How Swiss law is adopting European fundamental rights

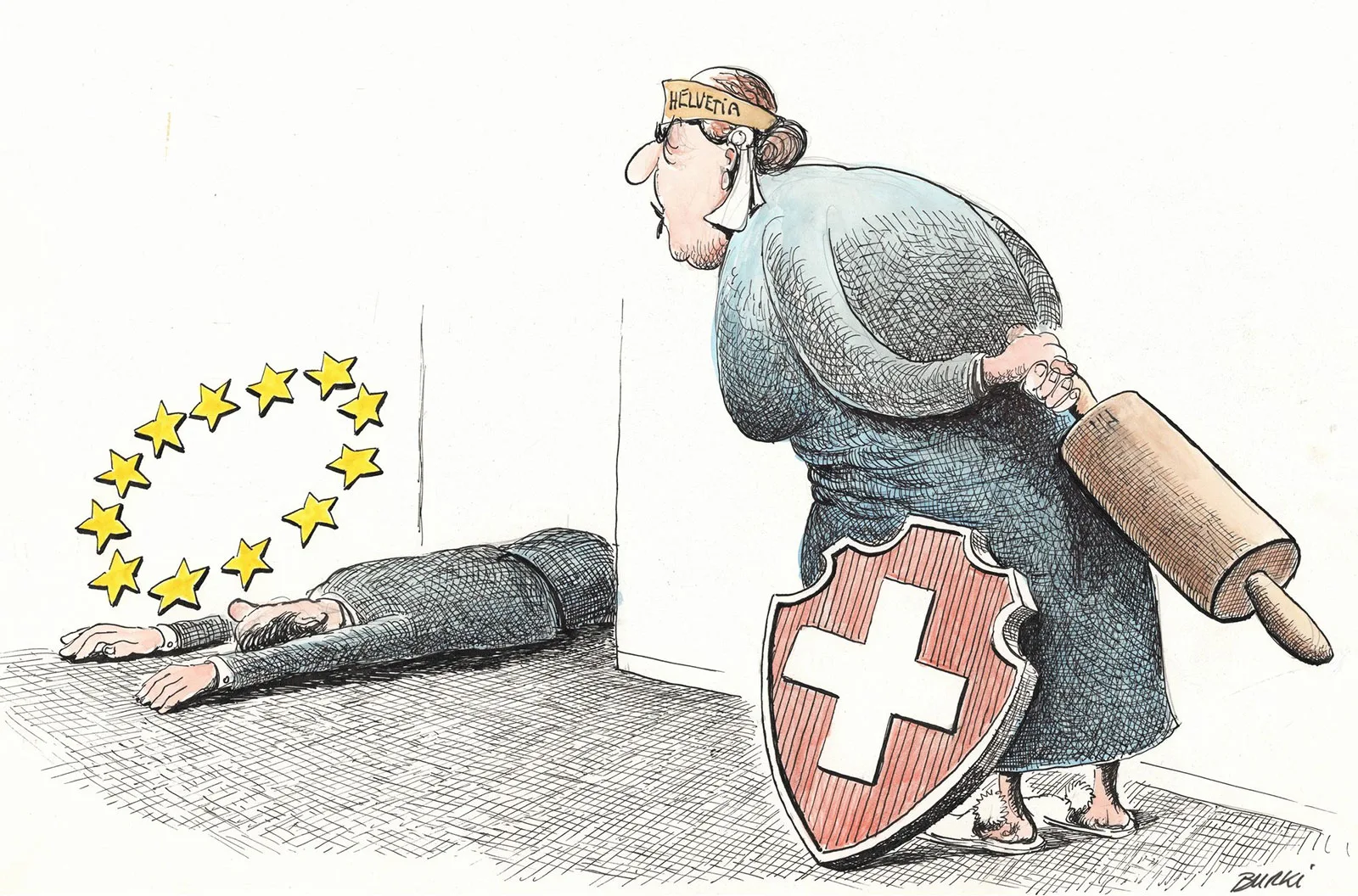

The Swiss Federal Constitution is caught in a push-and-pull between direct democracy, on the one hand, and European and international law, on the other. Certain European fundamental rights standards are being adopted nonetheless. The Council of Europe and the European Convention on Human Rights have had a marked effect on the current version of the Constitution. Decisions in Strasbourg continue to develop and enhance human rights standards that apply not just in the EU, but in Switzerland, too.

Constitutional balancing act

European fundamental rights standard

No word on the EU

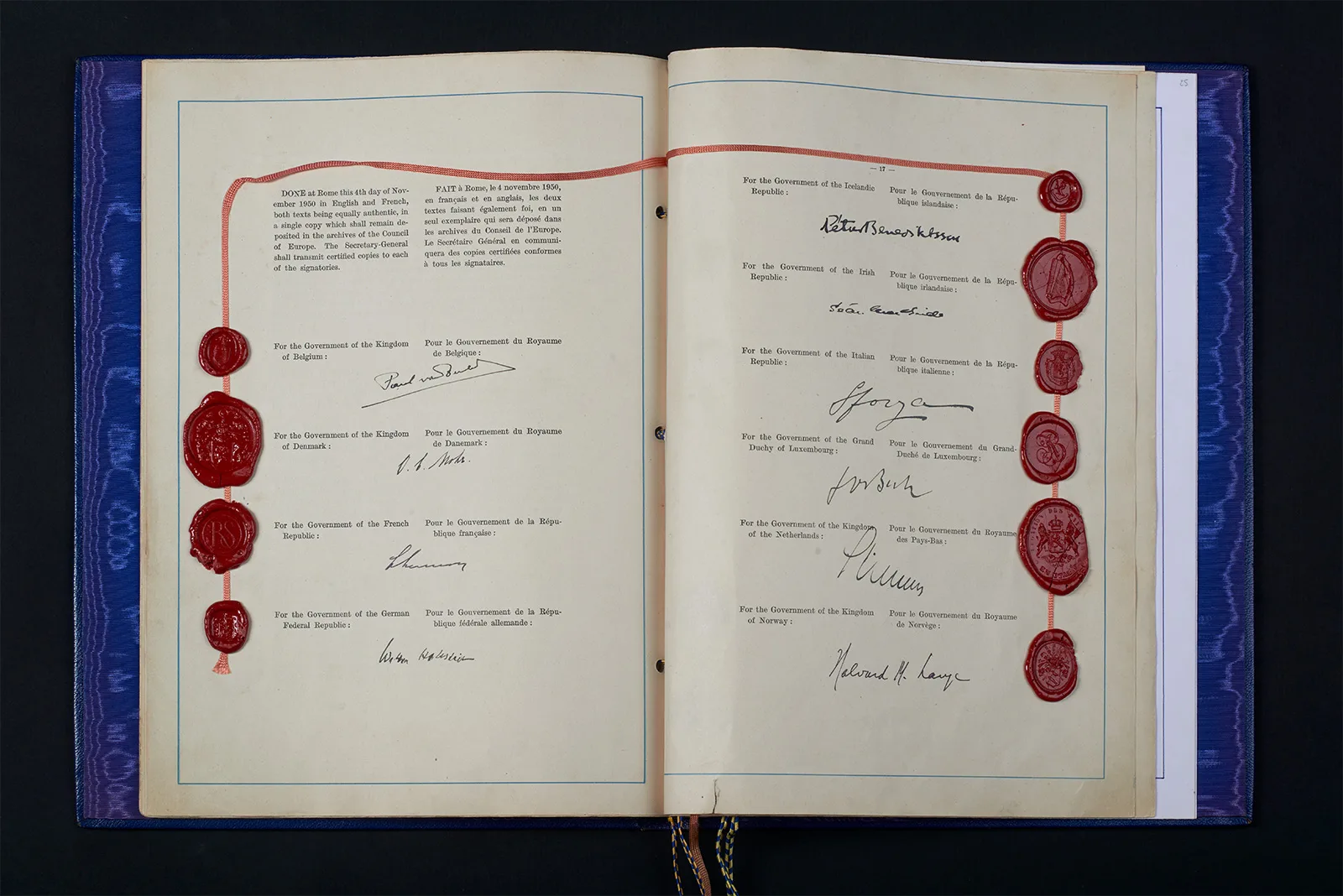

The Confederation and the Cantons shall respect international law.