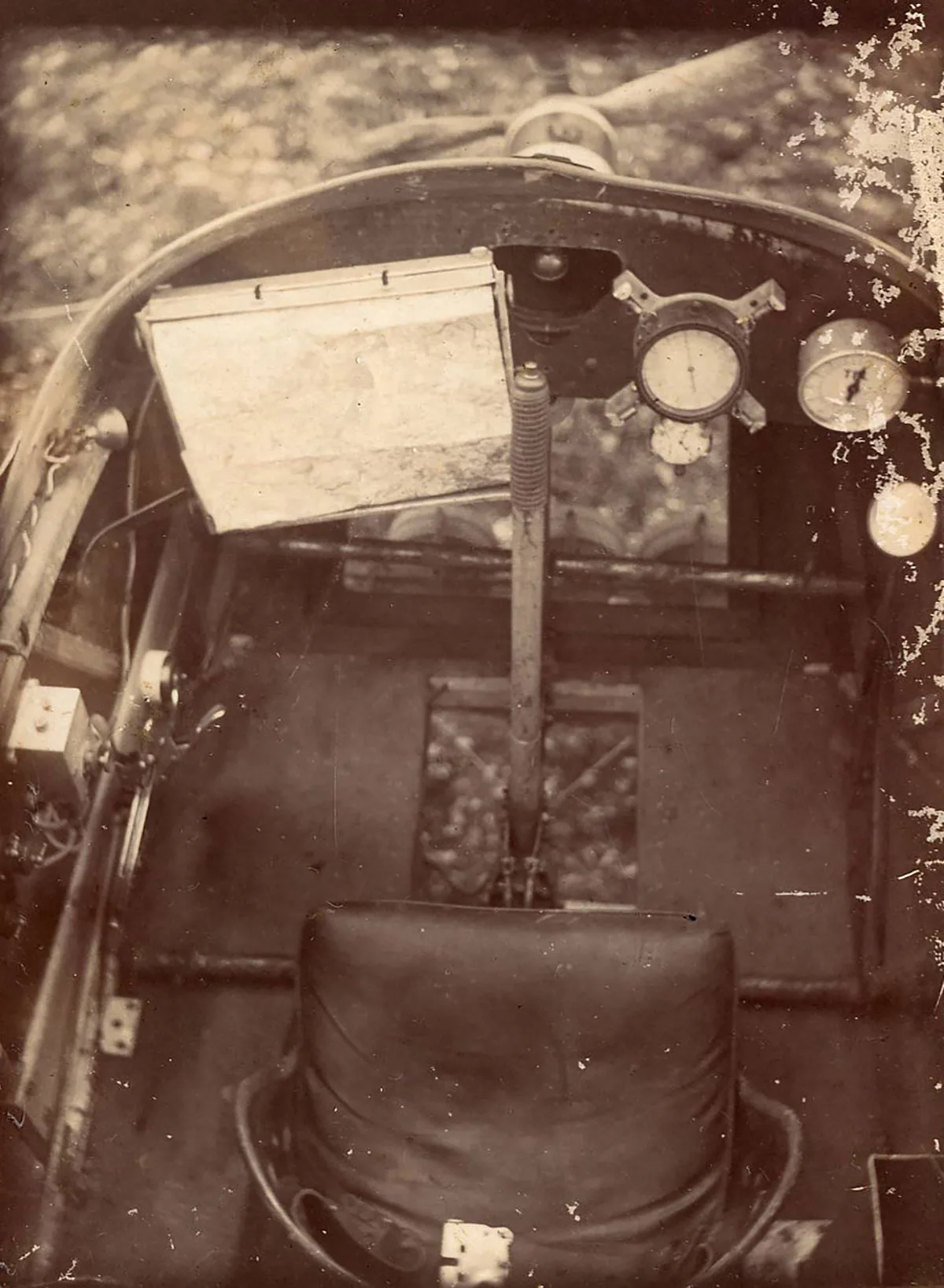

The French armed forces used Voisin aircraft in the First World War. YouTube