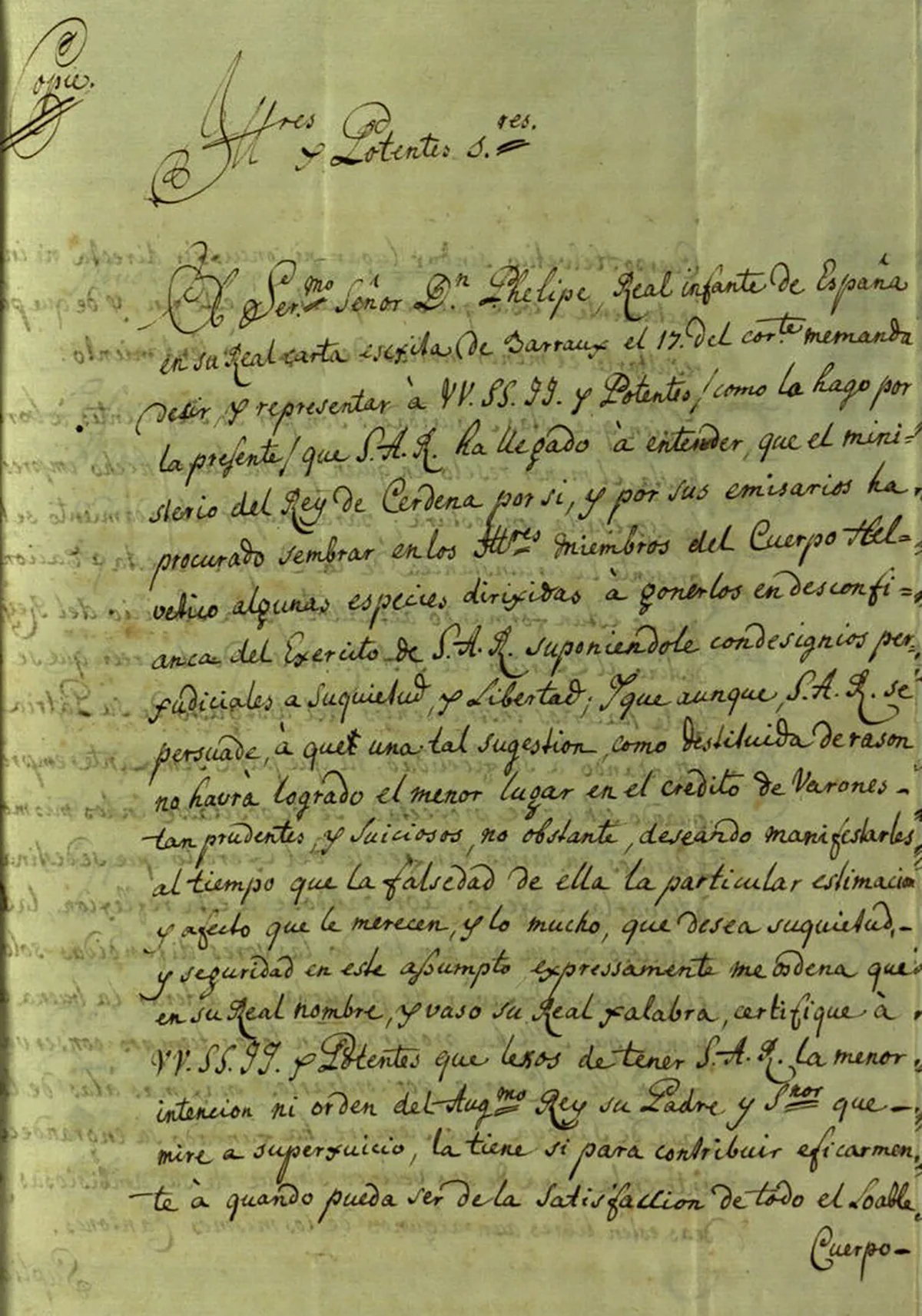

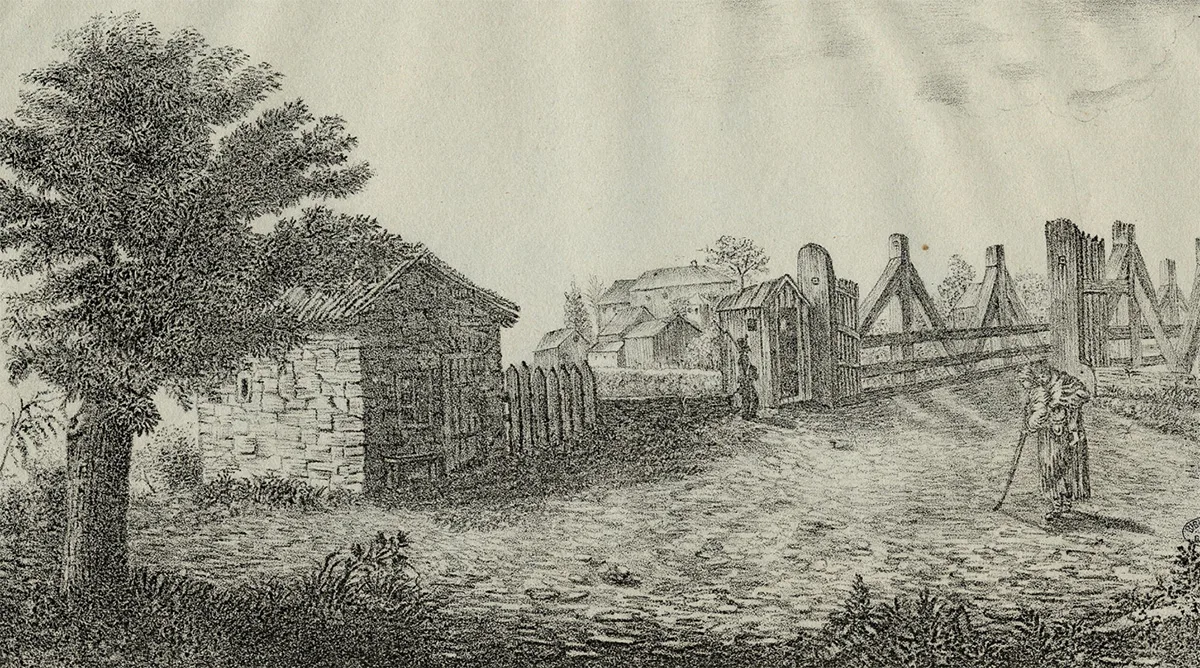

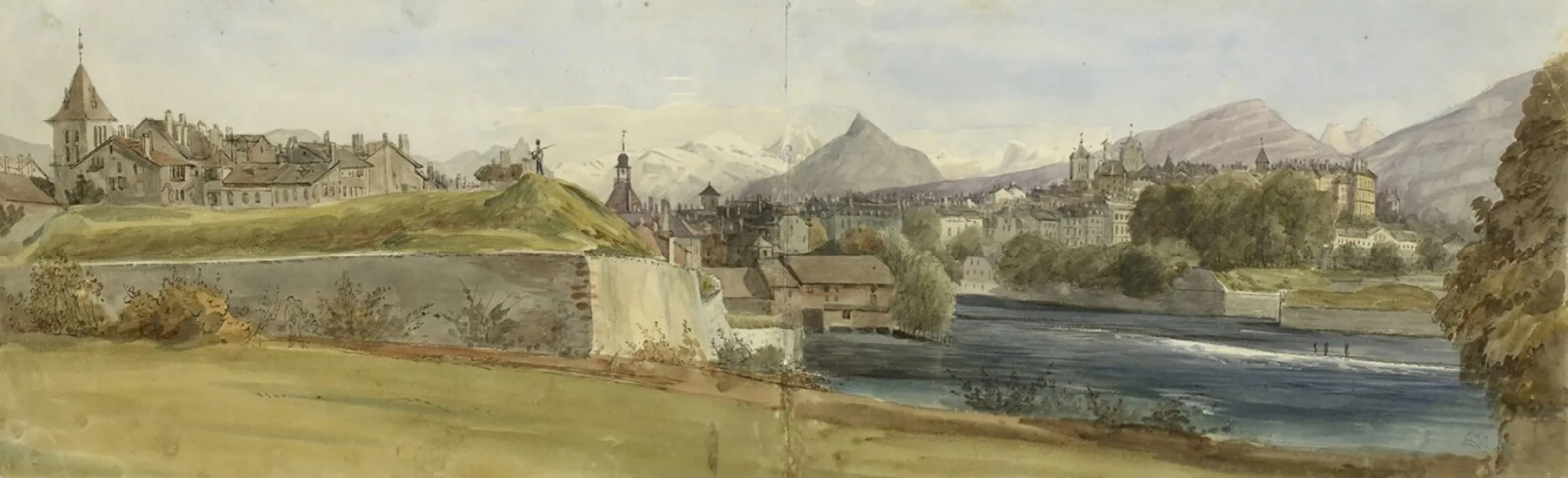

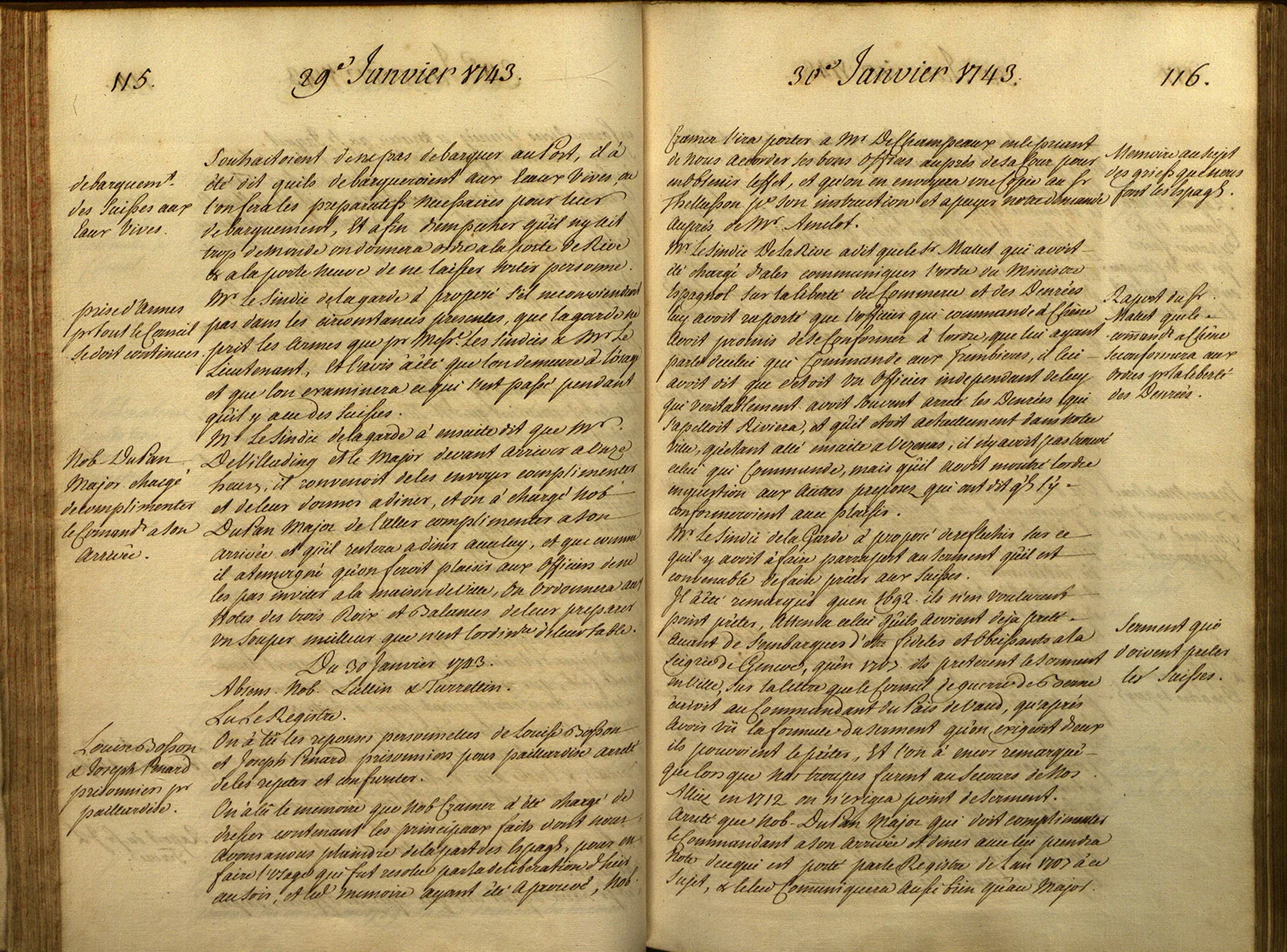

The encirclement of Geneva by Spanish troops in 1743

For almost seven years, from September 1742 to February 1749, Savoy villages neighbouring the city of Geneva were occupied and troubled by Spanish troops. Although part of the War of the Austrian Succession and therefore the great history of Europe, the occupation has been all but forgotten by historians.