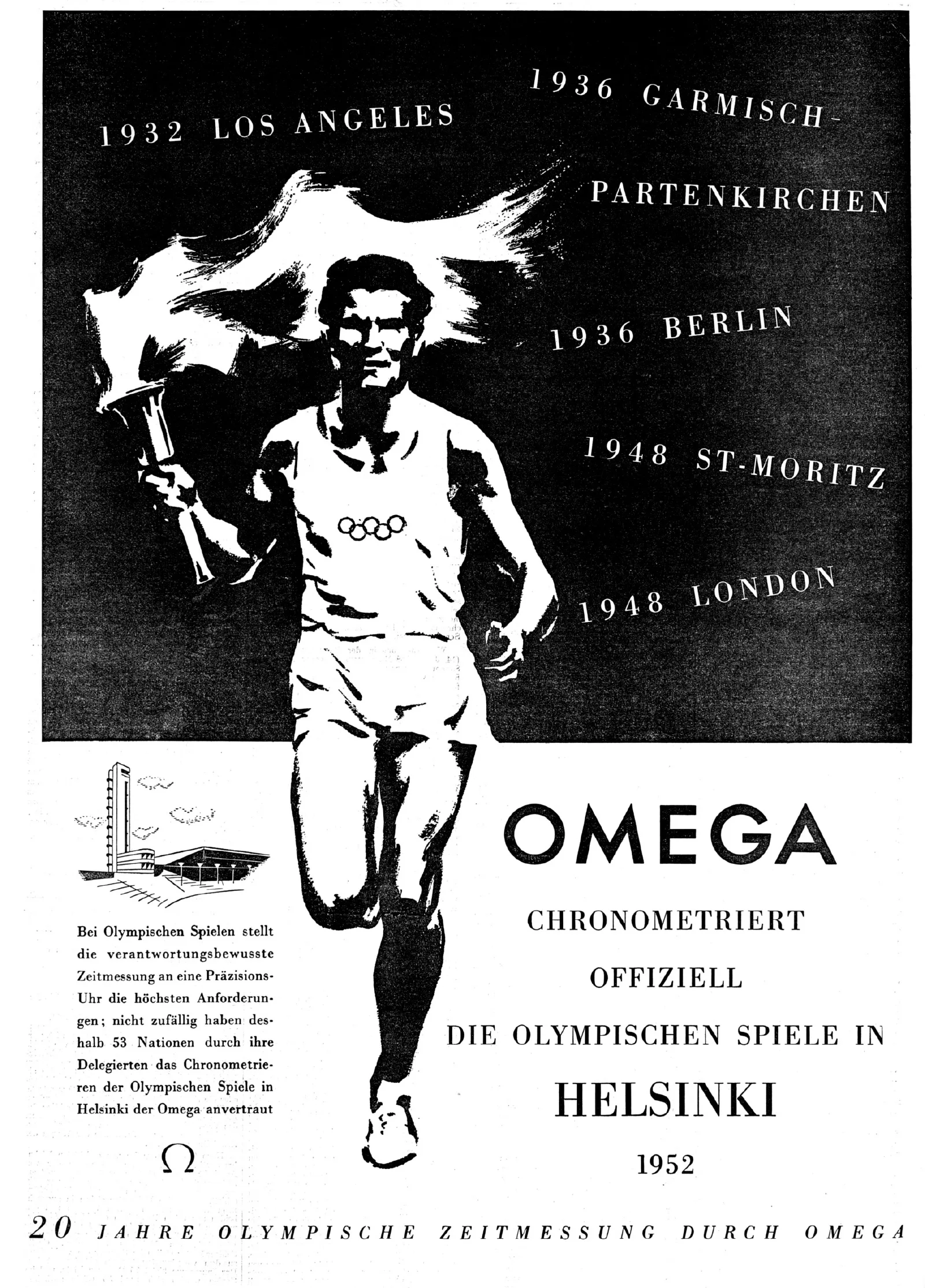

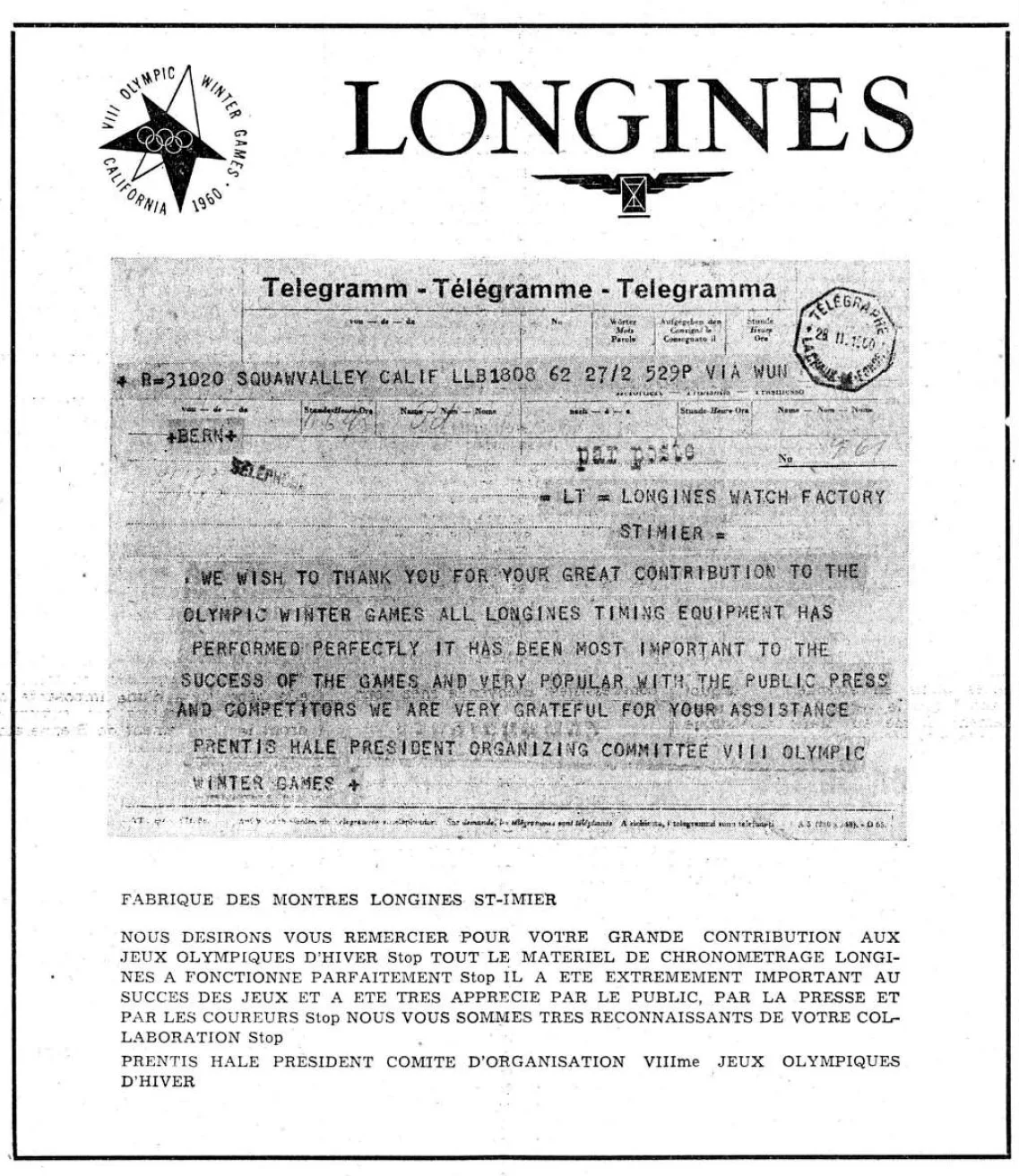

Swiss timekeepers at the Olympic Games

Timekeeping is hugely important in modern sport, which is increasingly competitive, professional and international. It has made remarkable progress since its early days. A look at the history of timekeeping at the Olympic Games, and the role of the Swiss watch industry and diplomacy.

Post-war innovation

Deploying diplomacy against the competition

Oemga explains athletics timekeeping technology in the Olympic Stadium at the 2012 Olympic Games in London. YouTube / Omega

Growing precision

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch

This article draws, among other sources, on the work of Swiss historians such as Pierre-Yves Donzé, Gianenrico Bernasconi, Marco Storni and Quentin Tonnerre, which examines topics such as timekeeping in sport, its diplomatic aspects, and competition between the Swiss and Japanese watchmaking industries.